JOB OPENING: want to join LSE Law School as an Assistant Professor of Competition Law?

LSE Law School is looking for an Assistant Professor of Competition Law, to join the Faculty in September 2026. All information in terms of requirements, conditions and on how to apply can be found here: https://www.jobs.ac.uk/job/DOZ822/assistant-professor-in-law-competition-law.

Needless to say, the competition law team could not be more excited about the prospect of enhancing our teaching and research capabilities in the field.

I can tell from experience that LSE Law School is a non-hierarchical environment that allows you to flourish and find your voice as a scholar. Teaching and administrative duties are light in the first few years (up until promotion to an Associate Professorship). In addition, you will benefit from an annual (and generous) research allowance.

You may be asked to contribute to teaching in foundational subjects, but our competition law curriculum is large and varied. In addition to a dedicated undergraduate module, the LSE Law School now offers an LLM programme with an ample array of competition law options, ranging from State aid and subsidies to the regulation of competition in digital markets.

If you are interested in applying and would like to have an informal chat about the post, do not hesitate to get in touch with me.

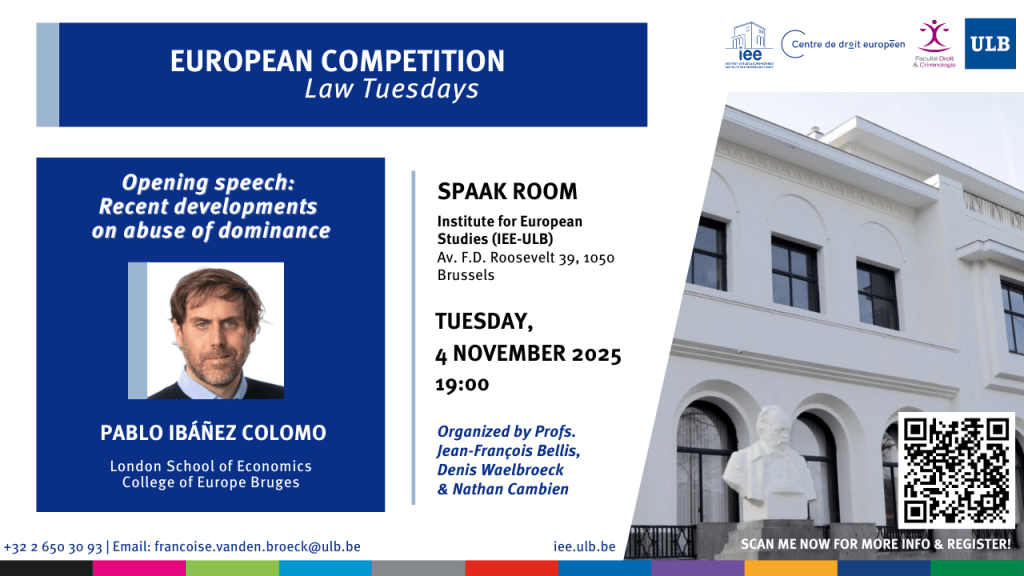

SAVE THE DATE: Recent developments on abuse of dominance (Brussels, 4th November at IEE-ULB)

With every new academic year comes a new edition of the mardis du droit de la concurrence, This series has been around pretty muchsince the dawn of European competition law. It continues to be a unique venue to get a sense of the evolution and direction of travel of our field, more recently under the expert leadership of Denis Waelbroeck and Jean-François Bellis (now joined by the great Nathan Cambien).

The programme for the new academic year is now out (see here). It includes talks that have become classic fixtures, such as Fernando Castillo de la Torre‘s overview of the case law in the area of cartels and provides a complete tour d’horizon of all areas of enforcement, featuring both Commission officials and private practitioners.

Advocate General Laila Medina will be closing this year’s series with a *lundi du droit* (11th May 2026) with a speech on ‘EU competition law and the Court of Justice‘.

I am honoured (and grateful) to have been invited to open this year’s series on Tuesday 4th November (7pm Brussels time) with a discussion on the recent developments on abuse of dominance. More info on can be found on the flyer above. I really look forward to seeing many of you there!

