Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

New Paper | Anticompetitive Effects in EU Competition Law

I have uploaded a new paper on ssrn (see here) on Anticompetitive Effects in EU Competition Law.

What was the impetus behind the paper? The ‘effects-based approach’ have long been part of discussions, yet there are only a handful of judgments addressing the analysis of effects in a meaningful way.

There is still some uncertainty about what anticompetitive effects are and how they are measured in concrete cases. On the other hand, the Court has already clarified the key issues. Against this background, I felt I could contribute to the debate by bringing together the various strands of the case law and present them in a single framework.

The paper tries to organise what we know about effects around the main variables that shape its meaning and scope, and in particular:

- The time dimension: actual and potential effects (and retrospective and prospective analysis).

- The dimensions of competition (inter-brand and intra-brand) and the counterfactual (ex ante and ex post).

- The meaning of effects: effects can mean many things, from a competitive disadvantage, to harm to the market structure to harm to consumers. The analysis is particularly sensitive to the way this variable is defined.

- The threshold of effects: again, the analysis would vary substantially depending on whether it is enough to show that effects are plausible or whether instead it is necessary to establish that effects are likely to happen.

It would not be obvious to summarise the paper in a single post (I will probably add some dedicated entries). It may make sense to mention, however, that the notion seems to have acquired a clear meaning over the years.

In particular, it seems like effects are more than a competitive disadvantage and/or a limitation of a firm’s freedom of action (think of Deutsche Telekom, Post Danmark I, MEO, Maxima Latvija, Generics and, in the context of merger control, Tetra Laval and GE/Honeywell).

We know from experience that having an edge over rivals is not necessarily fatal for competition; it may even spur rivalry (think of Post Danmark I, where rivals were able to withstand a below-cost price campaign). A limitation of a firm’s freedom of action is not enough either (think of Generics, where the Court held that the effects should be more than the impact of each individual agreement).

What matters, the case law suggests, is whether firms’ ability and/or incentive to compete is affected by a practice or transaction, and this to such an extent that competitive pressure is reduced. Thus, no effects would exist where firms on the market are still willing and able to compete.

The threshold of effects is another contentious issue. We all know that effects can be actual or potential. The real question, when the analysis of potential effects is at stake, is whether it is sufficient to show that harm is plausible or it is ‘more likely than not’ (to use AG Kokott’s expression in Post Danmark II).

If we pay attention to what the Court does, it appears that, regarding ‘by effect’ conduct under both Articles 101 and 102 TFEU (as well as mergers), the negative impact of a practice should be probable (‘more likely than not’) and not simply plausible. Just think of how the analysis was actually conducted in, inter alia, Delimitis, TeliaSonera, Post Danmark II, Kali & Salz and Microsoft/Skype.

As far as ‘by object’ conduct is concerned, it is sufficient to show that harm to competition is ‘plausible’ (the threshold, in other words, is much lower). Bananas or Toshiba are clear examples in this regard, and reveal how much the analysis differs between the ‘by object’ and ‘by effect’ stages.

As I say, I will probably follow up with more posts on the paper. In the meantime, I very much look forward to your comments.

The ‘robust and reliable experience’ requirement in Budapest Bank: why it is a consequence of the case law (and why it is not relevant in pay-for-delay cases)

The ‘robust and reliable experience’ requirement: a natural consequence of the case law

An interesting aspect of Budapest Bank is the reference to ‘robust and reliable experience’. According to the Court, it is not appropriate to categorise conduct as a ‘by object’ infringement absent sufficient accumulated knowledge about the nature, purpose and potential (pro- and anticompetitive) effects of a practice (para 76).

This requirement cannot come as a surprise. Cartes Bancaires and Generics already made a reference to experience. If one considers the logic of the case law as a whole, moreover, it looks like this requirement was already implicit in the Court’s approach.

One can think of at least two reasons in this regard, one relating to the allocation of the burden of proof in the system and the other one to the value placed to expert knowledge by the EU courts.

Experience, ‘reasonable doubts’ and the allocation of the burden of proof

The Court held in Generics that the categorisation of a practice as a ‘by object’ infringement would not be appropriate where ‘reasonable doubts’ remain about whether the agreement is capable of generating pro-competitive effects. In such circumstances, it would not be possible to rule out that the agreement would improve the conditions of competition that would have existed in its absence.

Where there is insufficient experience about the rationale behind a practice in a particular economic and legal context (given, for instance, the features of the relevant market, as in cases like Budapest Bank or Cartes Bancaires), it would not be possible for an authority or claimant to dissipate any such ‘reasonable doubts’. For the same reason, they would not be able to discharge their legal burden of proof.

On experience and expertise as a constraint on administrative action

There is another reason why the ‘experience test’ was an implicit element of the case law. The EU courts have always seen expertise and expert knowledge as a safeguard against arbitrary decision-making. Cases like Airtours, Tetra Laval and, indeed, Cartes Bancaires, show that the Commission (or any other administrative authority subject to EU law) cannot ignore the body of knowledge accumulated over the years.

Against this background, it is only logical that the Court requires that the categorisation of a practice as a ‘by object’ infringement is grounded on consensus positions refined over time. By the same token, absent sufficient evidence about the rationale behind a practice, authorities should refrain from coming to conclusions that cannot be adequately substantiated by expert knowledge.

