Launch of The New EU Competition Law (POSTPONED)

We regret to inform you that we have been forced to postpone, due to illness, the even that we had scheduled for tomorrow to celebrate the launch of Pablo’s new book.

We will reschedule once Pablo is back on his feet, which we all trust will happen very soon!

The New Competition Law (II): whatever happened to the ‘more economics-based approach’?

I look forward to seeing many of you next Thursday in Brussels for the launch of The New EU Competition Law. The other half of Chillin’Competition, as well as other good friends of the blog, will be there. It promises to be fun.

The first post on the book addressed the institutional transformation that the EU competition law underwent with the adoption of Regulation 1/2003. Today’s entry focuses instead on the intellectual shifts that the discipline has experienced over the past 20 years, which I address in Chapter 2 of the book (‘The rise and decline of the “more economics-based approach”‘).

The ‘more economics-based approach’ was all the rage in the early 2000s. The modernisation of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU, which was the big buzzword at the time, referred both to the substantive and the institutional changes to the application of the two provisions.

In those days, it felt as if economic analysis was taking EU competition law to its own ‘end of history’. Articles 101 and 102 TFEU (in addition to merger control), it seemed, were changing for good. This is the context in which Christian Ahlborn and Jorge Padilla coined the term ‘Brussels consensus’ (see here for their original contribution) and captured the zeitgeist.

It does not feel this way anymore. If anything, the impression is that there a new consensus is forming around different ideas. Economic analysis is not absent from this emerging consensus: its role, however, is different.

What happened over the past decade? Why are the ideas driving the rise of the ‘more economics-based approach’ seemingly falling out of favour?

Chapter 2 explains that the key might lie with perceptions about what makes competition law enforcement legitimate.

The ‘more economics-based approach’ was, I argue, a rational response by the European Commission to a legitimacy crisis in the system. The authority understood that enforcement would not be accepted as legitimate if not informed by economic analysis.

Under the ‘Brussels consensus’ what matters, above all, is input and process. What matters, in other words, is that competition authorities rely on the best available expertise and that the assessment asks the right substantive questions. The outcome (that is, whether an infringement is established or not) is something about which the system is agnostic.

Things have changed over the past decade (I draw evidence in this sense, inter alia, from some of the leading conferences organised in Brussels).

With the rise of Big Tech, and under the influence of old and new ideas, what is expected from the competition law system is that it delivers. Enforcement is deemed legitimate, in other words, if it is able to enact change.

Many stakeholders are no longer satisfied with asking the right questions and pondering whether intervention is warranted in the specific circumstances of the case. The expectation is that authorities deliver the palpable, timely restructuring of digital and other markets.

Outcomes (as opposed to input and process) are now the driving force under the emerging consensus. A number of important consequences follow. One of them is that the relationship with economic analysis changes. Formal economics does not act as a constraint on enforcement (or not in the same way it did under the ‘Brussels consensus’).

A second one is that, if the existing tools do not deliver the desired outcomes (or do not do so in a timely and/or effective manner), then new tools are introduced. This is the background against which we must make sense of the adoption of the Digital Markets Act.

A third one is that the priorities change. A key tenet of the ‘Brussels consensus’ was scepticism vis-a-vis distributional issues, in particular in the context of Article 102 TFEU. The discipline would focus on exclusion, leaving the allocation of rents to other fields of law.

Not anymore: redistribution is front and centre of the new EU competition law, with all the fascinating substantive and institutional consequences that follow.

We will be discussing all the above, and much more, next week in Brussels. À bientôt, and all the best for 2024!

NEW PAPER | Competition on the merits

What is competition on the merits? This is the question I seek to answer in my most recent paper, available here.

The notion of competition on the merits seemed irrelevant not so long ago (that is, before Servizio Elettrico Nazionale exposed a friction in the case law). Landmarks of the 2010s such as Post Danmark I, TeliaSonera or Intel went about applying Article 102 TFEU without paying much attention (if any) to this notion.

Competition on the merits is now back in all discussions (and, for some, central to determine whether or not a given practice amounts to an abuse). Against this background, the paper seeks to answer two interrelated questions. What is competition on the merits? Does Article 102 TFEU apply to normal conduct or is an abuse an inherently ‘abnormal’ or ‘wrongful’ act?

It makes sense to start with the second. An overview of the case law suggests that normal conduct can be subject to Article 102 TFEU. ‘Normal’, in this context, means that the strategy is potentially pro-competitive (that is, firms can have recourse to it for non-exclusionary reasons) and that can be implemented by both dominant and non-dominant firms (that is, it is not the exclusive province of the former).

