LSE Short Course on State Aid and Subsidy Regulation (Feb 2026 edition)

The new edition of the LSE Short Course on State Aid and Subsidies Regulation will be organised, again, in February of this year. I really look forward to it, as it comes at a time when major developments are reshaping the discipline in fundamental ways (so fundamental, in fact, that they inspired me to write a whole book on them).

The Short Course will cover all these developments, including the changes brought about by the Clean Industrial Deal framework, the emerging administrative practice under the EU Foreign Subsidies Regulation and the growing case law interpreting the UK Subsidy Control Act 2022.

It always seemed to me that State aid and subsidies are learnt ‘along the way’ by many lawyers. The point of this Short Course is precisely to provide what many might miss: the necessary basics and conceptual framework to navigate the discipline and remain on top of contemporary trends.

As usual, the Short Course will take place online and it is designed with full-time professionals in mind. Attendance will be capped at around 25 participants to maximise interaction (always one of the big pluses of this format: every edition is shaped by the discussions that take place).

The sessions will be on four consecutive Thursdays: 6th, 13th, 20th and 27th February (at the usual time: 2pm to 6pm London time).

An LSE Certificate will of course be available upon completion, along with CPD points for practitioners.

If you have any questions about the organisational aspects of the two courses, do not hesitate to contact my wonderful colleague Mandy Tinnams: A.Tinnams@lse.ac.uk.

The next frontier: can an exploitative (i.e. non-exclusionary) refusal to deal be abusive?

In competition law terms, last year was marked by Android Auto. Following the judgment, the applicability of the Magill and Bronner doctrines depends on two questions: (i) whether the dominant firm has developed the assets ‘solely for the needs of its own business‘ and (ii) whether a duty to deal would ‘fundamentally alter the economic model‘ on which the development of the assets relied.

The refusal to deal doctrines are only relevant where these two cumulative conditions are met. Where either of these conditions fails, the potentially abusive nature of the refusal will be evaluated in light of the standard effects analysis that applies as a default under Article 102 TFEU.

A central question that was never tackled by the Court in Android Auto is whether Enel and Google are competitors in the relevant adjacent market (and, similarly, whether Enel’s app and Google Maps were rival products).

The whole analysis is carried out on the assumption that Enel and Google are indeed competitors in the said adjacent market, even if the latter is merely hypothetical or has shifting boundaries.

There were good reasons for the Court to make this assumption. After all, the Magill and Bronner doctrines only provide support for intervention where the dominant firm and the one requesting access are actual or potential competitors.

As the law stands, there is no basis in the case law to support the idea that Article 102 TFEU can be relied upon to compel a dominant firm to deal with a non-competitor – what I call an exploitative refusal to deal.

It would therefore be necessary to develop an ad hoc doctrine extending the range of instances where an undertaking can be order to share an asset with a firm with which it has chosen not to deal. In the alternative, the Court could choose to expand the reach of Android Auto.

In a sense, Android Auto lends itself quite naturally to an extension along these lines. The fundamental idea behind the judgment, after all, is that a dominant firm having developed a (partially) open platform must accept that firms operating in and around the platform become involved in its design.

In such circumstances, the only twist that would be needed relates to the assessment of anticompetitive effects. Instead of exclusionary, such effects would be exploitative.

One could argue, for instance, that, by failing to feature a particular application (or category thereof), end-consumers would be deprived of more attractive functionalities without an objective justification.

Where the dominant firm is already giving access to another provider in the relevant category, one could argue, in addition, that refusing to deal with another provider amounts to exploitative discrimination within the meaning of Article 102(c) TFEU.

Such an expansion would not be wholly uncontroversial. A potential argument against it is that it would probably amount to compelling a firm to deal in virtually every scenario (so long as there are no technical reasons justifying the refusal, that is). In the same vein, the exploitation route would allow claimants and authorities to circumvent the need to establish the exclusionary effects of the refusal.