The issue can be aptly illustrated by reference to a concrete example: if, at the time of the adoption of a decision the pro-competitive effects resulting from a practice are not yet well understood, an authority would not be in a position to conclude that the practice in question has, as its object, the restriction of competition (in such circumstances, ‘reasonable doubts’ in this sense would not be dissipated).

The ‘robust and reliable experience’ requirement and pay-for-delay cases

It is natural to ask oneself whether the ‘robust and reliable experience’ test has a role to play in pay-for-delay cases. After all, it is not unreasonable to argue that these cases are new and that there may not be sufficient accumulated knowledge to conclude that they are restrictive of competition by object.

Contrary to this view, I fail to see how the ‘robust and reliable experience’ test could be of assistance to defendants in pay-for-delay settings. The test laid down in Generics seeks to ascertain, in essence, whether the settlement conceals a cartel-like market-sharing or market-exclusion arrangement (paras 76-77).

One cannot seriously dispute that there is an abundance of experience about the nature, purpose and net anticompetitive effects of cartels (since they have no plausible purpose other than the restriction of competition, they can only do harm). There is probably more experience about these agreements than about any other. This point is central to Cartes Bancaires (para 51) and Budapest Bank (para 36).

It has long been known, in addition, that cartel arrangements can be concealed as a pro-competitive venture. There is so much experience on this question that the Guidelines on horizontal co-operation agreements repeatedly allude to this point. For instance, a standard-setting arrangement can hide a cartel, as in the venerable ANSEAU-NAVEWA case.

Can an intellectual property settlement conceal a cartel arrangement? Do we have experience in this sense? It is sufficient to take a look at Ideal Standard to see that the two questions are to be answered in the affirmative.

In Ideal Standard, the Court held that the assignment of a trade mark can amount to a cartel-like arrangement (more precisely, it can amount to market-sharing). In such circumstances, it would be restrictive by object. As in Generics, however, the Court was careful to point out that the issue cannot be ascertained in the abstract and requires a case-by-case, context-specific assessment.

What is ‘robust and reliable experience’? The example of the Special Advisers’ Report

While the Court made an express reference to ‘robust and reliable experience’, it never fleshed out the concept. Inevitably, it can be interpreted in a variety of ways. The most reasonable way to make sense of it is to read para 76 of Budapest Bank together with AG Bobek’s Opinion, which is explicitly cited in the judgment.

It would seem that the key question is whether a consensus has emerged about the nature, purpose and potential (pro- and anticompetitive effects) of a practice, and whether this consensus has found its way in the practice of courts and authorities. In this regard, the lessons from mainstream economics are of particular relevance.

The Special Advisers’ Report provide an example a contrario. The authors acknowledge that the efficiencies of certain practices in the digital economy are ‘not yet well understood our knowledge and understanding still needs to evolve step by step’. In such circumstances, it would be reasonable to conclude that the ‘by object’ label (or, more generally, their prima facie prohibition irrespective of their effects) would not be appropriate.

Court of Appeal in Ping: how market integration complicates the analysis of object restrictions

Market integration: why it matters in cases like Ping

Market integration considerations are essential to understand EU competition law. Articles 101 and 102 TFEU exist, after all, as part of a wider project that seeks to remove barriers to trade and create an internal market.

Thus, one cannot be surprised that, from the outset, market integration was treated differently under Article 101(1) TFEU. In Consten-Grundig, the Court expressed concern about the risk that firms recreate the very barriers that the Treaty sought to bring down.

How is the special status of market integration manifested in practice? In a stricter, treatment of practices aimed at restricting cross-border trade within the EU. The topic is dear to my heart and I discussed it in a number of papers and at this year’s GCLC conference (see here for the slides).

Earlier this month I commented on Budapest Bank (here) and, more generally, the principles of the case law (here). There is a long line of case law suggesting that, as soon as the Court finds a plausible pro-competitive rationale for an agreement, the ‘by object’ categorisation can be ruled out. Budapest Bank is valuable in that it states, in para 83, that ‘serious indicia’ about the pro-competitive effects of the agreement are conclusive in this regard.

The Court departs from these principles, alas, when market integration is at stake. It is, as I have explained elsewhere (for instance here), one of the outliers in the case law (and one for which I think there are good reasons: my own view is that the symbolic dimension of market integration would alone justify this stricter legal treatment).

Accordingly, conduct aimed at restricting cross-border trade (for instance, an export ban or absolute territorial protection) is in principle restrictive by object even if it is known to be a plausible source of efficiency gains (by the way: if you were wondering how paras 52 and 83 in Budapest Bank can be reconciled, this is, I believe, part of the answer).

If the parties to an agreement aimed at restricting cross-border trade want to avoid the ‘by object’ qualification they can, as the Court held in Murphy (para 140). However, they would have to overcome higher hurdles than usual. They would need to show either that the restraints are objectively necessary to achieve a pro-competitive aim or that they are not capable of restricting competition (which would for instance be the case if there were ‘insurmountable barriers’ to cross-border trade).

The legal analysis in Ping and the conspicuous absence of market integration

You may be wondering what the above may have to do with the Ping ruling of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, decided earlier this year.

