Case T-136/19, Bulgarian Energy Holding (Part I: Substance)

Last Wednesday the General Court annulled the Commission’s abuse of dominance decision and €77 million fine in BEH (Judgment available here). The GC’s Judgment is a rare instance of a full annulment of a Commission abuse of dominance position (prior instances include the 2022 Qualcomm GC judgment, which the Commission did not appeal, the 1979 CJ Hugin judgment, the CJ 1973 Continental Can judgment and the CJ 1975 General Motors judgment).

But beyond anecdotal stuff and case-specific circumstances (a complaint filed by a company that was until 2021 jointly controlled by Gazprom against a public Bulgarian company performing public service obligations in a country dependent on Russian/Gazprom gas during a period in which Gazprom was abusing its dominant position), the reason why this case matters is because of its relevant contribution to the assessment of causality and evidence in abuse of dominance cases.

Remarkably, the GC found that BEH had an exclusionary “modus operandi” for a certain period (see paras 949, 1079, 1083 and 1089), but concluded that the Commission’s decision nevertheless failed in numerous critical respects. The judgment presents a very thorough fact and evidence intensive assessment by a first-instance court.

Here are a few preliminary observations on the substance of the Judgment (skipping the section on market definition and dominance, as well all the various pleas examined in great detail but ultimately rejected by the GC as unfounded or ineffective). Since this is a lengthy and fact-intensive Judgment (I’ve had more entertaining flight reads; at one point I kind of regretted having read the Judgment over the alternative I was carrying…), we will summarize and simplify the debate a bit. We will cover procedural issues in a separate post:

The conduct under examination. The conduct at issue was BEH’s (a vertically integrated state-owned energy company with a license to act as the sole public supplier of gas in Bulgaria) alleged attempt to block competing wholesalers’ access to key gas infrastructure in Bulgaria that it owned and operated (namely the gas transmission network, the only gas storage in Bulgaria, and the only import pipeline bringing gas into Bulgaria, which was fully booked by BEH). The Commission’s Decision found BEH dominant both in the gas infrastructure markets and in the gas supply markets in Bulgaria (a finding upheld by the GC), and concluded that it had engaged in a pattern of behavior aimed at preventing, restricting and delaying access to infrastructure.

Essential facilities doctrine – Bronner is alive (and so am I despite my recent, and not so recent, inactivity on this blog…) .The GC endorses the finding that the pipeline and the storage facilities at issue were essential facilities due to the lack of any alternative (as well as the finding that Bulgargaz was in a dominant position due to its control of the infrastructure even if it was not the owner of the facility). From para. 255 onwards (and in multiple recitals thereafter) the Judgment discusses the application of the Bronner conditions, highlighting the relevance of the indispensability conditions and the fact that the stricter Bronner test is justified because an obligation to conclude a contract “is especially detrimental to the freedom of contract and the right to property of the dominant undertaking” (para. 257, also 258, 282 and 451). The GC takes into account the fact that the facilities in question were built with public resources and the possible existence of a regulatory obligation to deal (e.g. paras 962 and 968-969). This is all fully in line with established case law.

A “refusal” to provide access and the issue of potential competition. One of the Commission’s allegations was that capacity hoarding on the essential pipeline constituted a refusal to supply. The GC finds that in order to prove that BEH’s conduct was liable to eliminate all competition in a neighbouring market on the part of the person requesting the service, there needs to be “proof that the potential competitor has, at the very least, a sufficiently advanced project to enter the market in question within such a period of time as would impose competitive pressure on the operators already present”, as otherwise the alleged effects would be purely hypothetical (para. 281, citing Generics and Lundbeck, also 447-452 which set a higher bar by requiring the Commission to establish rivals’ “firm determination”, “capacity”, “preparatory steps” and “sufficiently tangible project” to enter those markets). The GC concluded that in the case at issue these requirements were not met. In other (AG Kokott’s) words in Generics, there can be no restriction absent potential competition. In other (my) words, the question of whether a given conduct restricts competition needs to be established by reference to the degree of competition that would likely have existed in its absence because otherwise effects would be merely hypothetical. This, in my mind, is very sensible. The question of how far the Commission must go to establish what would have been a realistic/ likely counterfactual is a separate and case specific one.