It is difficult to say whether the scope of Article 102 TFEU will expand in this direction. What one can certainly say is that it would not be surprising if the expansion occurred. The legal shift would bear all the hallmarks of the new EU competition law, and in particular the trend towards regulatory-like intervention and the blurring of lines between exploitation and exclusion.

Looking back and looking forward (plus a resolution): a year in research and writing

As the year comes to a close, I thought I would share some of the research that got published this year. It was an unusual exercise, as every one of the pieces reminded me of what is yet to come — and which I hope I will be sharing in the coming months. The exercise also delivered a resolution: increase the output on the blog (easily achievable given this year’s meagre production).

This year saw the publication of two articles (frustratingly, other pieces got stuck in the peer review process much longer than anticipated):

- Remedies in EU Antitrust Law (see here). published in Open Access in the Journal of Competition Law and Economics.

- Judicial review in EU merger control: towards deference on issues of law? (see here), publised, also in Open Access, in European Law Open.

In addition, I am delighted to announce that ‘How Android Auto Reshapes the Law of Refusal to Deal (and What it Means in Practice)‘ (see here), which received the AdC Competition Policy Award, has been accepted for publication and is forthcoming in World Competition.

I am also delighted that two book chapters were published this year:

- State aid control beyond the EU: legal convergence and unilateral expansion (see here), jointly authored with Damien Neven, was published in the long-awaited second edition of the treatise and brainchild of Philipp Werner and Vincent Verouden, EU State Aid Control: Law and Economics.

- Hoffmann-La Roche and the Notion of Abuse, published in Paul Craig and Robert Schütze (eds), published in Landmark Cases in EU Law, Volume 2. This piece was an interesting exercise in legal history, which got me looking back at the early days of competition law enforcement in Europe. The volume as a whole is really interesting. I will be sharing it on ssrn as soon as the embargo is lifted.

As mentioned the other days, morever, Luca Prete and Leila Rezki have put together a Liber Amicorum in Honour of Nils Wahl, to which I proudly contributed and which is available here.

Here’s wishing you a wonderful 2026!

NEW PAPER: The Categorisation of Practices in EU Competition Law

I have just uploaded on ssrn (see here) a paper entitled ‘The Categorisation of Practices in EU Competition Law‘. It will be coming out in the forthcoming Liber Amicorum in Honour of Nils Wahl, jointly edited by Luca Prete and Leila Rezki.

As I explain, the definition of legal categories is one of the core functions that the EU courts are asked perform in the area of competition law (and, dare I add, in EU law at large). Wouter Wils explained a while ago that ‘all human thinking‘ involves the use of categories. It is therefore an illusion to think that the law can be administered without resorting to them. What matters, Wouter rightly added, is not whether categories exist, but whether those used are sound.

The paper explains the fundamental role of categories in a field, like EU competition law, that revolves around open-textured concepts such as ‘restriction of competition’ or ‘abuse’. It also discusses, second, the main approaches that might be followed to the characterisation of conduct. Finally, it provides an overview of the techniques that the Court of Justice has followed over the years to define and refine categories.

It would be great to get your thoughts on the piece. And keep an eye on the launch of the book!

Thoughts on Case C‑2/24 P, Teva: pay-for-delay is the saga that keeps on giving

The meaning and scope of Article 101(1) TFEU is much clearer than it was just a decade ago (see here for a discussion). This relieving reality is in no small part a consequence of the steady stream of cases dealing with pay-for-delay practices in the pharma sector.

Rulings addressing pay-for-delay issues (and variations thereof) have provided the core test to establish whether a practice amounts to a restriction by object (since Generics, the issue is whether the only plausible explanation for it is the restriction of competition) and emphasise that, as far as Article 101 TFEU is concerned, anticompetitive effects will be assessed against the relevant counterfactual (a point on which I elaborated here).

