Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

GCR LIVE- Law Leaders Europe (9-10 July 2024)

Global Competition Review will be hosting the 2024 edition of its Law Leaders Europe conference in Brussels on Tuesday 9 and Wednesday 10 July. Pablo and Director General Olivier Guersent will be the keynote speakers, and I will be co-chairing the conference together with Ethel Fonseca (RBB), Andrea Gomes da Silva (Fingleton) and Thomas Janssens (Freshfields).

Over two days, the conference will cover pretty much all significant recent (and expected) developments in the competition law field. The full, and pretty impressive, list of speakers is available here.

The program and all other relevant info are also available here.

Key takeaways from the Servier saga: object, (pro and anticompetitive) effects and counterfactual (II)

Yesterday’s post addressed the way in which the Servier saga (see in particular Case C‑176/19 P and Case C‑151/19 P) refined and clarified the interpretation of what amounts to a ‘by object’ infringement.

The saga also sheds light on the analytical framework that applies to the assessment of anticompetitive effects under Article 101(1) TFEU (the ‘by effect’ stage, if one prefers).

First, the judgments (in particular the one in Case C‑151/19 P) confirm that the divide between actual and potential effects refers to the temporal dimension of the analysis. In other words, the notion of actual has to do with with the observable impact of a practice (what actually occurred). Contrary to what is sometimes suggested, this term does not imply a higher threshold (relative to ‘potential effects’).

The threshold of effects remains the same, whether we consider actual or potential effects. What changes (and paras 313-335 in Case C‑151/19 P are a good illustration) is that in the latter case the analysis is prospective (potential) and in the former it is retrospective (actual).

Second, actual effects may be taken into consideration in the overall assessment even when the analysis is prospective. As the Court put in in para 321 in Case C‑151/19 P: ‘events subsequent to the conclusion of that agreement may be taken into account in order to assess that situation‘.

When the actual operation of the market can be observed, this evidence may shed light on the potential of the practice to harm competition (even if it is not conclusive). The Court’s position is also in line with that expressed in Servizio Elettrico Nazionale (para 54 of Case C-377/20).

Third, the purpose of the counterfactual is to determine whether there is a causal link between the practice and any actual or potential effects (para 317 in Case C‑151/19 P: ‘The purpose of that “counterfactual” method is to identify, in the context of the application of Article 101(1) TFEU, the existence of a causal link between, on the one hand, an agreement between undertakings and, on the other, the structure or functioning of competition on the market within which that agreement produces its effects […]’).

In other words, it is only possible to conclude that effects are attributable to a given behaviour by measuring them against the relevant countefactual (that is, the ‘but for’ scenario revealing how the market would have evolved in the absence of the practice).

As the Court puts it, the counterfactual ‘[…] makes it possible to ensure that characterisation as a restriction of competition by effect is reserved for agreements displaying not a mere correlation to a deterioration in the competitive situation of that market, but for those agreements that are the cause of that deterioration‘ (ibid; emphasis added).

The points above are not strictly new, but are valuable, to begin with, because of the structure the Court provides and the careful drafting. It is a clear and effective articulation of the role of the counterfactual in the analysis of effects and in establishing causality.

It is also valuable in that it is line with Advocate General Kokott’s Opinion in Google Shopping. As explained here, she pointed out (para 172 of the Opinion) that the issue of the counterfactual must not be conflated with the temporal dimension of the analysis.

The Servier saga proves Advocate General Kokott’s point. It illustrates, in concrete terms, that the counterfactual is also relevant when evaluating whether the alleged potential effects of a practice are indeed attributable to it.

Key takeaways from the Servier saga: object, (pro and anticompetitive) effects and counterfactual (I)

Last Thursday, the Court of Justice delivered its judgments in the Servier saga (see in particular Case C‑176/19 P and Case C‑151/19 P). These rulings will become an inescapable reference when discussing the notion of restriction of competition. They confirm some trends in the case law, refine some aspects thereof and provide a clear analytical framework.

First, the core test to evaluate whether an agreement restricts competition by object remains unchanged relative to Generics. Accordingly, it is necessary for an authority or claimant to identify the explanation for, or rationale behind, the practice (that is, its object).

In the specific context of the Servier saga, the analysis revolved around ‘whether [the] transfers of value can have no explanation other than the commercial interest of those manufacturers of medicinal products not to engage in competition on the merits‘ (see for instance para 104 of Case C-176/19 P; emphasis added).