COMING SOON: The New Law of State Aid and Subsidies (Hart Publishing)

This blog has been neglected to such an extent in the past few months that some of you got in touch to ask whether everything was OK. Fortunately, the only reason I did not get around to sharing thoughts more often is that I was absorbed in the writing of The New Law of State Aid and Subsidies.

As the very cover suggests, it is the second volume of ‘The New’ trilogy, the first instalment of which was The New EU Competition Law. If you were wondering, I hope it will be followed by a monograph on merger control, which is also undergoing fundamental transformations.

I submitted the manuscript to Hart in the early days of summer, and The New Law of State Aid and Subsidies already has a dedicated webpage: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/new-law-of-state-aid-and-subsidies-9781509990306/.

The new instalment of the trilogy shares the philosophy of the preceding one: a relatively short, affordable (it will come out in paperback from the beginning) and hopefully accessible volume that is modular by design (in the sense that individual chapters can be read independently of one another).

This is a book that I have been meaning to write for a long time. In more ways than one, it is the fruit of many years teaching State aid and subsidies at the LSE Law School. Providing a conceptual framework to convey the essence of the discipline to students approaching it for the first time is a real challenge. Some chapters (such as the one devoted to selectivity) reflect many hours of class discussions and are no doubt enriched by students’ contributions.

Other chapters seek to trace the various ways in which the law of State aid and subsidies is undergoing fundamental changes. There are, as I explain in the introduction to the book, at least three ways in which this field can be said to be ‘new’:

First, the law is new in a literal sense. The EU Foreign Subsidies Regulation and the UK Subsidy Control Act are novel pieces of legislation that share some features with the EU State aid regime but also depart from it in a number of respects. There is a dedicated chapter addressing each of these developments (and have been able to incorporate, inter alia, the new draft guidelines on foreign subsidies).

The law is also new in another sense. Following what I call the ‘permacrisis’ of EU State aid policy (where COVID was followed by the invasion of Ukraine, and this against a background of deglobalisation) a ‘new normal’ has emerged (epitomised by the Clean Industrial Deal Framework) that suggests that it may no longer be possible to turn back the clock to the pre-COVID era.

Finally, the tax rulings saga, the symbolic culminating point of which is the Court judgment in Apple (delivered exactly a year ago), ventured into issues that tested the boundaries of Article 107(1) TFEU and, more generally, the ability of the regime to address harmful tax competition. The saga has been so central to the development of EU State aid law that there is a whole chapter devoted to it.

I very much hope we will be able to celebrate the launch of the book, in London, Bruges and beyond, in the new year, and look forward to sharing those moments with many of you. Stay tuned in the meantime!

Announcing the 6th edition of the Rubén Perea Writing Award

Five years ago, our friend and colleague Rubén Perea Molleda passed away, just as he was about to embark on a promising career in competition law following his graduation from the College of Europe. Rubén’s memory remains vivid for everyone who knew him. To honour his memory, we established a competition-law and economics writing prize, which is already in its sixth edition.

As in previous years, the award-winning paper will be published in a special issue of the Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, together with a selection of the best submissions (the JECLAP special issue featuring the winner and finalists of the 5th edition will be out very soon; many articles are already available in Advanced Access). The winner may also receive the award from Executive Vice-President Teresa Ribera.

Who can participate?

In principle, you may only participate if you have not reached the age of 30 by the submission date (i.e., if you were born after 15 October 1995). Undergraduate and postgraduate students, as well as scholars, public officials and practitioners are all invited to participate. This award celebrates promising academic writing from individuals at the beginning of their careers. Our aim is to support and spotlight emerging voices. Thus, if your career path is non-traditional and you believe you align with the spirit of this award, we welcome a brief explanation for consideration here.

What papers can be submitted?

You may submit a single-author unpublished paper on competition law, policy, or economics, which is not under consideration elsewhere. The paper may be specifically prepared for the award, but it may be a redraft of an undergraduate or postgraduate dissertation. Please follow the following instructions: (1) the paper must not exceed 15,000 words (including footnotes, knowing that there is no need to include a no bibliography); (2) follow the JECLAP house-style rules, which can be found here; (3) please include a short summary in the form of 3-4 key points (single-sentence bullet points).