The case involved a ban on online sales à la Pierre Fabre. Against the background of the above, the case seems straightforward. Online sales bans are problematic in EU competition law insofar as they limit passive sales. And limiting passive sales is, as recent action by the Commission since the e-commerce inquiry shows, inimical to market integration. The Internet is a most powerful tool to promote cross-border trade.

Accordingly, a ban on online sales is restrictive by object unless the parties can show that it is objectively necessary and/or it is incapable of restricting competition in its economic and legal context.

If you read the Court of Appeal ruling in Ping (as well as the CAT ruling and the CMA decision), you will realise two things: (i) the outcome is the same as above (the online sales ban is restrictive by object) and (ii) the reasoning is infinitely more convoluted.

The CMA, the CAT and the Court of Appeal all reached the same conclusion about the legal status of the ban. As the law stands, this conclusion seems uncontroversial. However, all three bodies struggled with a key aspect of the case: the online sales ban is at least plausibly pro-competitive.

If one reads the facts in both Ping and Pierre Fabre, it is difficult to avoid the impression that the ban was probably all about brand image and the creation of an aura of exclusivity and prestige around the products. Why, otherwise, would a firm want to limit the exposure, and thus the sales, of its products?

How to reconcile the fact that the ban is a plausible source of pro-competitive gains and its status as a restriction by object? Market integration, as seen above, provides the easy, straightforward answer.

Since market integration was never seriously considered in the analysis, the CMA, CAT and Court of Appeal could not avoid some legal contortions to reach the desired (and correct) outcome. The CMA went as far as to suggest that a restraint amounts to an object infringement unless it is objectively necessary (this position, at odds with the case law, was discussed on the blog here). The CAT, in turn, suggested that a plain vanilla cartel like the one in BIDS was plausibly pro-competitive (see here).

Finally, the Court of Appeal had to engage with AG Bobek’s Opinion in Budapest Bank, which summarised the relevant case law. Now that we have the judgment, it seems to me that the Court of Appeal departed from the Court’s interpretation of Article 101(1) TFEU in some important respects.

In particular, the Court of Appeal seems to require more than ‘serious indicia’ about the pro-competitive gains resulting from the agreement; in addition, it limited the scope of Cartes Bancaires as relating to two-sided markets alone (as opposed to pro-competitive gains more generally, which is the interpretation Generics and Budapest Bank would confirm).

Market integration and restrictions by object: more clarity needed

Market integration has enjoyed a special status in the EU system from the very early days. It is difficult to see that reality changing. More importantly, there is no reason why it should. Accordingly, clauses that would be typically unproblematic in other legal systems (including a post-Brexit UK?), such as online sales bans, are in principle restrictive by object.

The Ping judgment, on the other hand, suggests that it may perhaps be a good idea if some aspects about the special status of market integration were made explicit in the case law. This move would avoid the confusion of methodologies that we observe in the Court of Appeal ruling (and, as the example of Glaxo Spain case shows, this is not the first time we witness this situation).

Chillin’Competition’s Rubén Perea Award

Rubén Perea passed away on 1 April 2020 at 25 years old.

He was a smart, kind, formidable guy who had just completed his LL.M at the College of Europe and accepted an offer to work as a competition lawyer at Garrigues in Brussels. He bravely fought for months against cancer, a fight he ultimately could not win because the Covid-19 delayed the surgery on which we all had our hopes. The grace and courage he showed in these past few months revealed the kind of person that he was, that he would have been, and that we have tragically lost.

In his memory, we have decided to create the annual “Rubén Perea Award” for the best paper (master thesis, research paper or article) in competition/state aid law written by lawyers, economists or students under 30 years old.

The paper will be published in the Journal of European Competition Law and Practice. The winners will be announced on the blog, where they will have the opportunity to present their work in a guest post. If the circumstances allow it, an award will be presented at our next Chillin’Competition conference.

We call on university professors and senior lawyers or economists to encourage their students and younger colleagues to apply. The deadline for submission will be 15 September, so you can save the date. More details will follow soon.

We are also exploring the possibility of funding a scholarship to pursue EU studies in Ruben’s memory, and we hope to publish more info on this soon. Should anyone like to contribute to this initiative, please drop us a line.

On the possible ex ante regulation of online platforms (I): lessons from the EU telecoms regime

Before our world was turned upside down, a major theme in our community concerned the possibility of regulating ex ante online platforms. No matter how challenging the times, it is safe to predict that this question will not completely go away in the foreseeable future.

For the same reason, it makes sense to start a conversation about the possible ex ante regulation of online platforms, and more precisely about (i) why we would want it and (ii) what it would look like if it is ever going to see the light of day. Further posts will follow, as well as, hopefully, some sort of online discussion.

I would not break new ground by saying that it is an exercise that requires careful reflection. Any regulatory regime needs to be scrupulously crafted to ensure that the public interest is preserved. When there is so much at stake this is often a challenge. And claiming that something ‘needs to be done’ is not sufficiently compelling.

Fortunately, we have a template that gives us an idea of why and when to regulate online platforms. I see it as an insurance against sub-optimal outcomes. The EU telecoms regime (that is, the EU Regulatory Framework for electronic communications) asks the right questions and provides the right answers. Every time I look into it I realise that it is, in fact, an impressive achievement.