Second, an infringement within the meaning of Article 101(1) TFEU, whether by object or effect, can only be established if there is competition to restrict in the first place. Thus, there would be no collusive market sharing where the regulatory context makes competition between the undertakings impossible (where, in other words, they are not actual or potential competitors).

The analytical framework in Servier is important in two respects. In the first place, the question of whether there is competition to restrict in the first place is presented by the Court an integral aspect of the evaluation of the object of a practice (it is identified as the first stage of the analysis; see paras 99-100 of Case C-176/19 P).

In the second place, it is now clear that, where there is no (inter-brand or intra-brand) competition to restrict, the agreement cannot be inherently anticompetitive.

My only comment in this regard is that the careful analytical framework laid down by the Court suggests that there is an additional stage. Before going into whether there is actual or potential competition, the ruling identifies, as a preliminary stage, the ‘candidate object‘ of the practice (that is, the reason why the agreement may have, as its object, the restriction of competition).

In the Servier saga, the ‘candidate object’ was collusive market sharing. The analysis that followed aimed at establishing whether the suspicion of a ‘by object’ infringement via collusion was borne out by the evidence.

Third, a restriction by object cannot be identified in the abstract. It has long been clear that a practice can only be shown to be inherenly anticompetitive by paying attention to the economic and legal context. The Servier saga is useful in that it shows that this principle works both ways: it applies both to the authority (or claimant) and the parties to the agreeement.

Just like authorities cannot categorise a practice as restrictive by object on the basis of abstract considerations, undertakings cannot escape the prohibition simply because, generally speaking, their agreement is not a suspicious one. For instance, it is irrelevant that, as a rule, settlement agreements do not have a restrictive object and are not inherently sinister (para 395 of Case C‑151/19 P).

In the same vein, the formal features of an agreement are insufficient to escape the prohibition (again, just like they are insufficient to establish one; see also para 395 of Case C‑151/19 P). In line with its consistent approach over decades, the Court placed substance above form in the saga.

Fourt, the pro-competitive and anticompetitive effects of a practice are neither necessary nor relevant to prove that it has a restrictive object. This is a point where the Court refines its case law, and confirms what was announced in Superleague.

Thus, the doctrine introduced in Generics, whereby the pro-competitive effects of an agreement may be taken into consideration when evaluating the relevant economic and legal context, is abandoned.

This refinement of the case law is not difficult to rationalise. When confronted with the reality of the doctrine, the Court may have realised that it is impossible to manage and that it might empty the ‘by object’ category of its substance.

In the early days, the Court feared an overly expansive understanding of the notion of ‘by object’ infringement. The abandonment of the Generics doctrine appears to reflect the opposite concern, insofar as taking into account the pro-competitive impact of a practice may inevitably blur the line between object and effect (this concern has been expressed by Advocates General in their Opinions).

One should point out, in any event, that this refinement is a relatively minor one. The real question, at the ‘by object’ stage, has always been whether the explanation for the agreement is a restrictive one (or a non-restrictive one instead), not whether it has positive effects on competition.

Crucially, the Court is equally emphatic about the fact that the anticompetitive effects of the agreement are not relevant at the by object stage. This point is particularly important in the wake of Advocate General Szpunar’s Opinion in FIFA v BZ (which relied exclusively on the impact of a set of rules to conclude that their object was anticompetitive).

Announcing the 5th edition of the Rubén Perea Writing Award

Our friend and colleague Rubén Perea Molleda passed away five years ago just when he was about to start a promising career in competition law following his graduation from the College of Europe. Rubén remains very present in the memory of everyone who had the chance to cross paths with him. In his memory, we created a competition law writing award. Today we are launching its 5th edition.

As in previous editions, the winning paper will be published in a special issue of the Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, together with a selection of the best submissions received (the JECLAP special issue featuring the winner and finalists of the 4th edition will be out very soon; the articles are already available as a pre-publication).

Who can participate?

You may participate if you remain below the age of 30 by the submission date (i.e., if you were born after 15 October 1994). Undergraduate and postgraduate students, as well as scholars, public officials and practitioners are all invited to participate.

What papers can be submitted?

You may submit a single-author unpublished paper which is not under consideration elsewhere. The paper may be specifically prepared for the award or originally drafted as an undergraduate or postgraduate dissertation or paper.

The paper must not exceed 15,000 words (footnotes included; no bibliography needed).

Prior to submission, please make sure your paper follows the JECLAP House Style rules, which can be found here.

How to submit?

Please submit the paper via this link: https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jeclap.