For your information, the Jury will assess your paper based on the following three main criteria: (1) clarity of writing; (2) depth of research; and (3) innovativeness. This year, the Jury will consist of Petra Nemeckova, Alfonso Lamadrid, Gianni De Stefano, Philip Marsden, Eugenia Brandimarte, Nicolas Fafchamps, David Perez de Lamo, and Lena Hornkohl.

How to submit?

Please submit the paper via this link: https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jeclap. IMPORTANT: As you go through the submission process, make sure that in Step 5, you answer YES to the question “Is this for a special issue?”, and indicate that your submission relates to the Rubén Perea Award.

What is the DEADLINE?

Papers have to be submitted by 23.59 (Brussels time) on 15 October 2025.

JECLAP Special Issue: Competition Law and Gender Perspectives

JECLAP is particularly proud to announce the publication of a Special Issue devoted to Competition Law and Gender Perspectives. The initiative owes a great deal to the indefatigable Lena Hornkohl, who has worked together with European Commission officials Johannes Holzwarth and Senta Marenz (both of whom are involved in DG Comp’s Equality Network).

The issue can be accessed here. It comes with an editorial by Lena, Johannes and Senta. As you can see from the list below, the pieces are invariably fascinating and cover a great deal of ground (with the added plus that many of them are available in Open Access). We very much hope this issue will contribute to raising the salience of gender issues in competition law.

Gender and Competition Law: An Exploration of Feminist Perspectives, by Giorgio Monti (Tilburg University)

Building a More Inclusive and Gender-proof Competition Law in Europe, by Baskaran Balasingham, Italo Leone and Linda Senden (Utrecht University)

Gender Inclusive Priority Setting in Competition Law Enforcement, by Kati Cseres (University of Amsterdam) and Or Brook (University of Leeds)

Influence of Gender Perspectives on the Work of Competition Authorities, by Lisa Leitner, Corinna Potocnik-Manzouri, and Nora Schindler (Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde Austria)

Diversity and Cartel Governance, by Johannes Blaschczok and Shazana Rohr (LMU Munich)

At first Blush—Taking a Competition Lens to Healthcare Pink Taxes, by Neha Georgie (Compass Lexecon Singapore)

Bridging the Innovation Gender Gap: Considerations under EU Merger Control, by Ece Ban (University of Oxford) and Carolina Banda (MPI for Innovation and Competition Munich)

Monopsony Power, Competition Law, and Women’s Informal Labour Markets in Latin America, by Germán Oscar Johannsen and Jeniffer Rodriguez (MPI for Innovation and Competition Munich)

Feminist Legal Education and Teaching Competition Law, by Mary Catherine Lucey (University College Dublin)

Can restorative remedies be imposed in EU antitrust law? Should they?

Remedies are now at the forefront of legal and policy discussions. As discussed here, this reality reflects a shift in the centre of gravity of enforcement (in the EU and beyond). The administrative priorities of authorities and the economic features of digital markets demand the administration of obligations that are regulatory in nature (such as the functional or structural unbundling of activities, access obligations and the determination of wholesale and retail prices).

A bare bones cease-and-desist order does the job in oligopolistic markets, but is often unable to deliver in industries (such as digital) that feature monopolies or quasi-monopolies across one or several levels of the value chain.

Authorities and commentators are catching up with this emerging landscape. For a long time, remedies were, at best, an afterthought (and not just in the literature). There is therefore every reason to welcome the structured conversation on the topic that is organically taking place.

The recent Report on the ex post evaluation of EU antitrust remedies, produced for the Commission, exemplifies the new trend. In addition, scholarship addressing remedy design and implementation is growing and taking fascinating new directions every time.

Is there room for restorative remedies in EU antitrust law?

Interestingly, the rise of remedies as a central theme in the EU antitrust arena has revealed that some basic issues are yet to be addressed systematically. Surprising as it may sound, something as fundamental as the very purpose of enforcement is not fully clear. For instance, many of the most recent contributions to the literature assume as self-evident that the point of remedies is (or can be) restorative in nature.