Exclusive dealing, tying and rebates (not to mention a refusal to deal with a third party) are all normal in this sense. However, we know well that they may amount to an abuse of a dominant position where certain conditions are met.

How about competition on the merits? The paper explains that this notion has become an irritant in the case law, in the sense that it is a source of confusion and frictions.

Tensions can be explained in part by the fact that the notion of competition on the merits was introduced at a time when the prevailing ideas about abusive conduct were very different from today’s.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was assumed that abusive practices could be identified ex ante and in the abstract. The underlying premise was that it was possible to draw a clear dividing line between unlawful conduct and legitimate expressions of competition on the merits.

The case law that followed (as well as the evolution of legal and economic thinking) moved away from these ideas. Whether or not most practices amount to an abuse is a context-specific exercise, not an abstract one detached from ‘all the circumstances’ surrounding their implementation.

If most practices are neither inherently good nor bad and the application of Article 102 TFEU is very much context-dependent, what is the contemporary role of competition on the merits?

My argument is that the notion of competition on the merits has role to play in the contemporary case law if it is interpreted in light of the ‘as efficient competitor’ principle (which has been a consistent feature in the judgments delivered over the past decade, including in yesterday’s ruling in Superleague).

Against this background, the argument provides a positive and a negative definition of the notion.

From a positive perspective, a dominant firm can be said to compete on the merits where it gets ahead in the marketplace with, inter alia, better, cheaper and/or more innovative goods or services.

The corollary to this positive definition is that, where the exclusion of a rival is attributable to the fact that the latter is less attractive along one or more parameters of competition, the practice is not abusive. Any exclusion would be the manifestation of competition on the merits.

From a negative perspective, a dominant firm does not compete on the merits in three instances.

First, where the practice has an anticompetitive object (that is, it makes no economic sense other than as a means to restrict competition). Pricing below average variable costs is the classic example in this regard.

Second, where the strategy involves the use of assets not developed on the merits (that is, assets that have been developed with State support, either in the form of State aid or the award of exclusive rights). In this instance, which was at stake in Post Danmark II, the ‘as efficient competitor’ principle would not be the benchmark against which the lawfulness of the practice is assessed.

Third, where the practice, while potentially pro-competitive, causes the exclusion of equally efficient rivals. In the latter, instance, the question of whether the behaviour is an expression of competition on the merits and that of whether it is exclusionary collapse into one and the same issue.

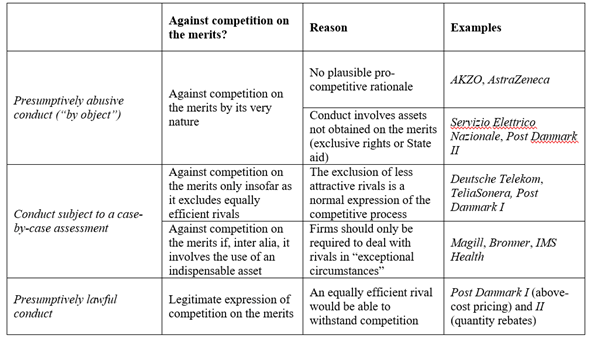

Based on the above, one can classify the case law in the manner you see on the Table below:

I would very much welcome your comments on the paper. As usual, I have nothing to disclose.

On Superleague and ISU: the expectation was justified (and EU competition law may be changing before our eyes)

Last year, in an editorial published in JECLAP, I asked whether Article 106 TFEU would change EU competition law. I pointed out that some rulings, including the General Court’s in ISU, gave the impression that Article 106 TFEU doctrines were slowly creeping into the case law dealing with Articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

The two (eagerly awaited) Court of Justice judgments in ISU itself and Superleague suggest that this transformation of EU competition law may well be under way, at least in relation to firms that have, de iure or de facto, the power to decide who gets to compete with them.

The key takeaway, in my view, is that organisations with such a regulatory or quasi-regulatory function are subject to the sort of obligations that apply to Member States pursuant to Article 106 TFEU. A distinct, stricter tier of competition law appears to govern the activities of such organisations.

Article 106-like obligations include, in particular, the respect of the principle of equality of opportunity and the duty to adopt rules that are transparent, objective, non-discriminatory and reviewable.

Any deviation from these obligations, when implemented by such organisations, presumptively amounts, it would seem, to a restriction of competition (and, more precisely, a by object infringement within the meaning of Article 101(1) TFEU and an abuse of a dominant position).

Article 102 TFEU in Superleague

The Superleague judgment starts with the application of Article 102 TFEU to FIFA’s and UEFA’s rules on the organisation of football competitions (and which may constrain third parties’ ability to run rival tournaments).

