Archive for November 28th, 2024

On the Article 102 TFEU Guidelines (III): what is an anticompetitive effect?

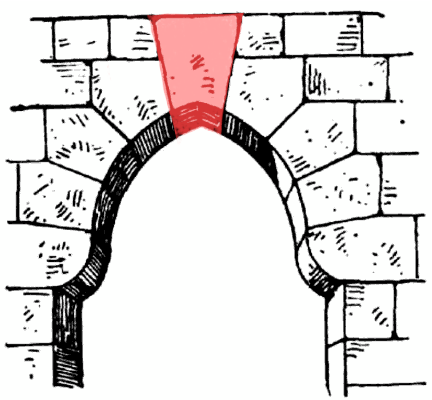

This week’s post focuses on what is probably the single most complex point of law considered in the Draft Guidelines on exclusionary abuses. It is also the keystone of the whole venture, in the sense that it could mark its fate.

The case law of the past decade has very much emphasised the need to engage in a meaningful assessment of the effects of certain practices. It is now undeniable that some conduct is only caught by Article 102 TFEU where it can be shown to have an actual or potential impact on competition.

This so-called ‘effects-based approach’, now enshrined in the case law, is not a capricious hurdle aimed at making enforcement more difficult or less effective. It is rather the acknowledgement that many, if not most, practices do not necessarily pursue an exclusionary aim and, similarly, do not invariably deteriorate the competitive process (even when implemented by a dominant firm).

The (daunting) challenge, against this background, is to get the definition of anticompetitive effects right. Getting the definition right, in this context, means, first, providing the basis for a meaningful assessment (that is, one that is not merely a formality); and, second, making it possible to discern what an effect is and what it is not.

What an effect is not: lessons from the case law

Part of the difficulty that comes with fleshing out the concept is that the case law is far more illuminating about what an anticompetitive effect is not (as opposed to what it is). The issue, as the law stands, is best approached in a negative manner.

It is clear from the case law, to begin with, that an anticompetitive effect is not synonymous with harm to consumer welfare. Therefore, the former can be established without showing the latter (and, more importantly, without the latter necessarily occurring, whether actually or potentially).

Second, a mere competitive disadvantage and/or a limitation of a firm’s freedom of action do not amount, in and of themselves, to an anticompetitive effect within the meaning of Article 102 TFEU.

The latter point has long been clear. If anything, it has become even more difficult to dispute following Servizio Elettrico Nazionale and the appeal judgment in Google Shopping. As reminded in para 186 of the latter, the fact that a vertically-integrated dominant firm discriminates against its non-integrated rivals (which necessarily places them at a disadvantage) is not abusive in and of itself.

Similarly, the fact that a practice (say, a system of standardised rebates) limits the freedom of action of a dominant undertaking cannot, in and of itself, substantiate a finding of anticompetitive effects. The clarification of this point is arguably the most valuable contribution made by Post Danmark II to the body of case law.

The challenge, in theory and in practice, is to identify the point at which a competitive disadvantage and/or limitation of a firm’s freedom of action are significant enough to amount to anticompetitive effects.

Third, the fact that the rivals of a dominant undertaking lose customers as a result of the behaviour of the dominant firms does not necessarily mean that the said behaviour has actual or potential anticompetitive effects.

According to the case law, there will be no anticompetitive effects, whether actual or potential, for as long as rivals remain willing and able to compete. Post Danmark I provide an ideal case study (if only because the Court unambiguously signalled the absence of effects in light of the facts of the case and the evolution of the relevant market).

The definition of anticompetitive effects in the Guidelines (and its practical consequences)

Capturing the essence of the case law is not an easy task. Crafting a definition that is operational (in the sense that its meaning can be grasped by national courts and authorities) is even more difficult.

The Commission could not avoid, alas, trying its hand at the challenge. In para 6 of the Draft Guidelines, it proposes to define the notion of anticompetitive effects as referring to:

‘any hindrance to actual or potential competitors’ ability or incentive to exercise a competitive constraint on the dominant undertaking, such as the full-fledged exclusion or marginalisation of competitors, an increase in barriers to entry or expansion, the hampering or elimination of effective access to markets or to parts thereof or the imposition of constraints on the potential growth of competitors‘.

The fundamental point to make in relation to this definition is that it does not fully shed light on what an effect is (and, indeed, what an effect is not).

More precisely, the definition enshrined in the Draft Guidelines could be reasonably interpreted as suggesting that virtually any competitive disadvantage amounts to an anticompetitive effect. According to the current drafting, any ‘hindrance’ to the exercise of a competitive constraint would be sufficient, in and of itself, to establish an abuse.

Such an approach may not be obvious to square with the case law described above. As rulings like Servizio Elettrico Nazionale and Google Shopping show, ‘hindering‘ rivals’ ability to exercise competitive pressure does not necessarily lead to actual or potential anticompetitive effects.

The practical consequences of such an expansive understanding of the notion of anticompetitive effects are arguably more significant than the tension with some aspects of the case law.

Accepting that any ‘hindrance‘ can amount to an anticompetitive effect means accepting that pretty much any strategy implemented by a dominant firm amounts to an abuse of a dominant position. With such a broad definition, one could always make a plausible case that the requisite threshold is met.

The assessment of effects, in other words, would become a formality (actual or potential effects would always be shown to exist), rather than a meaningful one.

One can expect, in the same vein, actors in the system to exploit the expansive understanding of the notion of abuse before national courts (which, unlike competition authorities, lack the ability to prioritise cases).

If enforcement moves down this road, it may take a while before the Court of Justice is given the chance to refine the definition of effects and correct deviations from the case law. In the meantime, the legal community will have to learn to live with a significant degree of legal uncertainty around the meaning and scope of Article 102 TFEU.

A proposed definition of anticompetitive effects

One can think of a definition of anticompetitive effects that more faithfully reflects the essence of the case law and ensures, in the same vein, that the assessment remains meaningful. The notion can be construed, for instance, as follows:

‘Anticompetitive effects exist where the practice reduces rivals’ ability or incentive to compete to such an extent that the competitive pressure to which the dominant firm is subject is reduced as a result’.

Next week, I will address the ways in which this definition can be made operational (and administrable) so that it can be applied in concrete cases. In the meantime, I would very much welcome your thoughts.