The EU telecoms regime has always been part of my research and teaching and thought it would be a good idea to start by discussing on the blog how a regulatory framework inspired in its approach would work, and whether there are good reasons to depart from the principles and approach enshrined in it.

Principles of regulation (and how they could apply to digital markets)

When the European Commission proposed the adoption of a new regulatory framework for electronic communications, it was aware of the challenge posed by innovation and technological evolution. Telecommunications activities were undergoing major changes; it was necessary to adapt regulation so that it would not become obsolete (that intervention would continue where it would no longer be necessary and/or it would be unable to address new issues).

The main principles of the framework can be summarised as follows:

- Flexibility and adaptability: legislation sets the objectives and the procedure to be followed by regulatory authorities; it does not directly prescribe the remedies.

- No regulation for the sake of regulation: the framework is premised on regulatory humility. Competition is seen as the best form of regulation, and as the default. Regulatory intervention only takes place where it can be shown that competition law would be unable to address the problem (mainly due to the problems that come with proactive remedies) and where there are major and lasting structural problems in a market.

- Technology neutrality: the framework was crafted to ensure that it would not favour a particular technology over others, and that the market, not regulation, would pick winners and losers.

- Bias against intervention in newly emerging markets: the framework is particularly careful not to intervene in nascent markets, where it is difficult, by definition to anticipate their evolution.

If ex ante regulation is ever adopted for online platforms, I hope the principles outlined above will also guide the regime. Two particular aspects deserve attention.

First, I cannot think of a good reason why an ex ante regime for platforms should not revolve around principles, as opposed to outcomes. In other words: it seems to me that ex ante regulation should provide for the objectives and the process through which the need for intervention is considered. By the same token, the details of intervention should be left to a regulatory authority. The temptation to enshrine particular remedies in legislation may be strong. Wisely, the EU legislature resisted it.

Second, it seems to me that neutrality should be a key guiding principle, in particular when (as acknowledged in the Special Advisers’ Report), there is much that we do not know about the gains resulting from practices in the digital sphere. There appears to be every reason to ensure that any ex ante regime does not have a built-in bias in favour of, or against, certain practices or business models.

The operation of the regime

As a principles-based regime, the EU telecoms regime leaves it to the regulatory authority to decide, on a regular basis, whether intervention is warranted and, if so, the remedies that may be needed to promote competition and innovation on a particular market segment.

How does the system work? If you are not familiar with the framework, you may not know that market definition (understood in the competition law sense) is central to the identification of regulatory concerns. The best explanation of when and why remedial action may be warranted is to be found, I think, in the Commission’s Explanatory Note on market definition.

The starting point of the analysis is to define, in accordance with competition law principles, a market on a segment that is potentially competitive and that is adjacent to a potential bottleneck. In telecoms, this adjacent segment could be, for instance, the one for retail broadband services (and the potential bottleneck the local loop).

In the digital sphere, this adjacent segment could be (I mention some examples that can be easily visualised) the online distribution of a particular good (say, books), a particular category of app (say, music), or a particular online service (say, travel). Each of these segments would relate to a particular bottleneck segment. Some good candidate markets that are less easy to visualise are extensively discussed in the CMA’s Interim Report.

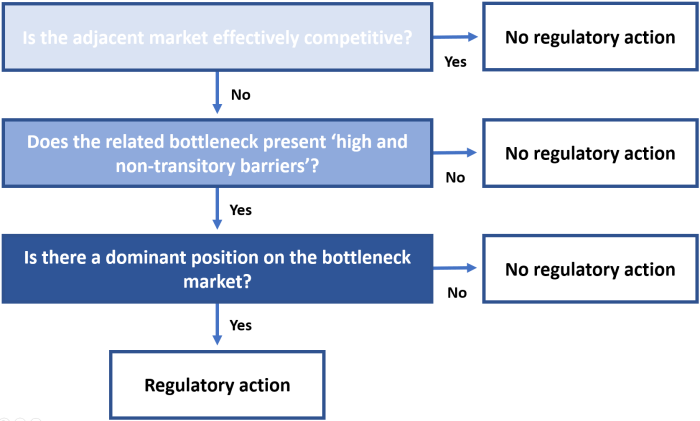

The key question is whether these adjacent segments are effectively competitive. If they turn out to be effectively competitive – in the sense that no dominant position can be identified – then regulation would not be warranted. No matter how strong the position of a market player on the potential bottleneck segment, no remedial action will take place (again, no regulation for the sake of regulation).

If they are not effectively competitive, then the two main questions that follow are, first, whether the potential bottleneck segment to which these activities relate has ‘high and non-transitory barriers to entry’ and, second, whether a dominant position can be established on this market. As part of this assessment, it would be necessary to consider whether this position is likely to last in the foreseeable future or whether, instead, technology and innovation would undermine this position (for instance, by allowing the firms on the adjacent segment to circumvent the bottleneck).

Only where these two questions are answered in the affirmative will the regulatory authority be in a position to impose remedies, which have to be adapted to the specific demands of every case (they range from transparency and/or non-discrimination obligations to the functional separation of some activities).

The operation of the EU telecoms regime provides two valuable lessons. Again, I cannot think of a good reason to deviate from them.