What authors mean by restorative is not always clear (there is a ‘thick’ and a ‘thin’ version of the concept, as I explain in the article cited above). The above said, the concept means, at a minimum, that remedial action should recreate the conditions of competition that existed prior to the infringement. Even in its more modest incarnation, therefore, restorative intervention would go beyond merely bringing the infringement to an end. It would require turning back the clock to where things were in terms of structure and competition dynamics.

If one reads carefully the EU case law, however, there is precious little support for the idea that restorative remedies can be imposed in EU antitrust law. One could take the argument further: the judgments that are typically relied upon to substantiate the claim suggest, if anything, that restorative intervention is, as the law stands, outside the reach of courts and authorities (at least so when they enforce Articles 101 and 102 TFEU).

This conclusion is particularly apparent from AKZO, which, paradoxically, is frequently mentioned in support of the proposition that remedial action can be restorative. As part of the remedy package in the case, the dominant firm was required to refrain from engaging in selective price-cutting.

The purpose of this measure was not to restore the conditions of competition that existed prior to the abuse. The Court (see para 155) is even explicit about the fact the remedy did not seek to re-allocate to ECS the customers it had lost to AKZO (which would have made it restorative in nature). The more modest ambition of the obligation was simply to bring the infringement to an effective end and prevent the abuse from taking place again.

Another common ruling that is mentioned in support of restorative intervention in EU antitrust law is Ufex, where the Court of Justice held that where the ‘anti-competitive effects continue after the practices which caused them have ceased’, the Commission ‘remains competent’ to ‘to act with a view to eliminating or neutralising’ them.

The best way to make sense of this passage is to take a look at the precedent to which it refers, namely Continental Can. This venerable classic of EU competition law concerned the abusive acquisition of a rival. In the specific circumstances of the case, the infringement could only be brought to an effective end by mandating a divestiture. The intervention was a mere adaptation of the nature of the infringement (a one-off) and its effects (which were not a one-off and thus lasted until intervention took place).

We are yet to see a judgment of the Court of Justice addressing the question of whether remedial intervention can go beyond merely bringing the infringement to an end. A good opportunity would have been Lithuanian Railways, as the one of the alternatives identified by the Commission in its decision was the restoration of the railway track. However, the remedy was not challenged by the dominant firm in its appeal (and, when contested before the General Court, the dominant firm did not claim that such a remedy exceeded the scope of the authority’s powers under Regulation 1/2003).

Should remedies be restorative in nature?

The fact that, as the law stands, there is little support for restorative intervention does not mean that such measures are necessarily beyond the reach of antitrust courts and authorities. Similarly, it does not rule out the possibility that the Court will accept them in the future. It simply means that one cannot take for granted that restorative remedies are feature of the system (or that a court or a competition authority are not acting decisively when they choose not to impose such measures).

It also means, more to the point, that it is necessary to have a conversation about their desirability. The arguments in favour of restorative remedies are well-known and definitely have force to them. In markets that change rapidly and that naturally tends towards concentration, merely bringing the infringement to an end may achieve little in some instances. If the role of antitrust law is to be taken seriously, the argument goes, it means that restorative intervention is a necessity, at least in some instances.

Arguments against this form of intervention are no less powerful. The single most persuasive one has to do, as usual, with the sheer complexity that comes with the design and implementation of restorative measures. We have witnessed in the past few years that getting remedies right in the digital arena is a complex task, even for the most sophisticated and well-resourced of authorities.

It is not clear that adding more demands to the already stretched antitrust institutions will be beneficial for the system. In this sense, I have always been of the view that creating the expectation that competition law can achieve more than it realistically is able to deliver is particularly harmful to its credibility (and its status in the EU legal order at large).

There is another factor to consider in this debate, which is equality of treatment. Would restorative remedies be imposed in some cases but not others? If so, on what basis? Could the matter be left to the discretion of the court or authority? One should not forget, in this sense, that the principle of equal treatment in the context of remedial action has featured prominently in the case law (most notably in the old ice cream cases, Langnese-Iglo and Schöller)

What matters, as I say, is to get the conversation started and discuss meaningfully the pros and cons of restorative intervention. Your comments, as ever, would be most welcome.