Some aspects of the ruling are strictly canonical, and capture the case law of the past decade (concerning, in particular, the ‘as efficient competitor’ principle). There are also interesting references to the notion of competition on the merits (on which I will follow up soon).

I find it particularly intriguing that the Court expressly refers to the object or effect of restricting competition in the context of Article 102 TFEU (see para 131 of Superleague: ‘conduct may be categorised as “abuse of a dominant position” […] where it has been proven to have the actual or potential effect – or even the object – of impeding potentially competing undertakings at an earlier stage‘; emphasis added).

In other respects, however, the judgment is genuinely innovative. As much as some recent General Court judgments, the Court relies upon the Article 106 TFEU case law applying to State measures, such as GB-Inno-BM, Merci convenzionali porto di Genova or MOTOE).

The overarching point seems clear: where an organisation is, de iure or de facto, in a position that is comparable to that of an undertaking enjoying exclusive rights, it is subject to strict non-discrimination obligations, aimed at preemptively addressing the risk of an abuse (para 138 of Superleague).

In the specific circumstances of the case, the Court strongly signals that rules on the prior approval of football competitions are not necessarily abusive. However, they must be subject to appropriate constraints if they are to be compatible with Article 102 TFEU.

Where an organisation has the regulatory means to decide go gets to compete with it, the judgment explains, there must be a substantive and procedural framework detailing how its regulatory powers are to be exercised (para 147 of Superleague). In the same vein, the organisation must avoid imposing sanctions in a discretionary manner (para 148 of Superleague).

Restrictions by object by sports organisations

The appeal in ISU focused on Article 101(1) TFEU, and more precisely on whether rules limiting (or prohibiting altogether) athletes’ ability to take part in some championships restrict competition by object. The Commission had taken issue with the so-called ‘eligibility rules’ laid down by the International Skating Union (and which went through various iterations over the years).

As I wrote a while ago, the General Court’s ruling introduced a novelty in its analysis of restrictions by object, in that it appeared to inject Article 106 TFEU case law (such as MOTOE) into the assessment. It also relied upon judgments like OTOC to substantiate its findings (even though the relevant passages from OTOC concerned the effects of the rules, as opposed their object).

The innovations introduced by the General Court have now been validated by the Court of Justice. Thus, the rules set by an organisation with a regulatory function must respect the principles of transparency, objectivity, non-discrimination and reviewability if they are to comply with Article 101(1) TFEU. Where they do not, they will amount to a restriction of competition by object.

Paras 131 to 149 of ISU depart in some respects from the canonical approach to the identification of restrictions by object (interestingly, and somewhat paradoxically, paras 101 to 108 of ISU are arguably the best and most elegant summary of the said canonical approach).

The analysis in ISU focuses more on the effects of the eligibility rules (and, more precisely, on the fact that they give the International Skating Union discretionary power and thus the ability to restrict competition and impose disproportionate sanctions) than on their object.

The ISU judgment appears to conflate, in other words, one and the other (and, similarly, borrow from the former to establish the latter). This cross-fertilisation had been carefully avoided in the past (establishing the object of an agreement in the relevant economic and legal context is indeed different analytically and conceptually from showing its effects).

However, it is not entirely impossible to rationalise the Court’s approach. When it comes to bodies with a regulatory function, the absence of checks is treated as a presumptive restriction of competition, without it being necessary to assess its impact. As already mentioned, a stricter tier of EU competition law appears to have been introduced.

The relationship between ancillary restraints and restrictions by object

There is another aspect of ISU that is worth emphasising. In para 113 of that ruling, the Court clarifies that the ancillary restraints doctrine applies only to agreement that do not have, as their object, the restriction of competition.

This point is, arguably, self-evident. The ancillary restraints doctrine presupposes that the overall agreement to which the clause relates is not restrictive by its very nature (if the agreement does not have an anticompetitive object, and the clause is objectively necessary to its operation, the latter escapes Article 101(1) TFEU altogether).

It is valuable and important, however, that the Court is explicit about this point. The issue may come back in future sports cases, and in particular the one dealing with agents’ regulation (which I discussed here). If the rules at stake in the case are found to be ancillary within the meaning of Meca Medina, it would mean, by implication, that their object is not anticompetitive.

REGISTRATION OPEN | The New EU Competition Law launches in Brussels (Fondation Universitaire) – 11th January, 5pm

The New EU Competition Law will launch in Brussels on 11th January (Fondation Universitaire, 5pm), with the support of LSE Law School and in cooperation with the College of Europe and its Global Competition Law Centre.

Click here to register for the event.

As you see in the programme below, I will be joined by a group of outstanding experts to discuss various aspects of the book. I very much look forward to seeing many of you there! Please get in touch in case you have any questions.