Interestingly, the GC explains that, because of the serious interference on the freedom to contract derived from obligations to provide access, the dominant company must “be in a position to assess whether it is required to respond to it, failing which it might be exposed to the risk of an abusive refusal of access. However, a purely exploratory approach on the part of a third party to the dominant undertaking controlling access to the infrastructure in question cannot constitute a request for access, to which the dominant undertaking would be required to respond” (para. 282, also 450). The GC finds that the Decision did not show that BEH’s rivals had made a clear request for access to the pipeline to enter the Bulgarian gas supply market, that merely exploratory questions are not sufficient to show a sufficiently advanced intention to enter the market (para. 285, also 459 et seq.), and that requests made to another party (Transgaz) were not communicated to BEH (e.g. paras. 292-294 and 325-333).

Given its position in other cases and the upcoming Article 102 Guidelines, it will be interesting to see whether the Commission agrees with (or can live with) this idea that obligations to supply require an explicit request and an explicit refusal. For background, this is something that arguably does not feature in previous Commission decisions or in the case law, but that did feature in the GC Google Shopping Judgment (note that the President of Chamber and the reporting judge in that case are among the 5 judges signing this case too). I recently explained my view on this question before the Court of Justice, so I will avoid doing that here.

The GC also found that the Decision failed to show unreasonably stalling behaviour by BEH following a detailed analysis of the evidence and of the parties’ written communications which rather revealed a “constructive attitude” (e.g. paras. 359, 364, 395-396 and 442-443).

State action defense and protection of the dominant firm’s interests. Part of the Judgment (paras. 483- 687) is devoted to upholding the argument that some of the relevant conduct was imputable to Bulgaria and Romania negotiation of an agreement in a context characterized by Bulgaria’s dependence on Russian/Gazprom gas (which could only be transported through the controverted pipeline), which also explained BEH’s public service obligations aimed at ensuring security of gas supply in Bulgaria. This context appears to have weighted heavily on the GC, which underlines (i) that the State action defence makes it possible to exempt undertakings from their liability for conduct required by national legislation (paras. 548, 572, 616), and (ii) the legitimacy of dominant firms taking proportionate steps to protect their commercial interests (547, 616, 625). The GC finds that it was legitimate and reasonable for BEH’s subsidiary to take measures to guarantee a minimum capacity reflecting its needs as a public supplier. The GC did not make these findings under an “objective justification” analysis, nor did it examine “less restrictive alternatives”. Query whether the reasoning and outcome on this point would have been the same in a case involving a non-public company or in a situation where dependence on Russian gas were not relevant.

Causality/ Attributability. The assessment of causality /attributability of effects to the impugned conduct is one of the main issues at stake in pending Article 102 cases. It is also one of the topics that the Commission is expected to deal with in future Article 102 Guidelines. The case law requires that anticompetitive effects be attributable to the impugned conduct, and the Commission takes the view that “requiring a nexus of full causality between the conduct and the anticompetitive effects” would “render enforcement unduly burdensome or impossible” (EC Policy Brief, p. 4). In my view, this Judgment is mainly relevant because of its contribution to that debate.

As explained above, in this case the GC finds that an alleged refusal to deal cannot be likely to eliminate all effective competition in a downstream market where there is no evidence that the rivals requested access, or where there is no evidence that they had the firm intention to enter that market. This, in my mind, reflects a clear counterfactual thinking, an approach to causality not unlike the substantive reasoning in the Qualcomm judgment. As also explained above, the GC also found that part of the impugned conduct could be attributable to Member States or derived from BEH’s legitimate protection of its interests in light of its public service mission and obligations (see above).

In addition, and perhaps even more interestingly, the GC explains that even if BEH adopted an anticompetitive modus operandi that hindered rivals’ access to the transmission network and storage facilities and failed to comply with its regulatory obligations during a certain period (paras. 949-950, 953 and 1089-1100), this was incapable of restricting competition. This is because rivals lacked access to the only pipeline available to transport gas from Russia into those facilities “for reasons which are not attributable to proven abusive conduct” (para. 951; in my view, likely to be the most quoted paragraph of the Judgment in the future). In other words, the GC concludes that there is no restriction of competition (para. 953-954) because absent the impugned practices rivals would not have been able to compete anyway.

Another (Article 101) Commission decision in the same sector was already annulled on similar grounds (absence of potential competition) in EON/Ruhrgas. The peculiar regulatory framework applicable in these markets arguably makes things more complex for the Commission but, for that very reason, it contributes to triggering corrections and results in lessons that might be relevant across the board.