CALL FOR ABSTRACTS | JECLAP Special Issue on the DMA

The Digital Markets Act has been up and running for a while. We have witnessed, over the past year, the designation (and non-designation) of operators as gatekeepers, as well as the first judgments interpreting the Regulation. With this week’s non-compliance decisions against Apple and Meta, the regime may be entering a fascinating new era.

At JECLAP, we feel that the time is right to take stock of the evolution of the Digital Markets Act in the form of a Special Issue. It has been a lifetime since we last published on the regime (the Regulation itself had not even been adopted at the time).

JECLAP welcomes the submission of abstracts for consideration on the substantive, institutional and procedural aspects of the DMA, including (but not limited to) the following:

- The criteria for the designation of firms as gatekeepers.

- Emerging interpretation of the various substantive obligations (Articles 5 to 7).

- Judicial review of administrative action in the DMA.

- Procedural aspects.

- Interaction with competition law.

- Private enforcement of the DMA.

- Comparative perspectives.

If you have an idea for a paper, please email Gianni De Stefano (Gianni.De-Stefano@ec.europa.eu) or myself (P.Ibanez-Colomo@lse.ac.uk) by Friday 9 May with your proposal.

This proposal should take the form of an abstract of not more than 250 words in which you outline:

- The issue you would like to address;

- The angle you intend to take;

- The contribution your piece is expected to make; and

- Whether you have any actual or potential conflicts of interest (more information on what and when to disclose can be found here).

If your abstract is accepted (we will let you know as soon as possible), we expect the final article (ideally of around 7,000-10,000 words) to be submitted by mid-July at the latest.

As always, we will select abstracts to maximise diversity and balance in the Special Issue. We are, as ever, keen to give a voice to new authors and innovative approaches. If there was any doubt: we welcome legal and economic perspectives (and certainly papers that combine both).

In the meantime, do not hesitate to get in touch with any questions or suggestions!

Announcing the Winner and Finalists of Chillin’Competition’s 5th Rubén Perea Award

On 1 April 2020, almost 5 years ago, we lost Rubén Perea, a truly extraordinary young man who was about to start a career in competition law. We decided to set up an award to honour his memory, and to recognize the work of other promising competition lawyers/economists under 30. EVP Teresa Ribera has kindly agreed to deliver this award. As of this year, we also welcome EU Law Live as a partner in this initiative.

Today, we are announcing the winner and runners-ups of the 5th edition of this award. Thanks a million also to all those who submitted their work for this award. We received a large number of very good submissions and the Jury had a pretty tough time selecting the finalists.

And the winner of this year’s Rubén Perea Award is…

Pablo González Casín for his paper “Airline Cooperation and Competition Law: A Transatlantic Perspective. An analysis of Case Law and Unrealized Scenarios“.

The Jury also selected four other papers of particularly high quality. JECLAP will publish these papers in a special issue. These are:

- “From Economic Security to Legal Uncertainty: Exploring the Impact of the FDI Screening Regulation and Foreign Subsidies Regulation on Mergers and Acquisitions in the EU” (by Enrico Zonta)

- “Demand in Mobile Application Markets and the Role of Top Charts Ranking” (by Benedetta Gianola)

- “Optimal Fines in EU Competition Law – an Economic Analysis“ (by Adnan Tokić)

- “Smokescreens of Digital Markets – Choice Manipulation and the Illusion of Consent“ (by Naimy Paul)

Our warmest congratulations go to Pablo and to the four finalists.

This year’s jury included various experts, some of whom were also friends, former teachers or colleagues of Rubén, namely Petra Nemeckova, Gianni De Stefano, Lena Hornkohl, David Pérez de Lamo, Nicolas Fafchamps and Eugenia Brandimarte. Our gratitude goes to all of them for devoting part of their time to this project.

Opinion of AG Rantos in Case C‑2/24 P, Teva v Commission: consolidating and clarifying the object stage under Article 101(1) TFEU

Advocate General Rantos rendered his Opinion in Teva last week. The factual background is not new: it involves pay-for-delay arrangements, with which the Court of Justice has dealt regularly in recent years (including the Servier saga, discussed here and here). The action against the original Commission decision in Teva was dismissed by the General Court (see here). and the appellants – Teva and Cephalon – request that the first-instance judgment be set aside.