First, regulatory action should be based on a market-by-market assessment of the conditions of competition, not on a broad-brush identification of companies as having a ‘special status’ on the basis of vaguer, more general criteria. Second, where a market is effectively competitive absent intervention, regulatory obligations would not be warranted. In such circumstances, they can well do more harm than good.

As usual, your thoughts and comments would be most welcome.

Below you find, reduced to the essential, the logic of the framework.

Interim measures by the Autorité de la Concurrence: history repeats itself after IMS Health

Last week’s decision by the Autorité de la Concurrence is remarkable for several reasons, in particular because it provides for interim measures and it is about exploitative conduct. In that sense, it is an excellent example of what the new competition law will bring.

Traditional competition law was reluctant to engage with practices involving the administration of complex, prescriptive remedies (such as the redesign of a product or the determination of the terms and conditions under which firms are to deal with rivals and/or customers).

The decision reveals how much things are changing. As summarised in the picture above, the Autorité does not hesitate to mandate that Google set up a framework for its negotiations with press publishers and their remuneration.

At the same time, the decision feels like a déjà vu. When reading it, I could not avoid being reminded of the interim measures adopted by the Commission in IMS Health back in 2001 (and the subsequent developments before the then Court of First Instance).

As an instrument that invites us to ponder both the past and the future, it is a good starting point for a serene debate about the European competition law system and its evolution. Your thoughts and comments would, as usual, be most welcome.

Interim measures: IMS Health, Broadcom and Google

It is worth reading (or re-reading) the Order in IMS Health. As I understand it, there were two main reasons why the President of the CFI suspended the implementation of the interim measures decision in that case.

First, the Order explains that the Commission’s interpretation of the existing case law (in particular Magill) was, at best, controversial. Second, the President concluded that, rather than preserving the status quo (interim measures are known as mesures conservatoires for a reason), it sought to alter the market structure by means of proactive remedies changing the firm’s business model.

Following this experience, it would have been reasonable to anticipate that any new interim measures decision would be more risk averse than IMS Health. The European Commission’s decision in Broadcom (which concerned a well-established category of conduct, and involved a plain vanilla cease-and-desist obligation) comes across as the model of what one could have expected.

The Autorité’s decision shows that, contrary to this view, the days of ambitious action by means of interim measures, IMS Health-style, may not only not be over, but about to start.

Reasonable people can disagree about the legal analysis underpinning the decision. Whether or not the said analysis is correct is not the point. Instead, the fascinating issue – at least from the perspective of an independent academic – is that it breaks new ground, and does so by means of an unusual instrument.

At least in part, the assessment revolves around the idea that Google, when dealing with press publishers, has used its dominant position to frustrate the objective of the legislature, which was to allow press publishers to receive adequate remuneration for the exploitation of their sui generis rights. In this regard, Article 102 TFEU seems to be applied as a ‘safety net’ that assists and completes another area of economic regulation (a growing trend in contemporary enforcement).

A second, equally fascinating, point is that the interim measures decision only seems to make sense insofar as, and for as long as, Google displays protected content (one of the interim measures in fact requires the firm to keep displaying protected content).

Alas, copyright legislation merely provides for a right to authorise or prohibit the use of content. It is not a right to receive adequate remuneration (some rights are configured as such) and it does not provide for a right to have the said content displayed. In this sense, there seems to be a limit as to what the Autorité can achieve (at least under the theory of liability on which the decision is based).

As a result, the endgame is uncertain. Much depends, it seems, on how the various stakeholders react to intervention. I cannot avoid wondering whether the Autorité would go as far as to introduce a duty to display protected content. That would involve, again, breaking new ground, in more ways than one – but would also be consistent with the new competition law. An external observer could hardly ask for more.

Judicial review and the public interest

The Autorité’s decision exemplifies a key feature of the European competition law system. As I have been able to gather through my research, competition authorities in the EU are not paralysed by fear of judicial review. Unlike their US counterparts, they take risks when pursuing their policy objectives (which sometimes involves departing from the case law).

Inevitably, the higher the risk taken, the more likely it is to see a decision annulled by a review court. And such an outcome is a good thing and a positive indicator: I read somewhere, not long ago, that, if the rate of annulments is too low, it probably means that an authority is not doing its job properly. In this sense, I hope that the attitudes to judicial review will not change in the new environment (in spite of growing anxiety among some stakeholders, which I fully understand).

The public interest is advanced through the correction of errors of law and of fact and through the definition of the boundaries of the system. By the same token, the annulment of a decision is not a ‘blow’ or a ‘defeat’ (words I always disliked). It is not a sign of judges ‘not getting it’ or of existing doctrines being flawed and in need of change, either. It is, instead, the sound of the system working.

Generics vs Actavis: why the ‘by object’ and per se categories are different

As I was drafting, and thinking about, the past few posts, an idea kept coming back: the ‘by object’ category does not work like (and is very different from) per se restraints in US antitrust. Comparing the two (or presenting ‘by object’ infringements as the European version of per se prohibitions) is not accurate and can be misleading.

Some commentators like to turn to the US system and its categories (per se, ‘quick look’ and so on). to make sense of the EU law on restrictions by object. This is probably one of the reasons why there has been confusion about what the evaluation of the object of a practice entails under Article 101(1) TFEU.