Programme:

17.00 | Welcome: Inge Govaere (Ghent and College of Europe)

17.15 | The New EU Competition Law : Mapping the Transformation

- Pablo in conversation with Pascale Déchamps (Autorité de la concurrence), Luc Gyselen (Arnold & Porter) and Marieke Scholz (European Commission)

18.15 | Break

18.30 | The New EU Competition Law : Looking into the Future

- Pablo in conversation with Filomena Chirico (European Commission and College of Europe), Alexandre de Streel (Namur and College of Europe) and Alfonso Lamadrid de Pablo (Garrigues and College of Europe)

19.30 | Closing remarks: Bernd Meyring (Linklaters and College of Europe)

19.45 | Drinks reception

The New Competition Law (I): the transformations of enforcement under Regulation 1/2003

The New EU Competition Law comes out this Thursday (check here for a 20% discount). As you see in the picture, I got to see the hard copies (finally!) last week, with that beautiful painting by Juan Gris adding life and colour to the cover (it is the second time his work features in a book of mine, and something tells me it will not be the last). And I started to get the urge to share with the world what the monograph is all about. Which takes me to the topic of this post.

The starting point of the book is the realisation that EU competition law has changed in fundamental ways since the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003. I felt that these mutations had not been examined systematically in a single monograph, but in disparate articles that addressed one aspect or the other. As is often the case, I found myself trying to put together something I could not find elsewhere.

What are the mutations that Regulation 1/2003 favoured? In essence, this regime gave more freedom to the European Commission: more freedom to decide which cases to investigate and more freedom to make the most of its limited resources.

The new institutional landscape led to two shifts (which I discuss in Chapter 1). First, the Commission has explored, significantly more frequently than in the past, into the substantive and institutional limits of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. ‘Market-shaping’ enforcement, in other words, has become a central feature of the contemporary landscape.

This transformation, alone, speaks to the success of Regulation 1/2003 and, more generally, of the EU model. It means that the Commission is not paralysed by fear (whether the fear relates to the exploration of new doctrines, the reinterpretation of existing ones or the implementation of the remedies) when applying Articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

Second, enforcement has become ‘policy-driven’, as opposed to ‘law-driven’. This phenomenon is not surprising. The Commission emphasised, in the lead up to Regulation 1/2003, that, after four decades, there was a ‘competition culture’ firmly in place in the EU and announced that, in the new landscape, it would make a more assertive use of its powers to advance its policy objectives.

The symbol of ‘policy-driven’ enforcement is the commitments decision, which has featured prominently in non-cartel investigations (in particular in ‘market-shaping’ cases, which demand, by their very nature, complex and resource-consuming remedies).

These two transformations have been compounded by a shift in the intellectual climate (addressed in Chapter 2) since the early to late 2010s. The modest, technocratic view of competition policy that dominated enforcement since the late 1990s progressively gave way to an approach that is less concerned with Type I errors and more with the effective application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

There appears to be a progressive move away from the ‘more economics-based approach’: a new consensus may well be developing around a different set of values.

These transformation of the institutional and intellectual landscapes have had several consequences for EU competition law (and, as I argue, have led to the emergence of a ‘new’ iteration of the discipline). My book focuses on two of these consequences.

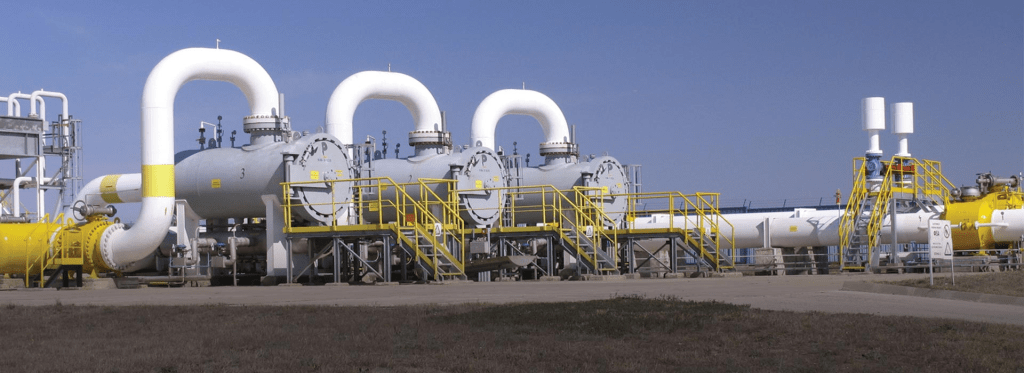

One of these consequences, which cuts across the whole of the book, is the permanent interaction with economic regulation (Chapter 3). ‘Market-shaping’ enforcement, by definition, is regulatory-like (it may lead, inter alia, to a duty to deal, to price regulation or to the redesign of products and business modelas).

