Archive for December 22nd, 2023

NEW PAPER | Competition on the merits

What is competition on the merits? This is the question I seek to answer in my most recent paper, available here.

The notion of competition on the merits seemed irrelevant not so long ago (that is, before Servizio Elettrico Nazionale exposed a friction in the case law). Landmarks of the 2010s such as Post Danmark I, TeliaSonera or Intel went about applying Article 102 TFEU without paying much attention (if any) to this notion.

Competition on the merits is now back in all discussions (and, for some, central to determine whether or not a given practice amounts to an abuse). Against this background, the paper seeks to answer two interrelated questions. What is competition on the merits? Does Article 102 TFEU apply to normal conduct or is an abuse an inherently ‘abnormal’ or ‘wrongful’ act?

It makes sense to start with the second. An overview of the case law suggests that normal conduct can be subject to Article 102 TFEU. ‘Normal’, in this context, means that the strategy is potentially pro-competitive (that is, firms can have recourse to it for non-exclusionary reasons) and that can be implemented by both dominant and non-dominant firms (that is, it is not the exclusive province of the former).

Exclusive dealing, tying and rebates (not to mention a refusal to deal with a third party) are all normal in this sense. However, we know well that they may amount to an abuse of a dominant position where certain conditions are met.

How about competition on the merits? The paper explains that this notion has become an irritant in the case law, in the sense that it is a source of confusion and frictions.

Tensions can be explained in part by the fact that the notion of competition on the merits was introduced at a time when the prevailing ideas about abusive conduct were very different from today’s.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was assumed that abusive practices could be identified ex ante and in the abstract. The underlying premise was that it was possible to draw a clear dividing line between unlawful conduct and legitimate expressions of competition on the merits.

The case law that followed (as well as the evolution of legal and economic thinking) moved away from these ideas. Whether or not most practices amount to an abuse is a context-specific exercise, not an abstract one detached from ‘all the circumstances’ surrounding their implementation.

If most practices are neither inherently good nor bad and the application of Article 102 TFEU is very much context-dependent, what is the contemporary role of competition on the merits?

My argument is that the notion of competition on the merits has role to play in the contemporary case law if it is interpreted in light of the ‘as efficient competitor’ principle (which has been a consistent feature in the judgments delivered over the past decade, including in yesterday’s ruling in Superleague).

Against this background, the argument provides a positive and a negative definition of the notion.

From a positive perspective, a dominant firm can be said to compete on the merits where it gets ahead in the marketplace with, inter alia, better, cheaper and/or more innovative goods or services.

The corollary to this positive definition is that, where the exclusion of a rival is attributable to the fact that the latter is less attractive along one or more parameters of competition, the practice is not abusive. Any exclusion would be the manifestation of competition on the merits.

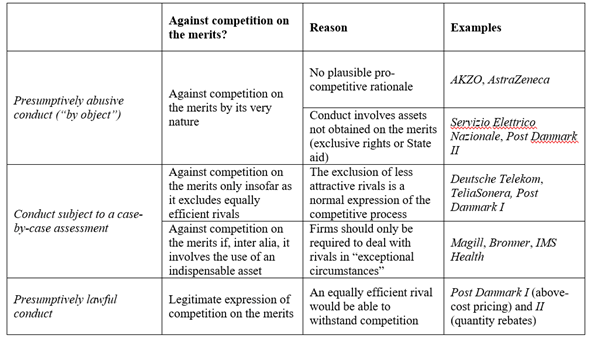

From a negative perspective, a dominant firm does not compete on the merits in three instances.

First, where the practice has an anticompetitive object (that is, it makes no economic sense other than as a means to restrict competition). Pricing below average variable costs is the classic example in this regard.

Second, where the strategy involves the use of assets not developed on the merits (that is, assets that have been developed with State support, either in the form of State aid or the award of exclusive rights). In this instance, which was at stake in Post Danmark II, the ‘as efficient competitor’ principle would not be the benchmark against which the lawfulness of the practice is assessed.

Third, where the practice, while potentially pro-competitive, causes the exclusion of equally efficient rivals. In the latter, instance, the question of whether the behaviour is an expression of competition on the merits and that of whether it is exclusionary collapse into one and the same issue.

Based on the above, one can classify the case law in the manner you see on the Table below:

I would very much welcome your comments on the paper. As usual, I have nothing to disclose.