If, instead of borrowing concepts from other legal systems, one reads the case law of the Court of Justice, it is easy to understand how different the two categories are.

Suffice it to compare Generics and Stephen Breyer’s Opinion in Actavis.

In Actavis, the majority agreed to examine reverse payment settlements under the rule of reason. In this sense, it went against the FTC’s position, which argued that such payments should be presumptively unlawful and subject to a ‘quick look’.

Justice Breyer explained in his opinion that the rule of reason is more appropriate as the likelihood of anticompetitive effects of this practice is very much context-dependent: the size of the reverse payment and, by the same token, the availability of justifications vary from one case to another. The majority concluded that the ‘quick look’ does not always fit all such practices.

In Generics, the Court ruled that it is necessary to evaluate, on a case-by-case basis, whether a reverse payment has an anticompetitive object in the economic and legal context of which it is a part.

The factors considered in the analysis are the same as those pondered by the US Supreme Court under the rule of reason: the size of the reverse payment and whether there is a plausible procompetitive rationale for it.

In this sense, there is an overlap between the two inquiries: the analysis at the ‘by object’ stage under Article 101(1) TFEU stretches to the point that it engages in a context-specific assessment of the nature of the practice. For the same reasons, it does not seem appropriate to draw analogies between ‘by object’ and per se.

To be sure, the purpose of the inquiry at the ‘by object’ stage and under the rule of reason is different. In Actavis, the point of the analysis is to evaluate the effects of the payment; in Generics, to make sense of the objective purpose of the practice.

In any event, I hope the bottomline is clear: the temptation to treat the ‘by object’ and per se categories may be strong, but it does not reflect the reality of what courts do and how they interpret the key provisions.

The case-by-case, context-specific approach to the identification of the most egregious infringements is a European specificity (and one that gets, in my view, the balance right).

Restrictions by object after Generics and Budapest Bank: a road map

It was relatively frequent to hear, until not so long ago, that it was not possible to discern, from the case law, a clear set of principles spelling out what a restriction of competition is. I have never been of this view (as explained here) but I understand where it was coming from.

The case law that followed the adoption of Regulation 1/2003 significantly clarified matters. Generics and Budapest Bank, the two most recent landmarks, provide the answers and the vocabulary we needed to present the Court’s interpretation of the notion of restriction by object in a systematic way.

Following the analysis of the said two judgments (I look forward to sharing some more thoughts on them in due course), I told myself it could be a good idea to draw a road map of the principles underpinning the case law and the way they have been applied by the Court over the years (there appears to be a clear and consistent trend dating back to the early days).

The road map is presented below and can also be downloaded here.

When evaluating whether an agreement amounts to a ‘by object’ infringement, two separate questions arise:

- First, what would an authority (or claimant) need to show to discharge its legal burden?

- Second, what sort of contrary evidence would the parties to the agreement need to adduce, and to what standard?

In relation to the first question, I understand the case law, as synthesised in Generics and Budapest Bank, as revolving around the following principles:

It was clear since Murphy that the parties may show that an agreement is not capable of restricting competition (and thus not restrictive, whether by object or effect). Generics and Budapest Bank confirm (and make it explicit) that the parties may also provide evidence, for the same purposes, showing that the agreement in question is capable of having a pro-competitive or ambivalent impact. More precisely:

Your comments and questions would be most welcome.

Case C-228/18, Budapest Bank: all the pieces are now in place (and we know what a restriction is)

The Court has just delivered another key ruling on restrictions of competition (see here for the French version). The judgment, just like AG Bobek’s Opinion in the case, is valuable in that it clarifies all the remaining controversies around the notion. The principles of the case law have been confirmed in an explicit way that does not seem to leave much scope for ambiguity. In addition, the judgment provides a template of how the analysis is to be conducted in practice.

The fundamental contributions of the judgment are the following (some of the points are explained at length below):

- The analysis of the counterfactual is relevant at the ‘by object’ stage (and the ‘by effect’ stage too): This question has been widely discussed (including in this blog) in recent years. While the case law was sufficiently clear already, Budapest Bank is valuable in that it provides a concrete example of how the counterfactual may be relevant to rule out that an agreement is restrictive by object or effect (and thus not caught by Article 101(1) TFEU). Paras 82 and 83 deserve particular attention in this regard (and they probably raise the single most relevant points of the judgment).

- The ‘by object’ category is only appropriate where there is sufficient experience about a practice: Budapest Bank fleshes out the contribution made in Cartes Bancaires. If there is no consensus about a practice (its nature, its pro- and anticompetitive effects), the Court explains, the ‘by object’ category is not appropriate.

- The analysis of the object of the agreement is a case-by-case, context-specific inquiry: It is not unusual to hear that the ‘by object’ category is a ‘shortcut’ aimed to make it easier and/or faster to establish restrictions. Budapest Bank shows that this characterisation does not reflect the reality of the case law. The inquiry is context-specific and makes it necessary to consider the peculiarities of the economic and legal context, and this in light of a series of indicators (including the counterfactual, the pro-competitive effects that the agreement is capable of achieving and the regulatory context).