IMPORTANT: As you go through the submission process, make sure that in Step 5, you answer YES to the question “Is this for a special issue?”, and indicate that your submission relates to the Rubén Perea Award.

What is the DEADLINE?

Papers have to be submitted by 23.59 (Brussels time) on 15 October 2024.

REGISTER for the 1st Chillin’ Live Podcast: 27st June (16.00 London time/17.00 Brussels time)

Many of you have approached us in the past few months asking whether we had considered launching a podcast. Since it is a great idea, we thought we would give it a tentative go. Alfonso will be coming over to LSE Law School on 27st June (Thursday of next week). We will be starting the live podcast at 16.00 London time/17.00 Brussels time. The recording will be made available later.

Make sure you save the date! For this first live podcast, we will build our discussion around a forthcoming paper of mine, which deals with the notion of restriction by object (entitled ‘Restrictions by object under Article 101(1) TFEU: from dark art to administrable framework‘).

We have been talking about restrictions by object for the best part of two decades, and the time feels right to present, in a structured manner, the contributions made by the Court, including the clarifications provided in recent rulings like Superleague (if you were wondering, the paper concludes that the case law provides the basis for an analytical framework that is both administrable and predictable).

If you would like to join (online) the live Zoom seminar, feel free to register here. Once you register, you will receive an email that will allow you to access the livestream on the 27th.

I will be sharing the article in the coming days, so we can have a proper discussion during the Q&A. Do not hesitate to get in touch with any questions, comments or suggestions. We look forward to meeting many of you on the day (albeit virtually)!

Heike Schweitzer (1968-2024)

Professor Heike Schweitzer, one of Europe’s most prominent and influential competition law scholars, passed away earlier this week. She has left an indelible mark in law and policy discussions as a mentor to generations of students and a frequent adviser to agencies and governments.

Those of us who were fortunate enough to work with, and learn from, her will miss Heike dearly. At the same time, she will very much remain a presence in our lives.

I would frequently share my thoughts with Heike (I recently wrote that every conversation with her is memorable). Even when I did not, her critical eye was the benchmark against which I assessed the quality of my work. ‘What would Heike think?’ has been a guide since we first met back in 2006. I do not see how this will ever change.

The qualities for which she will be remembered are obvious to anyone who spent more than five minutes with her. The first thing that comes to mind is the natural authority she displayed, unassumingly, in any conversation. It came from her in-depth knowledge and her ability to spot the crucial issue in any discussion (all of that peppered, as I learnt over time, with her sense of humour and quick wit).

Heike’s intellect and clarity of thought allowed her to engage meaningfully with scholars and professionals from a wide variety of persuasions. Her convictions and ideas never stood in the way of a respectful exchange of views. Those of us who were fortunate enough to study under her supervision benefitted immensely from these virtues: we always felt we would get to write our own thesis, not somebody else’s.

Any portrait of Heike would be incomplete without mentioning her generosity. Many will point out how hard-working she was. She was precisely because of how much she gave back to the community.

Her appointment as a Special Adviser to Commissioner Vestager on digital competition policy or her crucial contribution to Germany’s foremost competition law treatise are just two of many examples. As an academic at heart, however, Heike’s students always were the primary beneficiaries of her generous spirit.

May she rest in peace.

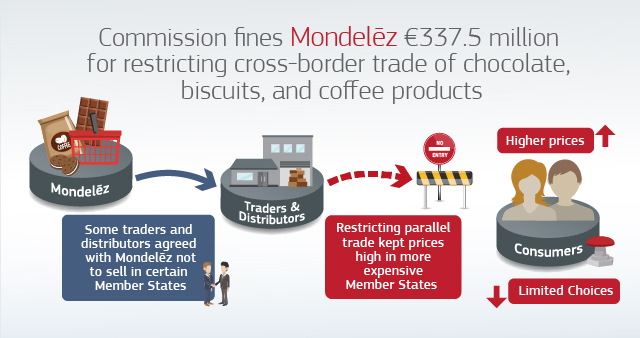

Mondelez: abuses by object, consistency and the administrability of Article 102 TFEU

Last week, the Commission announced that it has fined Mondelez for engaging in a series of practices aimed at restricting intra-EU trade. There is nothing new or special about Mondelez’s conduct.

The decision comprises bread-and-butter cross-border limitations (which have always been sanctioned as restrictive by their very nature under Article 101 TFEU) and unilateral conduct with the very same object. The latter included the refusal to sale a product to a broker and the decision to cease supplies. Both have been found to amount to an abuse of a dominant position.