The case law on pay-for-delay has made important contributions to the assessment of the object of agreements under Article 101(1) TFEU. Above all, this steady stream of judgments has led to the adoption of a legal test that has been systematically applied since Generics. The test captures the substantive approach followed by the Court in the preceding the years.

As the Opinion of Advocate General Rantos shows, some questions keep coming back, even though – one might reasonably argue – they were already implicitly (if not explicitly) addressed in the previous case law. In this sense, the appeal provides the Court with an opportunity to clarify some issues at the margins.

The Court’s contextual approach to restrictions by object

The case law of the past decade makes it clear that the Court’s approach to the analysis of restrictions by object is contextual. Restrictions by object, in other words, are not abstract categories that can be mechanically applied to agreements. Whether or not a practice is, by its very nature, contrary to Article 101(1) TFEU must take into account the economic and legal context surrounding it. Only in such a way is it possible to establish whether the behaviour can be explained other than as a means to restrict competition.

The Court’s contextual approach is not an analysis of effects

In spite of the consistency of the Court’s position, it is not infrequent to read that the contextual approach to restrictions by object amounts, in essence, to evaluating the effects of the practice. According to this view, the current case law would conflate the object and effect stages of the analysis.

As explained elsewhere, there is a fundamental difference between ascertaining the object of an agreement in light of the relevant economic and legal context and assessing its effects on competition. The Teva case itself shows that the object stage is about making sense of the rationale behind the practice, that is, what explains the agreement between the parties. This assessment cannot be undertaken in the abstract. By necessity, it must consider the circumstances surrounding it. Doing so does not mean, however, that it must venture into effects territory.

An indispensable step of the analysis in pay-for-delay cases, which the Court explained at length in Servier, involves asking whether the parties to the agreement are actual or potential competitors (if there is no actual or potential competition to restrict in the first place, the agreement cannot be inherently anticompetitive). Semantic issues aside (see para 52 of the Opinion), this step does not entail an evaluation of the restrictive effects of agreements in light of the relevant counterfactual (as already clarified in Lundbeck).

The appellants in Teva, the Opinion suggests, sought to argue that the General Court engaged in an analysis of effects (thereby erring in law).

Advocate General Rantos relies on the existing body of law to explain that the General Court did not seek to ascertain the impact of the practice, but rather make sense of the ‘interests and incentives of the parties concerned, in order to ascertain whether the commercial transactions contained in the settlement agreement could have any explanation other than the commercial interest of the appellants not to engage in competition on the merits’ (para 56, emphasis in the original).

In other words, the General Court did nothing other than ascertain whether the Commission had correctly identified the object of the agreement in the relevant economic and legal context, as required by the case law.

The Court’s contextual approach does not entail a reversal of the burden of proof

Pursuant to the Court’s contextual approach, the authority or claimant have the burden of showing that the practice has no explanation other than a restrictive one. If there is no other plausible way to make sense of the behaviour, it will be deemed to restrict competition by object.

This test does not entail in any way a reversal of the burden of proof. It is not for the parties to the agreement to provide a plausible non-restrictive explanation for their conduct, but for the claimant or authority to show that such a plausible explanation does not exist.

While the above point seemed clear, one of the arguments in the appeal in Teva appears to be that the General Court’s assessment amounted to a reversal of the burden of proof. Advocate General Rantos explains (paras 59-64) why this argument does not reflect the reality of the case law (and, indeed, the analysis actually undertaken at first instance).

More than anything, the appellants’ argument is a valuable reminder that there is a difference between the legal burden of proof (what the authority or claimant needs to show to establish an infringement) and the evidential burden of proof (the evidence that the parties need to provide to challenge the arguments made by the authority or claimant).

It is uncontroversial to state that the parties to an agreement have the evidential burden of putting forward a plausible non-restrictive explanation for their conduct. It does not follow from this fact, however, that the legal burden of proof is reversed in any way.