Inevitably, it will enter into contact and interact with other regimes (such as telecommunications and energy regulation, which I cover extensively in Chapter 6). In some cases, Articles 101 and 102 TFEU have acted as a safety net or filled gaps in regulation; in others, they have gone as far as to rectify it or amend it de facto.

Occasionally, competition law has addressed a brewing ‘expectation of regulation’ that legislation may not be in a position to address fully and/or immediately (the legislative process is known to be often protracted and unpredictable).

Over time, it has become increasingly difficult (and increasingly pointless) to draw the line between competition law and regulation: it is no longer easy to figure out where one starts and where the other finishes. And it does not really matter. In a sense, the relationship between the DMA and Article 102 TFEU (and, indeed, the very existence of the DMA), encapsulates this idea well (as I argue in Chapter 5).

A second consequence is the change in the relationship with intangible property in general and intellectual property in particular (Chapters 4 and 7). During the formative years, EU competition law was largely deferential to intellectual property systems.

This attitude has changed over the past few years across a number of fronts that involve copyright and patents. I have discussed extensively many of these developments on the blog: taken together these developments signal a more assertive attitude vis-a-vis the malaise in intellectual property.

I very much look forward to discussing my ideas, on this platform and elsewhere. On this same note: remember that we will have a get-together on 11th January (Brussels) and 25th January (London). More details will follow soon!

SAVE THE DATES | The New EU Competition Law on tour: Brussels (11th January) and London (25th January)

The New EU Competition Law, my new monograph, is about to come out with Hart Publishing (the big day is just two weeks away). It is always exciting to write about one’s work of years, but sharing the news on Chillin’Competition is special.

After all, the project aims to capture, in a (hopefully) structured way, the many transformations that EU competition law has undergone and that we have discussed on Chillin’Competition. In a sense, it brings together what were once raw, disparate ideas sketched in individual posts.

The monograph discusses how the European Commission has enforced Articles 101 and 102 TFEU following the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003. This regime was designed to give the authority greater leeway to decide which cases on which to focus, freed from the shackles of the notification mechanism.

My main argument is that the current institutional architecture, together with the economic features of some industries, have led to the emergence of a ‘new’ competition law. From energy and telecommunications to patents and digital platforms, I trace aspects of this emerging approach to Articles 101 and 102 TFEU and discuss its transformative impact.

I will be summarising here some of the main ideas of the book in the coming weeks, including (i) the rise and decline of the ‘more economics-based approach’, (ii) the changing relationship between competition law and intangible property and (iii) how the DMA both encapsulates and trascends the ongoing phenomenon.

For the time being, please note that we will be celebrating the launch of the book in Brussels and London. It would be wonderful to see many of you there. Please save the following dates:

- Brussels (Fondation Universitaire): evening of 11th January.

- London (LSE Law School): evening of 25th January.

We will be following up with further details about the programme (rest assured it will not be just me talking about the book) and about how to register for both events (which they will be accessible for free).

If the above sounded interesting enough, take a look at his flyer, with more info about the project and with a discount code.

Developments on restrictions by object and ancillary restraints: EDP and FIFA Agent Regulations

For a long time, it was cliche to say that the notion of restriction of competition was and would always be shrouded in mystery. The numerous cases with which the Court of Justice and the Commission have dealt in the past decade make this cliche sound increasingly less accurate.

The law has reached the stage where it provides a structured set of principles that have greatly clarified the meaning and scope of Article 101(1) TFEU.

Two recent developments add to the existing body of knowledge, if only to confirm the consistent trends that we have been tracing in the blog over the years. Two weeks ago, the Court delivered its judgement in EDP. It is very much in line with the Opinion of AG Rantos already discussed in the past months (see here and here).

A second, more recent development relates to the regulation of football agents’ activities by FIFA, which has given rise to litigation at the national level (and a pending reference for a preliminary ruling before the Court of Justice; more precisely in Case C-209/23).

Politico informed here about the Commission’s position on the matter, which seems to support FIFA’s efforts to cap the fees that agents can obtain from transfer deals.

These two developments shed light on two important questions: first, they exemplify how the Court goes about identifying the object of agreements; second, they illustrate how the question of whether a clause is ancillary and that of whether it restricts competition by object are two separate stages that should not be conflated (but have been erroneously conflated, in particular in sports cases).

Identifying the object of agreements: price-fixing and market-exclusion

It has long been clear that the form of an agreement cannot determine, alone, whether it is restrictive of competition by object (for an extended discussion, see here).