More generally, the pay-for-delay saga illustrates that context is everything: as recently explained by Advocate General Emiliou in Tondela (here), a restriction of competition can never be established in the abstract. Whether it is a by object or by effect infringement, it is necessary to consider the circumstances surrounding the agreement.

One could have thought that these cases could not provide more clarity on the analytical framework to assess restrictions of competition. The Court judgment in Teva, however, has showed that the saga still has much potential to shed light on Article 101(1) TFEU.

Assessing the object of a practice in its context is not the same as evaluating its effects

The ruling in Teva is particularly helpful in that it engages with a line of reasoning that has become commonplace in recent years. According to some commentators, the contextual assessment of restrictions by object is problematic insofar as it blurs the line between object and effect.

I have never been persuaded by that criticism, which does not reflect the reality of the case law. Assessing the object (the rationale, that is) of a practice in the relevant economic and legal context is fundamentally different from establishing its actual or potential effects in the market (or markets) in which it is implemented.

It is certainly true that, once the anticompetitive object of an agreement is established, it is not necessary to ascertain its effects (something that the Court briefly reminds in Teva, paras 121-124, when dealing with the second plea raised by the appellants). It does not follow from this fact, however, that a contextual analysis is not required.

More generally, nowhere is it written that proving the object of an agreement should ignore the surrounding circumstances, or that it should be easy or straightforward to do so. The idea that the ‘object’ category is something of a ‘shortcut’ is foreign to EU law. It is borrowed from US antitrust law, which is fundamentally different from its European counterparts in more ways than one.

The appellants in Teva sought to advance a variation on this argument. They claimed, more precisely, that the General Court had conflated object and effect by, inter alia, introducing a counterfactual assessment, thereby making it impossible for the parties to the agreement to discharge their burden of proof.

The Court summarily dismissed these claims. When ascertaining the rationale, or object, of an agreement, it makes sense to consider the set of incentives it creates (paras 77 and 78). I would say more: how a practice influences the incentives of the parties will often provide a vital clue about what it seeks, objectively speaking, to achieve. That assessment does not entail an evaluation of the effects of the agreement in any way, contrary to what the parties claimed.

In the same vein, the Court concludes, the General Court did not require the parties to show what would have happened in the absent of the agreement. The relevant question remained that of whether the contentious transactions could be plausibly explained other than as a means to restrict competition (para 100). To the extent that it did, the General Court’s assessment remained firmly within the boundaries defined by Generics.

The unit of analysis is the clause, but context matters

The preceding case law had been clear in stating that the relevant unit of analysis is the clause, not the agreement as a whole (and this includes the crucial issue of severability). Examples abound. Arguably the canonical one is Pronuptia, where the Court distinguishes between the clauses that are ancillary to the operation of the franchise and those that are not (which, moreover, were found to restrict competition by their very nature).

The Court’s long-standing position is the only reasonable one. It would be too easy for the parties to avoid a finding of a ‘by object’ infringement if they were allowed to invoke the non-restrictive nature of the agreement taken as a whole. In effect, it would empty the ‘object’ category of its substance. For instance, a standard-setting agreement could be used as a vehicle to conceal a cartel agreement.

What Servier pointed out, and the Court mentions again in Teva (para 68) is that the analysis of the clauses cannot be undertaken in isolation. It may be the case that the clauses, taken together, are different aspects of a common strategy. If that is true, it is only reasonable that they are analysed together. By the same token, it is futile for the parties to try and argue that a given clause, examined in isolation, is not restrictive by its very nature. Such an interpretation would, again, entail a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the analysis under Article 101(1) TFEU.

At the end of the day, the Court’s clarification in Servier and Teva is another way of saying that context is everything at the ‘by object’ stage. The contextual analysis must by definition commence by looking at the agreement of which the clauses are a part. It is the first starting point, before shifting to factors such as the nature of the products or the dynamics of competition within the sector. The first step of the contextual assessment is likely to provide valuable hints about their nature.