The above does not mean that the decision is uninteresting. It is, but for a different reason. We have seen much talk, in the context of the ongoing review of Article 102 TFEU enforcement, about ‘by object’ abuses and, more generally, about whether it is necessary to show anticompetitive effects in relation to every potentially abusive practice.

The Mondelez case provides, against this background, two examples of practices that are deemed abusive without the need to establish their restrictive impact in the relevant economic and legal context. As is clear from the press release, this is so because their very object is to restrict intra-EU trade (and as such inherently anticompetitive in the EU legal order).

As explained earlier this year, the Court of Justice demands that Articles 101 and 102 TFEU be interpreted consistently. If restrictions to intra-EU trade are, in principle, restrictive by object under the former, it is only logical that they are treated in the same way under Article 102 TFEU. I, for one, look forward to reading the decision and finding out how the Commission goes about the question.

Mondelez is interesting for another reason. It reveals that the Intel doctrine (whereby dominant the firms have the chance to show that a practice is incapable of restricting competition) will sometimes prove plain ineffective from the perspective of a dominant firm. By the same token, there will be instances where any claims about the lack of effects can be summarily dismissed by an authority.

It would be wrong to assume, in other words, that Intel requires an authority to engage in analysis of effects in every instance. For the same reason, it would be wrong to present the doctrine as an obstacle to the administrability of Article 102 TFEU. The more egregious the infringement, the more limited the relevance of Intel and the less likely the need to engage in an analysis of effects.

Conduct aimed at limiting intra-EU trade (the quintessential example of egregious conduct, alongside cartels) is only incapable of restricting competition in very limited instances, namely (i) where the absence of cross-border trade is attributable to the regulatory context, not to the practice; and (ii) where allowing such trade would empty an intellectual property right of its substance (as in Erauw-Jacquery).

The extent to which arguments of this kind have limited traction when intra-EU trade is at stake became apparent in the Valve case, discussed here. That case related to the application of Article 101 TFEU, but the insights would be relevant, almost word for word, in the context of Article 102 TFEU.

As I say, one decision to look forward to reading.

Opinion of AG Szpunar in Case C‑650/22, FIFA v BZ: restrictions by object and the regulation of joint ventures through Article 101 TFEU

AG Szpunar Opinion in FIFA v BZ was delivered yesterday. The opinion is remarkable, from the perspective of an EU competition lawyer, for several reasons.

It stands out, first, because of how categorical the Advocate General is when interpeting the law. It is unusual that, in the context of a preliminary reference, an Opinion states unambiguously that a practice amounts to a restriction of competition by object and that, in addition, it does not meet the conditions set out in Article 101(3) TFEU.

In principle, it is for the referring court (which has all the necessary information) to apply EU law to the facts of the case.

The Opinion is also remarkable because of how it approaches the question of whether the rules at stake have, as their object, the restriction of competition. Anyone familiar with the relevant case law will realise that the methodology chosen by AG Szpunar departs from the principles laid down in Cartes Bancaires and the judgments that followed.

The preliminary reference submitted by the Cour d’appel de Mons concerned some aspects of FIFA’s Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (‘RSTP’). These rules foresaw a system of sanctions (in addition to compensation) applicable to the clubs that sign players that have terminated the contract without just cause.

In essence, the regulations seek to disincentivise the signing of players that are in breach of their contractual duties and they also seek to disincentive some aggressive practices by clubs (the latter may feel tempted to induce players to terminate their contracts abruptly).

Do these rules have, as their object, the restriction of competition? The abovementioned case law makes it clear than an answer to this question must consider the content of the rules, their aim and the economic and legal context of which they are a part.

According to the Opinion, the European Commission had taken the view, in its submission, that the relevant provisions of the RSTP were not anticompetitive by their very nature. It is not difficult to see how the Commission might have reached this conclusion.

One could plausibly argue that the purpose of the system of sanctions at stake in the case is to prevent the sort of buccaneering conduct that could negatively affect the integrity of competitions and could easily escalate (and would typically benefit wealthier clubs). If that is the case, the object of the regulations would not be the restriction of competition, but a different one.

It is imperative to bear in mind, in this regard, that clubs taking part in organised sports are not mere competitors (and thus not competitors in the usual sense). They cooperate as much as they compete, and cooperation involves, by necessity, restricting their freedom of action at least to some extent so that their common objectives can be attained.

AG Szpunar did not take into account these factors, which are key to make sense of the relevant economic and legal context. Instead of relying on the criteria laid down in the case law, the Opinion focuses on the impact of the rules.