The Commission’s submission in FIFA Agent Regulations provides a useful example of this point (the sort of example that captures the idea in a classroom context).

Formally speaking, FIFA’s rules deal with prices: they set a limit as to how much agents can make. One could be tempted to call them a price-fixing arrangement. This fact does not mean in any way, however, that these rules are caught by Article 101(1) TFEU (let alone by object).

What matters, as the Court has consistently held, is substance, not form. What matters, in other words, is the objective purpose of the fee cap, irrespective of how one calls it.

In line with the case law, the Commission appears to take the view that the cap on fees introduced by the FIFA can be rationalised on grounds other than a restriction of competition. According to Politico, the authority explained in its submission that these fees can address effectively the perverse incentives that agents may have to force a transfer (and thus pocket the corresponding fee).

From this (substantive) perspective, the object of the cap on fees would not be fundamentally different from the clauses at stake in, for instance, Cartes Bancaires: both rules would seek to ensure that a cooperative joint venture works adequately and that some undesirable incentives that could affect its functioning are tackled.

The Commission’s submission is remarkable for another reason: the vocabulary it uses. Politico quotes the authority as emphasising that the sports-related rationale advanced by FIFA is ‘plausible’. This reference to the plausibility of the explanation is drawn from Generics (para 89).

EDP provides another good illustration of these ideas. The Court holds that establishing whether an agreement (or clause) restricts competition by its very nature requires identifying is ‘precise object’ in the relevant economic and legal context (para 97).

Only following this assessment is it possible to come to a preliminary conclusion about whether the said agreement or clause is caught by Article 101(1) TFEU (for instance, because the object of the agreement is to restrict competition by dividing up markets or, as the Portuguese authority claimed in the case, by excluding a potential competitor).

EDP reminds us that there is an additional safeguard (para 103): the parties may always provide evidence that the agreement or clause is a source of pro-competitive effects. Where the pro-competitive effects raise a reasonable doubt about its nature, the ‘by object’ categorisation will be ruled out.

Ancillary restraints and ‘by object’ are two separate stages

In EDP, the Court deals with a point in an unceremonious manner, as if it were self-evident. However, this point is a frequent source of confusion. The judgement therefore makes a valuable contribution, in particular in light of the issues at stake in some pending cases.

The Court evaluated the compatibility of the market-exclusion clause in a fully orthodox way. It explained that the assessment of a restriction makes it is necessary to ascertain, first (paras 87-94), whether the clause is ancillary to the main agreement (which would mean that it escapes Article 101(1) TFEU altogether).

If it turns out that the clause is not ancillary, one needs to consider, second (paras 95-106), whether it has a restrictive object.

In other words: it is not because the clause fails to meet the criteria to qualify as an ancillary restraint that it is restrictive of competition. It would still be necessary to determine whether it is caught by Article 101(1) TFEU (be it by object or effect).

Some readers might think that the above is nothing more than a statement of the obvious and that, of course, ‘ancillary restraints’ and ‘by object’ are two separate stages of the analysis.

Other readers, however, may be reminded of recent developements, which show that ‘ancillarity’ and ‘by object’ are sometimes conflated. They have been conflated, in fact, in sports cases, including in the context of the FIFA Agents Regulation case.

In ISU, for instance, AG Rantos identified this error of law in the General Court judgment (see here for an analysis).

Two national courts (the Landgericht Dortmund and the Madrid Juzgado de lo Mercantil) appear to have incurred in this same error of law when evaluating the compatibility of FIFA’s cap on agents’ fees with Article 101(1) TFEU. The latter, for instance adopted interim measures only last week (see here).

If you read Spanish, you will see that the Juzgado de lo Mercantil claimed, in contradiction with the case law (and, it would appear, the Commission’s own analysis) that, if the FIFA rules are not ancillary, they could only be justified under Article 101(3) TFEU.

The Court will have the chance to address and clarify these matters soon, first in ISU and Superleague, then in the very FIFA Agents Regulation case. Electrifying times ahead.

Case T-136/19, Bulgarian Energy Holding (Part I: Substance)

Last Wednesday the General Court annulled the Commission’s abuse of dominance decision and €77 million fine in BEH (Judgment available here). The GC’s Judgment is a rare instance of a full annulment of a Commission abuse of dominance position (prior instances include the 2022 Qualcomm GC judgment, which the Commission did not appeal, the 1979 CJ Hugin judgment, the CJ 1973 Continental Can judgment and the CJ 1975 General Motors judgment).

But beyond anecdotal stuff and case-specific circumstances (a complaint filed by a company that was until 2021 jointly controlled by Gazprom against a public Bulgarian company performing public service obligations in a country dependent on Russian/Gazprom gas during a period in which Gazprom was abusing its dominant position), the reason why this case matters is because of its relevant contribution to the assessment of causality and evidence in abuse of dominance cases.