Consider the example of price-fixing. There is a difference between a ‘naked’ price-fixing clause and one that is inserted in an agreement that pursues a non-restrictive aim. For instance, the Commission has long held (and rightly so, since the Court itself held just as much in Gottrup-Klim) that price-fixing clauses in the context of a joint purchasing agreement are not necessarily restrictive by object (see here). It has recently provided a good example that applies to SEP licensing.

Google AdTech: towards an ad hoc procedure for the design and implementation of remedies

The Commission Decision in Google Ad Tech exemplifies, better than any other, the shift in the centre of gravity of competition law enforcement towards remedies (see here for a more extensive discussion of this point). It also shows that remedy design is probably the single most important aspect to address in the ongoing reform of Regulation 1/2003.

In the current economic and technological landscape, a finding of infringement no longer marks the end of a case. This milestone is, as they say, just the end of the beginning. The effectiveness of enforcement, in digital and others markets, depends less on establishing an abuse of dominance than it does on ensuring that the infringement is brought to an end by means of a workable and well-crafted remedy.

Towards a structured framework for the design and implementation of remedies

The approach that the Commission is following in Google AdTech is a (welcome) innovation against this background. It has implemented what is, in effect, an ad hoc procedure to define the obligations with which the firm must comply. As this post is being finished, the Commission and Google are in the midst of conversations in the context of this informal procedure (see here for a recent update on the matter).

The aftermath of the decision suggests that the Commission acknowledges that merely ordering a firm to bring the infringement to an effective end no longer does the trick, and neither does a ‘principles-based’ approach that requires an undertaking to abide by an open-textured standard (such as non-discrimination). As I have written elsewhere, the complexity of remedies cannot be wished away by authorities.

Even if only de facto for the time being, Google AdTech suggests that the design and implementation of the remedy will, from now on, follow a structured framework that is independent from the finding of infringement.

Pursuant to the Automec doctrine, this ad hoc procedure gives the firm the chance to come up with a proposal to bring the infringement to an effective end. On the other hand, it allows the Commission to evaluate whether the undertaking’s proposal indeed addresses the concerns identified in the decision.

Where necessary (and this is the crucial third step), the Commission will specify the obligations with which the firm must comply (just like it does in the context of a commitments procedure). On this point, it has clearly signalled that it may adopt structural measures breaking up Google’s adtech business.

What matters, irrespective of the nature of the remedy, is that the duties imposed upon the firm are spelled out clearly and in sufficient detail to ensure immediate and full compliance.

The need for a structured framework: the experience of Google Shopping

The experience of the past few years shows that a framework for the specification of remedies is indispensable for the effective operation of the competition law regime. Delegating the design and/or implementation of remedies to firms is in nobody’s interest, neither that of the competition authority, nor the addressees of the decision nor of third parties potentially benefitting from intervention.

More importantly, it is now difficult to dispute that the ‘principles-based’ approach to remedial action has failed. The uncertainty to which it gives rise has major practical consequences, which were dramatically exposed last week (see here).

Google Shopping is a case where controversy around compliance with the remedy never really went away. Whether or not the measures implemented by the firm back in 2017 brought the infringement effectively to an end has always been (and remains) contentious.

It is against this background of perpetual limbo that a German court awarded damages to two of Google’s rivals on the market for price comparison last week. Crucially, the damages award extends to the period following the adoption of the Commission decision, and is therefore based on the assumption that the firm never actually complied with the principles-based remedy imposed.

Even though the Commission never opened non-compliance proceedings against Google, the absence of a decision formally and positively declaring that the infringement had been brought to an effective end paved the way for the award of damages beyond 2017.

This judgment suggests that any remedy implemented following a ‘principles-based’ approach is potentially vulnerable to challenge and, as such, a source of legal and non-legal uncertainty.