- The objective purpose of the agreement needs to be effectively established: The judgment gives a clear answer to a key question: what if the agreement pursues two or more objectives simultaneously? What is the object of the agreement? What counts, the Court explains, are the objectives that are effectively established, not the objectives that are invoked (para 69). This is in line with Paroxetine.

Establishing the object of an agreement is a case-by-case, context-specific inquiry

It has become commonplace to characterise the ‘by object’ category as a ‘shortcut’. According to this view, it is sufficient to check whether the agreement is on the ‘list’ of ‘by object’ infringements to establish a restriction. Thus, it would be enough to take a ‘quick look’ to conclude that it is prima facie prohibited.

Budapest Bank shows that this characterisation of the case law (that seems to apply the logic of the US system to the EU legal order) has little to do with the way in which the ECJ conducts (and has always conducted) its analysis. The evaluation of the object of an agreement can be very detailed (the analysis of the question covers no fewer than 35 paragraphs) and can be as complex as showing that the same agreement has anticompetitive effects.

Accordingly, it is not sufficient to show that some clauses are suspicious (or that they are ‘on the list’). For instance, the Court explains that even an agreement that eliminates competition on a large fraction of the costs of two undertakings (or that sets a ceiling on the level of commissions to be paid) is not necessarily restrictive by object (paras 77 and 78).

Once again, the Court points out that the analysis is not complete without an evaluation of the relevant economic and legal context. The context is taken so seriously that, at several stages of the analysis, it explains that, without all the relevant information, it cannot come to a conclusion about whether the agreement has, as its object, the restriction of competition.

What sort of evidence is relevant at the ‘by object’ stage?

Unlike some judgments delivered in the context of a preliminary reference, Budapest Bank sets out in detail how the analysis is to be conducted in practice. The analysis complements Paroxetine very effectively.

In Paroxetine, the Court outlined what an authority needs to show to discharge its legal burden of proof: that the agreement has no plausible purpose other than the restriction of competition. Budapest Bank, in turn, is explicit about the sort of evidence that the parties may put forward to show that the agreement does not amount to a ‘by object’ infringement. The relevant factors in this regard are:

- Economic analysis: The parties may show, in light of formal economic analysis, that the object of the agreement is not anticompetitive. In this regard, Budapest Bank builds on Cartes Bancaires (which acknowledged that the two-sided nature of a market can shed light on the rationale of a practice).

- Experience (or, rather, the lack of experience): In Budapest Bank, the Court holds that the ‘by object’ category is only appropriate where there is robust and reliable (‘solide et fiable’) experience about the nature of the agreement (para 76). In this sense, the Court suggests that there should be a consensus about the status of the practice (see also para 79). Absent a consensus, the analysis of its effects becomes necessary.

- The pro-competitive effects of the agreeement: Paroxetine (in line with AG Bobek and Kokott) made it clear that the pro-competitive effects of an agreement are relevant as part of the evaluation of the economic and legal context. Budapest Bank confirms this point. Thus, the idea that these effects can only be considered under Article 101(3) TFEU can finally be put to rest. The pro-competitive dimension is also a factor when ascertaining whether there is a restriction in the first place (para 82).

- The counterfactual: Even if it was implicit in the preceding case law, it is useful to see the Court explain how the counterfactual (that is, the conditions of competition that would have existed in the absence of the agreement) can be considered. The parties claimed that the agreement was not restrictive by object because, in its absence, the conditions of competition would have been worse. The Court clarifies that evidence in this sense is acceptable (paras 82-83). It makes sense to copy these two paragraphs below[1] (in French for the moment). If there was any doubt, the Court also points out that the counterfactual is also relevant at the ‘by effect’ stage (see, in addition to para 82, paras 55 and 75).

Paragraphs 82 and 83 also show that the applicable threshold is one of plausibility (as suggested in Paroxetine too). It would be enough for the parties to establish that there are, a priori, serious indications that the agreement is capable of improving the conditions of competition that would otherwise have existed. If the evidence meets this threshold, the agreement is not restrictive by object and an analysis of effects is necessary.

A Moment of Truth for the EU: A Proposal for a State Aid Solidarity Fund

(By Alfonso Lamadrid de Pablo and José Luis Buendía)

The Covid-19 outbreak is putting societies, institutions, companies, families and individuals to the test. Like all major crises, it is exposing our strengths and weaknesses, our contradictions and limitations. A common threat of unprecedented scale has revealed, once again, that our societies are capable of the very best and the very worst. Over the past few days, we have witnessed inspiring examples of empathy and solidarity, but also prejudice, frustration and tension. We have the chance to show we are up to the task. How we collectively choose to react to this crisis will define our future.

Like all major crises, the Covid-19 outbreak is also straining the European Union, bringing once again unresolved tensions between Member States to the surface, and awakening dangerous currents of misunderstanding among citizens. Critics of EU integration have jumped on the occasion, failing to realize that the problem calls for more, not less EU. At the current stage of European integration, absent a fiscal union and with limited EU competences on public health, decisions remain mainly in the hands of national governments controlled by national Parliaments. Disagreements among EU Member States within the European Council are sometimes desirable, and sometimes not so much, but they are perhaps inevitable. It is not only a matter of attitude and prejudice, but also of institutional and political constraints. While we wait for consensus among national governments on a comprehensive political response, other constructive and complementary solutions must be explored.