Remarkably, the GC found that BEH had an exclusionary “modus operandi” for a certain period (see paras 949, 1079, 1083 and 1089), but concluded that the Commission’s decision nevertheless failed in numerous critical respects. The judgment presents a very thorough fact and evidence intensive assessment by a first-instance court.

Here are a few preliminary observations on the substance of the Judgment (skipping the section on market definition and dominance, as well all the various pleas examined in great detail but ultimately rejected by the GC as unfounded or ineffective). Since this is a lengthy and fact-intensive Judgment (I’ve had more entertaining flight reads; at one point I kind of regretted having read the Judgment over the alternative I was carrying…), we will summarize and simplify the debate a bit. We will cover procedural issues in a separate post:

The conduct under examination. The conduct at issue was BEH’s (a vertically integrated state-owned energy company with a license to act as the sole public supplier of gas in Bulgaria) alleged attempt to block competing wholesalers’ access to key gas infrastructure in Bulgaria that it owned and operated (namely the gas transmission network, the only gas storage in Bulgaria, and the only import pipeline bringing gas into Bulgaria, which was fully booked by BEH). The Commission’s Decision found BEH dominant both in the gas infrastructure markets and in the gas supply markets in Bulgaria (a finding upheld by the GC), and concluded that it had engaged in a pattern of behavior aimed at preventing, restricting and delaying access to infrastructure.

Essential facilities doctrine – Bronner is alive (and so am I despite my recent, and not so recent, inactivity on this blog…) .The GC endorses the finding that the pipeline and the storage facilities at issue were essential facilities due to the lack of any alternative (as well as the finding that Bulgargaz was in a dominant position due to its control of the infrastructure even if it was not the owner of the facility). From para. 255 onwards (and in multiple recitals thereafter) the Judgment discusses the application of the Bronner conditions, highlighting the relevance of the indispensability conditions and the fact that the stricter Bronner test is justified because an obligation to conclude a contract “is especially detrimental to the freedom of contract and the right to property of the dominant undertaking” (para. 257, also 258, 282 and 451). The GC takes into account the fact that the facilities in question were built with public resources and the possible existence of a regulatory obligation to deal (e.g. paras 962 and 968-969). This is all fully in line with established case law.

A “refusal” to provide access and the issue of potential competition. One of the Commission’s allegations was that capacity hoarding on the essential pipeline constituted a refusal to supply. The GC finds that in order to prove that BEH’s conduct was liable to eliminate all competition in a neighbouring market on the part of the person requesting the service, there needs to be “proof that the potential competitor has, at the very least, a sufficiently advanced project to enter the market in question within such a period of time as would impose competitive pressure on the operators already present”, as otherwise the alleged effects would be purely hypothetical (para. 281, citing Generics and Lundbeck, also 447-452 which set a higher bar by requiring the Commission to establish rivals’ “firm determination”, “capacity”, “preparatory steps” and “sufficiently tangible project” to enter those markets). The GC concluded that in the case at issue these requirements were not met. In other (AG Kokott’s) words in Generics, there can be no restriction absent potential competition. In other (my) words, the question of whether a given conduct restricts competition needs to be established by reference to the degree of competition that would likely have existed in its absence because otherwise effects would be merely hypothetical. This, in my mind, is very sensible. The question of how far the Commission must go to establish what would have been a realistic/ likely counterfactual is a separate and case specific one.

Interestingly, the GC explains that, because of the serious interference on the freedom to contract derived from obligations to provide access, the dominant company must “be in a position to assess whether it is required to respond to it, failing which it might be exposed to the risk of an abusive refusal of access. However, a purely exploratory approach on the part of a third party to the dominant undertaking controlling access to the infrastructure in question cannot constitute a request for access, to which the dominant undertaking would be required to respond” (para. 282, also 450). The GC finds that the Decision did not show that BEH’s rivals had made a clear request for access to the pipeline to enter the Bulgarian gas supply market, that merely exploratory questions are not sufficient to show a sufficiently advanced intention to enter the market (para. 285, also 459 et seq.), and that requests made to another party (Transgaz) were not communicated to BEH (e.g. paras. 292-294 and 325-333).

Given its position in other cases and the upcoming Article 102 Guidelines, it will be interesting to see whether the Commission agrees with (or can live with) this idea that obligations to supply require an explicit request and an explicit refusal. For background, this is something that arguably does not feature in previous Commission decisions or in the case law, but that did feature in the GC Google Shopping Judgment (note that the President of Chamber and the reporting judge in that case are among the 5 judges signing this case too). I recently explained my view on this question before the Court of Justice, so I will avoid doing that here.