Moving forward: codifying the framework

The Commission’s introduction of an ad hoc remedial framework in Google AdTech is therefore the right way forward. Acknowledging the realities and demands of contemporary industries is not just wise but indispensable. It would be desirable if the ad hoc remedies procedure were improved along three dimensions.

First, transparency. The exchanges between the firms and the authority should benefit from similar levels of openness as those observed in the context of commitment procedures. What the firm proposes as per Automec and the authority’s assessment of the proposal should not happen behind closed doors.

Second, third-party involvement. One of the advantages of the commitments procedure within the meaning of Article 9 of Regulation 1/2003 is that obligations are ‘market-tested‘ with stakeholders. A structured procedure would give these stakeholders a meaningful chance to provide input about the proposals and to express their concerns, if any.

Third, codification. Ideally, this procedure would be enshrined in a reformed Regulation 1/2003. As a second best, it could at least be codified at the internal level (the 2019 version of the Manual of Procedure was, say, succinct about the issue or remedies and would definitely benefit from a revamp and further detail).

EDITORIAL: Law and technocracy to protect democracy

An editorial of mine has recently come out with the Journal of European Competition Law & Practice (JECLAP). It is available here. The point it makes is simple: the first instinct of illiberal regimes is arguably to disregard the law and ignore expertise (whether it relates to climate change, vaccine safety or any other issue).

I argue, against this background, that, if competition law is to play a role in the protection of democracy and its institutions, it must resist the temptation to abandon law and expertise in the name of expediency or effectiveness. Such a move is not only likely to weaken policy-making and affect its quality, but would inevitably backfire over the long run.

I look forward to your thoughts on it. I explored the same ideas in the keynote lecture delivered in honour of Heike Schweitzer a few months ago (see here).

NEW PAPER: How Android Auto reshapes the law of refusal to deal (and what it means in practice)

I have uploaded on ssrn a new paper (see here) a paper that discusses the judgment of the Court of Justice in Android Auto as well as its substantive and institutional implications. I am pleased that the paper received yesterday the AdC Competition Policy Award, organised every year by the Portuguese Competition Authority.

The way in which Android Auto has changed the law of refusal to deal, it seems to me, may not have been fully appreciated. To make this point, it is sufficient to apply the Court’s reasoning in Android Auto to the facts at stake in Bronner. The latter would have been decided differently; evidence of indispensability would not have been required to establish an abuse.

As I explain in the paper, this difference is a function of the way in which Android Auto (re)interprets the indispensability condition. In Bronner and Magill, whether or not the dominant firm had kept the assets ‘for the needs of its own business‘ was assessed by reference to the relevant market concerned by the refusal. It was therefore irrelevant that the TV channels in Magill were licensing their copyright to newspapers (but not weekly magazines) or that Mediaprint was printing and distributing another publication in Bronner at the time of the facts.

The analytical approach followed in Android Auto construes the indispensability condition differently. According to the new doctrine, where the dominant firm is dealing with a third party in market A, it can no longer invoke indispensability in relation to a refusal concerning market B. For the same reason, the judgment has significantly reduced the scope of the refusal to deal case law.

This transformation has obvious implications for digital markets. Dominant players in these markets often run systems that are partially open and partially closed. This said, the criteria followed by the Court suggest that the ruling is likely to have an impact in other industries and markets.

In any event, the implications of the judgment go beyond the shrinking of the refusal to deal doctrines. Android Auto allows for intervention that is not confined to a mere duty to deal. A dominant firm may indeed be required not just to share an input or infrastructure with third parties, but to redesign its assets by taking into account the demands of the said third parties. In this sense, the operation of the infrastructure becomes a cooperative venture.

I look forward to your comments on the paper. And thanks again to the AdC!

JOB OPENING: want to join LSE Law School as an Assistant Professor of Competition Law?

LSE Law School is looking for an Assistant Professor of Competition Law, to join the Faculty in September 2026. All information in terms of requirements, conditions and on how to apply can be found here: https://www.jobs.ac.uk/job/DOZ822/assistant-professor-in-law-competition-law.