The European Commission can be the driving force in the pursuit of EU solidarity. Unlike national governments, the Commission is entrusted with safeguarding the general interests of the Union as a whole. President von der Leyen has committed to exploring any options available within the limits of the Treaties. The Commission has both the responsibility and the power to take decisive action, and to shape the reactions of Member States to the crisis in line with the general interest. The Commission cannot require Member States to ignore or work around existing constraints, but it can impose proportionate ones.

Indeed, while the Commission’s powers may be limited in certain areas, they are strong and decisive in others. Notably, the Commission enjoys the exclusive competence to control, under State aid rules, the measures adopted by Member States to support economic operators. Over the past few days, the Commission has made a significant effort to exercise these powers swiftly and responsibly, adopting a Temporary Framework and authorizing a considerable number of national measures to support the economy in the context of the pandemic. As we write, the Commission has announced an imminent amendment to the Temporary Framework aimed at enlarging the categories of permitted aid.

The unquestionable necessity of allowing the speedy authorization of Covid-19-related national measures should, however, not blind us to their inevitable negative side-effects. The “full flexibility” recognized by the Temporary Framework applies in theory to all Member States. In practice, however, it mostly benefits deeper-pocketed Member States with the means and the budget to spend the greatest resources. Note that the Member States that benefit disproportionately from this policy are also the champions of austerity Member States that, rightly or wrongly, oppose other solidarity instruments like corona bonds. Under the current Temporary Framework, all Member States enjoy the same freedom to unleash their economic arsenal, but some may end up using bazookas, while others are stuck using slingshots.

Massive capital injections by only certain Member States might lead to massive distortions of competition. Companies and sectors from wealthy Member States may enjoy much more support to weather the crisis than their competitors established elsewhere in the EU, regardless of where the ongoing crisis happens to hit harder. Under the current circumstances, this could trigger the market exit of companies that would have normally survived, and vice versa. Competitive asymmetries deriving from State aid would moreover be exacerbated should national governments fail to reach an agreement on mutualizing budget risks.

This scenario is not inevitable. It is within the power of the European Commission to ensure sure that State aid is awarded in a way that minimizes any distortions of competition and, by the same token, fosters EU solidarity. The Commission itself recognizes in the Temporary Framework that a coordinated effort will make the measures adopted more effective and may even foster a quicker recovery. The Framework also emphasizes that this is not the time for a harmful subsidies race.

Our proposal is that the Commission amend the Temporary Framework in order to make the compatibility of State aid conditional on the provision of compensation for the competitive distortions that they necessarily create. This compensation would take the form of a contribution to the support of companies established in other Member States. The contribution could be equivalent to a percentage (for example, 15%) of the public resources involved in the measures at issue. Each Member State would be able to propose specific ways to channel these contributions in a way that minimizes competitive distortions. The Commission would assess their sufficiency prior to authorizing the aid, and it would also ensure that most of the compensation is received by those who need it the most.

In order to speed up the approval process, the Commission could also predetermine ex ante that contributions to a “European Solidarity Fund” would be presumed an acceptable compensation in this regard. The Fund could be initially established by some Member States as a vehicle allowing financial solidarity among them, but would be open all Member States. The Fund itself should also be notified under State aid rules and could obtain Commission approval as an “Important Project of Common European Interest” (IPCEI).

We see no EU law impediment to implementing this proposal. Making the compatibility of State aid measures subject to compensatory conditions would not in itself entail any deviation from the Commission’s standard assessment. The rules adopted by the Commission to manage the support to financial institutions in the context of the past crisis were accompanied by strict conditions aimed at minimizing distortions of trade and competition. To be sure, while requiring direct compensation from the State which granted the aid would constitute a novelty, this innovation would be justified. Indeed, the current circumstances do not permit the use of traditional safeguards, based on limiting the amounts of aid granted.

Several national measures have already been authorized, but it is not too late to take action. Public support measures are here to stay and are likely to materialize in unprecedented volumes of aid. Failure to prevent further asymmetries would only make matters worse. Under this proposal, Member States would retain the ability to support their national economies, subject only to the condition that they contribute, proportionately to their means and to their measures, to minimizing distortions to the internal market. This way, State aid policy could better contribute to the solution, rather than the problem.

Important details should be ironed out following an urgent consultation with Member States. Some version of this formula would not only be sensible and feasible, but also indispensable. It would mitigate serious distortions and contribute to levelling the playing field. In the absence of a political agreement between Member States, it would create a proportionate legal obligation to prevent harm to companies established in other EU countries, easing ‘rich’ Member States’ task of justifying their solidarity efforts to their citizens and parliaments. It would show precisely what the European Union is for and would restore citizens’ trust in the ideals of European integration. Let us not forget that, as empathically stated in Article 3 of the TEU, one of the main tasks of the EU is to promote ‘economic, social and territorial cohesion, and solidarity among Member States’.

This proposal is not a silver-bullet, but it is an important step towards solidarity based on legal mechanisms. As proclaimed in the Schuman declaration, the EU “will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity.” The European Commission has now the opportunity, the unique ability, and the historical responsibility to fulfill its mission.