More precisely (para 53), the Advocate General sees the ‘consequences’ of a termination without cause as ‘draconian’. In the same vein, he argues that the rules are designed to have a ‘deterrent effect’.

By focusing on the consequences of a breach, the Opinion infers an anticompetitive object from the effects of the rules. In other words, AG Szpunar relies on their impact to conclude that they are restrictive by their very nature.

By blurring the line between object and effect, the Opinion embraces a methodological approach that departs from the one laid down in the case law.

Under the methodology consistently followed by the Court, the question is not whether the relevant regulations have a deterrent effect (which they undeniably do). The question, instead, is what the object of this deterrent is.

If it turns out that the disincentive pursues an aim that is not anticompetitive, then it is not prohibited as a restriction by object (but could well have, as the European Commission argued in this case, restrictive effects).

And the experience of decades shows that, in the context of cooperative joint ventures (such as organised football), these disincentives often do not have an inherently restrictive object, but one that ensures the adequate functioning of the co-opetitive arrangement (Cartes Bancaires is an example that comes to mind again; Gøttrup-Klim is another one).

The reference to cooperative joint ventures takes me to the third reason why the Opinion is remarkable. By adopting an expansive interpretation of the notion of ‘by object’ infringement, Advocate General Szpunar sees competition law as a discipline that has a frequent and proactive role to play in the regulation of such ventures.

This position would have involve a major departure from the position that the Court has taken so far. After all, Wouters was an acknowledgement that Article 101 TFEU is ill-suited to second-guess the decisions taken by governance bodies on co-opetitive structures and thus will only intervene in exceptional circumstances.

The trio of judgments issued last December did not fundamentally change this balance. As I explained here, these judgments only interfere at the margins with governing bodies.

This long-standing position would change fundamentally if the scope for the application of the Wouters doctrine were significantly reduced (as would be the case if the notion of restriction by object where interpreted in the way suggested by AG Szpunar).

(As ever, I have nothing to disclose).

The New EU Competition Law on tour: Madrid, 28 May (at the CNMC)

I am delighted to announce that the Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia will host an event around The New EU Competition Law on 28th May (the reception will start at around 3.30pm and the event as such, at 4.30pm).

You can register for it here.

Presenting the book in my hometown, and at the competition authority, will be a highlight of the book tour. I am really grateful to the staff at the CNMC for making it happen. I am also grateful to the speakers who have managed to make some time for the occasion:

Cani Fernández, President of the CNMC, will deliver the opening address at 4.30pm.

Her speech will be followed by a round table discussion with Beatriz de Guindos (AECID), Javier García-Verdugo (CNMC) and Alfonso Lamadrid (Garrigues and, to be sure, Chillin’).

Marisa Tierno, Director for Competition at the CNMC, will share some thoughts at the end.

If you happen to be in Madrid on the day, please pass by!

CALL FOR ABSTRACTS | JECLAP Special Issue on EU merger control

The Journal of European Competition Law & Practice (of which I am the Joint General Editor with Gianni De Stefano) is proud to announce that it will be publishing, later this year, a Special Issue devoted to EU merger control (and the changes it is undergoing).

Major developments are taking place on every front, from the jurisdictional to the substantive. We would be delighted to consider proposals on any major topic, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Market definition, and the impact of the recent Commission notice on the field.

- The application of Article 102 TFEU to merger control following the Towercast judgment.

- The meaning and scope of Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation.

- Ecosystem theories of harm in the wake of Booking/eTraveli.

- Remedies in EU merger control.

- 20 years of the ‘oligopoly gap‘: where do we stand after the appeal in CK Telecoms?

- Judicial review in EU merger control.

- Interaction between EU merger control and other systems.

If you have an idea for a paper, please email Gianni (Gianni.De-Stefano@ec.europa.eu) and/or myself (P.Ibanez-Colomo@lse.ac.uk) by Friday of next week (3 May) with your proposal.

This proposal should take the form of an abstract of max. 250 words in which you outline:

- The issue you would like to address;

- The angle you intend to take;

- The contribution your piece is expected to make; and

- Whether you have any actual or potential conflicts of interest.

If your abstract is accepted (we will let you know immediately), we expect the final article (of around 7,000-10,000 words) to be submitted by mid-June at the latest.

We will select abstracts to maximise diversity and balance in the Special Issue. We are, as ever, keen to give a voice to new authors and different approaches. If there was any doubt: we welcome legal and economic perspectives (and, to be sure, papers that combine both).

In the meantime, do not hesitate to get in touch with any questions or suggestions!