The GC also found that the Decision failed to show unreasonably stalling behaviour by BEH following a detailed analysis of the evidence and of the parties’ written communications which rather revealed a “constructive attitude” (e.g. paras. 359, 364, 395-396 and 442-443).

State action defense and protection of the dominant firm’s interests. Part of the Judgment (paras. 483- 687) is devoted to upholding the argument that some of the relevant conduct was imputable to Bulgaria and Romania negotiation of an agreement in a context characterized by Bulgaria’s dependence on Russian/Gazprom gas (which could only be transported through the controverted pipeline), which also explained BEH’s public service obligations aimed at ensuring security of gas supply in Bulgaria. This context appears to have weighted heavily on the GC, which underlines (i) that the State action defence makes it possible to exempt undertakings from their liability for conduct required by national legislation (paras. 548, 572, 616), and (ii) the legitimacy of dominant firms taking proportionate steps to protect their commercial interests (547, 616, 625). The GC finds that it was legitimate and reasonable for BEH’s subsidiary to take measures to guarantee a minimum capacity reflecting its needs as a public supplier. The GC did not make these findings under an “objective justification” analysis, nor did it examine “less restrictive alternatives”. Query whether the reasoning and outcome on this point would have been the same in a case involving a non-public company or in a situation where dependence on Russian gas were not relevant.

Causality/ Attributability. The assessment of causality /attributability of effects to the impugned conduct is one of the main issues at stake in pending Article 102 cases. It is also one of the topics that the Commission is expected to deal with in future Article 102 Guidelines. The case law requires that anticompetitive effects be attributable to the impugned conduct, and the Commission takes the view that “requiring a nexus of full causality between the conduct and the anticompetitive effects” would “render enforcement unduly burdensome or impossible” (EC Policy Brief, p. 4). In my view, this Judgment is mainly relevant because of its contribution to that debate.

As explained above, in this case the GC finds that an alleged refusal to deal cannot be likely to eliminate all effective competition in a downstream market where there is no evidence that the rivals requested access, or where there is no evidence that they had the firm intention to enter that market. This, in my mind, reflects a clear counterfactual thinking, an approach to causality not unlike the substantive reasoning in the Qualcomm judgment. As also explained above, the GC also found that part of the impugned conduct could be attributable to Member States or derived from BEH’s legitimate protection of its interests in light of its public service mission and obligations (see above).

In addition, and perhaps even more interestingly, the GC explains that even if BEH adopted an anticompetitive modus operandi that hindered rivals’ access to the transmission network and storage facilities and failed to comply with its regulatory obligations during a certain period (paras. 949-950, 953 and 1089-1100), this was incapable of restricting competition. This is because rivals lacked access to the only pipeline available to transport gas from Russia into those facilities “for reasons which are not attributable to proven abusive conduct” (para. 951; in my view, likely to be the most quoted paragraph of the Judgment in the future). In other words, the GC concludes that there is no restriction of competition (para. 953-954) because absent the impugned practices rivals would not have been able to compete anyway.

Another (Article 101) Commission decision in the same sector was already annulled on similar grounds (absence of potential competition) in EON/Ruhrgas. The peculiar regulatory framework applicable in these markets arguably makes things more complex for the Commission but, for that very reason, it contributes to triggering corrections and results in lessons that might be relevant across the board.

To be continued…

Sport and EU competition law (and much more) at this year’s mardis du droit de la concurrence

The legendary mardis du droit de la concurrence (the dean of all competition law events in Brussels, expertly run by Denis Waelbroeck and Jean-François Bellis) are back, like clockwork, this year. The programme started this week with an opening speech by Judge Savvas Papasavvas, Vice-President of the General Court.

You will be able to find more information on the programme for the remainder of the year (and on how to register) here. As you will see, it touches upon all the main areas of EU competition policy. The discussions will be led by top Commission officials:

- Tech-related issues (21st November, with Carlota Reyners Fontana);

- Abuse of dominance (5th December, with Max Kadar);

- Merger control (16th January, with Guillaume Loriot);

- Cartels (20th February, with Fernando Castillo de la Torre);

- State aid (16 April, with Ben Smulders).

The cherry on top will be a closing speech by Olivier Guersent.

I am delighted to be presenting, on 12th March, on EU Competition Law and Sports. As you may remember, I presented on this very topic at the mardis du droit two years ago, and the conversation that followed was so fruitful and inspiring that it led to an article (see here).

It will be a wonderful occasion to revisit some key debates and draw some lessons from ISU and Superleague. I very much look forward to seeing many of you there!