Mondelez: abuses by object, consistency and the administrability of Article 102 TFEU

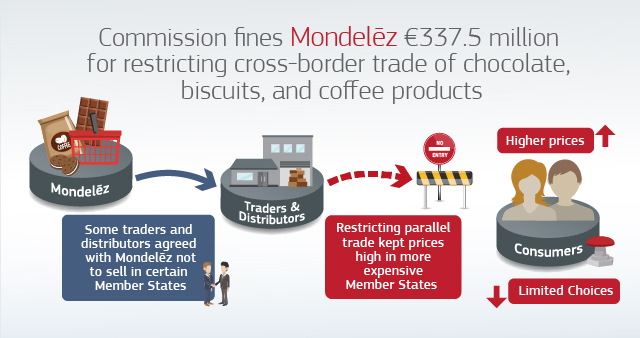

Last week, the Commission announced that it has fined Mondelez for engaging in a series of practices aimed at restricting intra-EU trade. There is nothing new or special about Mondelez’s conduct.

The decision comprises bread-and-butter cross-border limitations (which have always been sanctioned as restrictive by their very nature under Article 101 TFEU) and unilateral conduct with the very same object. The latter included the refusal to sale a product to a broker and the decision to cease supplies. Both have been found to amount to an abuse of a dominant position.

The above does not mean that the decision is uninteresting. It is, but for a different reason. We have seen much talk, in the context of the ongoing review of Article 102 TFEU enforcement, about ‘by object’ abuses and, more generally, about whether it is necessary to show anticompetitive effects in relation to every potentially abusive practice.

The Mondelez case provides, against this background, two examples of practices that are deemed abusive without the need to establish their restrictive impact in the relevant economic and legal context. As is clear from the press release, this is so because their very object is to restrict intra-EU trade (and as such inherently anticompetitive in the EU legal order).

As explained earlier this year, the Court of Justice demands that Articles 101 and 102 TFEU be interpreted consistently. If restrictions to intra-EU trade are, in principle, restrictive by object under the former, it is only logical that they are treated in the same way under Article 102 TFEU. I, for one, look forward to reading the decision and finding out how the Commission goes about the question.

Mondelez is interesting for another reason. It reveals that the Intel doctrine (whereby dominant the firms have the chance to show that a practice is incapable of restricting competition) will sometimes prove plain ineffective from the perspective of a dominant firm. By the same token, there will be instances where any claims about the lack of effects can be summarily dismissed by an authority.

It would be wrong to assume, in other words, that Intel requires an authority to engage in analysis of effects in every instance. For the same reason, it would be wrong to present the doctrine as an obstacle to the administrability of Article 102 TFEU. The more egregious the infringement, the more limited the relevance of Intel and the less likely the need to engage in an analysis of effects.

Conduct aimed at limiting intra-EU trade (the quintessential example of egregious conduct, alongside cartels) is only incapable of restricting competition in very limited instances, namely (i) where the absence of cross-border trade is attributable to the regulatory context, not to the practice; and (ii) where allowing such trade would empty an intellectual property right of its substance (as in Erauw-Jacquery).

The extent to which arguments of this kind have limited traction when intra-EU trade is at stake became apparent in the Valve case, discussed here. That case related to the application of Article 101 TFEU, but the insights would be relevant, almost word for word, in the context of Article 102 TFEU.

As I say, one decision to look forward to reading.

Leave a comment