Needless to say, the competition law team could not be more excited about the prospect of enhancing our teaching and research capabilities in the field.

I can tell from experience that LSE Law School is a non-hierarchical environment that allows you to flourish and find your voice as a scholar. Teaching and administrative duties are light in the first few years (up until promotion to an Associate Professorship). In addition, you will benefit from an annual (and generous) research allowance.

You may be asked to contribute to teaching in foundational subjects, but our competition law curriculum is large and varied. In addition to a dedicated undergraduate module, the LSE Law School now offers an LLM programme with an ample array of competition law options, ranging from State aid and subsidies to the regulation of competition in digital markets.

If you are interested in applying and would like to have an informal chat about the post, do not hesitate to get in touch with me.

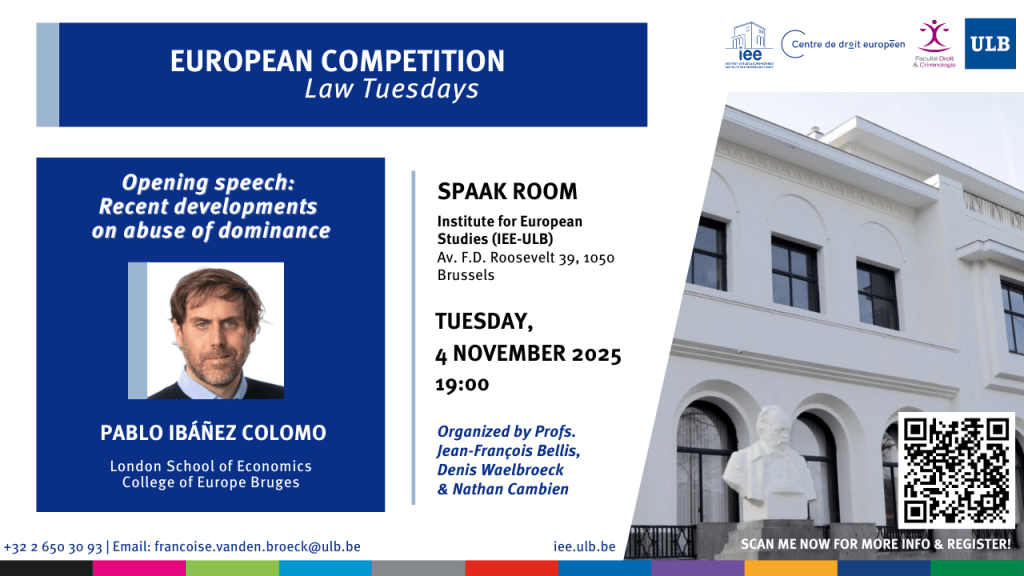

SAVE THE DATE: Recent developments on abuse of dominance (Brussels, 4th November at IEE-ULB)

With every new academic year comes a new edition of the mardis du droit de la concurrence, This series has been around pretty muchsince the dawn of European competition law. It continues to be a unique venue to get a sense of the evolution and direction of travel of our field, more recently under the expert leadership of Denis Waelbroeck and Jean-François Bellis (now joined by the great Nathan Cambien).

The programme for the new academic year is now out (see here). It includes talks that have become classic fixtures, such as Fernando Castillo de la Torre‘s overview of the case law in the area of cartels and provides a complete tour d’horizon of all areas of enforcement, featuring both Commission officials and private practitioners.

Advocate General Laila Medina will be closing this year’s series with a *lundi du droit* (11th May 2026) with a speech on ‘EU competition law and the Court of Justice‘.

I am honoured (and grateful) to have been invited to open this year’s series on Tuesday 4th November (7pm Brussels time) with a discussion on the recent developments on abuse of dominance. More info on can be found on the flyer above. I really look forward to seeing many of you there!