In a similar vein, Advocate General Rantos rejected claims that the General Court had set a test that was impossible for the parties to meet. The parties need not show that an alternative explanation for the agreements is ‘certain’ (para 64). It is sufficient to show that it is plausible. The plausibility of the alternative explanation, however, cannot be merely pretextual (in the sense that it must be properly substantiated) and must be informed by the specificities of the case.

Case C-233/23, Android Auto (III): implications of the judgment

The first two instalments of the series focused, respectively, on the institutional and substantive contributions of the Court of Justice judgment in Android Auto. This third (and final) entry moves to the consequences of the ruling. There are three areas where the ruling may have a significant impact.

Product design and business models after Android Auto

As explained a while ago here, dominant firms’ choices in terms of product design and business models were, for decades (before Android Auto, that is), largely insulated from competition law scrutiny. This is true, for instance, of the degree of openness of an infrastructure. Absent evidence of indispensability, the decision by the operator about which features to open to third parties and which to keep for itself would be generally compatible with Article 102 TFEU.

Similarly, business models (that is, the strategies followed by firms to monetise the value they generate) was typically (if no presumptively) in line with EU competition law. As a rule, a dominant firm could keep for itself a feature of a partially open model as an aspect of its monetisation strategy. Again, this choice would have come under scrutiny only if the conditions set in Magill or Bronner had been shown to be met.

Following Android Auto, however, indispensability is no longer an obstacle to intervention where infrastructure operators (or input providers) decide to open their assets to third parties only partially. As soon as access is given in relation to one potential use of the input or infrastructure, indispensability ceases to be relevant across the board.

This shift in the case law is particularly consequential in the current economic and technological landscape. It expands authorities’ policy space significantly. One implication is that the design of products and the choice of business models may have to be reconsidered more often than in the past.

The analysis of effects becomes particularly relevant in the new legal landscape

The retreat of the indispensability condition strikes a new balance between short-term and long-term competition. It may well be the case that, in dynamic industries, indispensability sets too high a bar for intervention. This, in fact, was the point made by Advocate General Kokott and Mariya Serafimova in a recent piece addressing this very issue.

Whenever a new balance is struck, however, there is always a risk that the pendulum swings too far in the opposite direction. There is a risk, in other words, that the design of products and the choice of business models move from being (almost) presumptively lawful to being (almost) presumptively unlawful. A radical shift may not be the optimal one, whether from a substantive or an institutional standpoint.

In this new legal landscape, the analysis of effects emerges as a particularly relevant step in the assessment of potentially abusive conduct. The effects test will, in practice, act as the primary legal filter to strike the right balance between the static and dynamic dimensions of competition. It is not a surprise, against this background, that the Court stresses its importance in Android Auto.

In line with the preceding case law, the judgment emphasises that the analysis of the actual or potential impact of a practice cannot be a mere formality. As the Court put it, the assessment cannot be grounded in a ‘mere hypothesis’ (para 57). Instead, it must be based on ‘tangible evidence’ informed by the specificities of the case. Similarly, the ‘existence of doubt’ about the capability of a practice to produce actual or potential effects must ‘benefit the undertaking’.

Testing the meaning and limits of Android Auto

It seems likely, if not inevitable, that the meaning and limits of Android Auto will be explored in the coming years at the national and EU levels. With private enforcement on the rise (in particular in the context of Article 102 TFEU), national courts may be confronted with the sort of issues (imposing access obligations, determining the price of access, monitoring compliance) that only arose sparingly before them prior to the ruling.

This, it seems to me, is a third major consequence of the substantive innovations introduced in the judgment. There are many issues that are likely to be tested before national courts. One question relates to whether this judgment is confined to digital platforms. I do not believe it is (the key substantive innovation applies to all sectors, as I understand it), but I am aware that there is no consensus on this point.

A second obvious question relates to what ‘open to third-party undertakings’ actually means. The limits of this concept are not immediately apparent. If an operating system is open to third-party application providers but is not licensed to third-party device manufacturers, does Bronner apply where the latter seek access? Again, there is room for interpretation. For the same reason, this issue (and similar ones) may come back before the Court in the next few years.