To be continued…

Sport and EU competition law (and much more) at this year’s mardis du droit de la concurrence

The legendary mardis du droit de la concurrence (the dean of all competition law events in Brussels, expertly run by Denis Waelbroeck and Jean-François Bellis) are back, like clockwork, this year. The programme started this week with an opening speech by Judge Savvas Papasavvas, Vice-President of the General Court.

You will be able to find more information on the programme for the remainder of the year (and on how to register) here. As you will see, it touches upon all the main areas of EU competition policy. The discussions will be led by top Commission officials:

- Tech-related issues (21st November, with Carlota Reyners Fontana);

- Abuse of dominance (5th December, with Max Kadar);

- Merger control (16th January, with Guillaume Loriot);

- Cartels (20th February, with Fernando Castillo de la Torre);

- State aid (16 April, with Ben Smulders).

The cherry on top will be a closing speech by Olivier Guersent.

I am delighted to be presenting, on 12th March, on EU Competition Law and Sports. As you may remember, I presented on this very topic at the mardis du droit two years ago, and the conversation that followed was so fruitful and inspiring that it led to an article (see here).

It will be a wonderful occasion to revisit some key debates and draw some lessons from ISU and Superleague. I very much look forward to seeing many of you there!

The (second) modernisation of Article 102 TFEU: the acquis in the case law and the remaining uncertainties (II)

My paper on the (second) modernisation of Article 102 TFEU (see here) has been out on ssrn for around a week. I am really grateful to those who have already reached out with (their thoughtful and illuminating) comments, and would definitely welcome more.

A significant fraction of the paper is devoted to taking stock on the acquis on the notion of abuse and to identify the areas where some uncertainties remain. I thought the exercise made sense, given that the community is about to embark in a conversation about the codification of the case law.

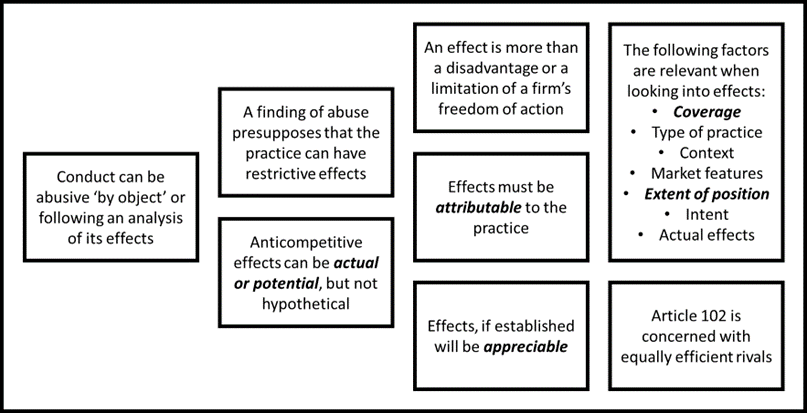

The acquis on the notion of abuse

The picture above, which you will also find in the paper, seeks to capture the contributions made in the long decade that has passed since the 2010 Deutsche Telekom. It easy to underestimate how much the case law has evolved during this period. One can now identify a number of principles guiding the interpretation of the notion of abuse, which are useful both in relation to old and new categories.

If I were to summarise the fundamental contributions made by the Court, I would emphasise the following developments.

First, it is now clear some practices are abusive only where they are a source of anticompetitive effects in the relevant economic and legal context. As a result, an authority or claimant will have to establish foreclosure to the requisite legal standard at least in some instances. This point may seem obvious now, but it was anything but straightforward in the aftermath of British Airways.

Second, anticompetitive effects must be attributable to the practice for Article 102 TFEU to apply. In other words, there must be a causal link between the practice and the actual or potential impact of the strategy.

The corollary of the second development is, third, that Article 102 TFEU is concerned, at least as a matter of principle, with equally efficient rivals. Where the exclusion of a rival is attributable to the fact that the said rival is less efficient and/or less attractive in terms of inter alia, prices, quality or innovation, Article 102 TFEU does not come into play.

The paper discusses two other key functions that the (much misunderstood) ‘as-efficient competitor’ principle has in the system.

This principle is also important from the perspective of legal certainty. As the Court emphasised in Deutsche Telekom, a dominant firm should have the means to assess whether or not its behaviour amounts to an abuse. For instance, one cannot expect a firm to adapt its conduct to the costs structure of a rival (which is the example given by both the GC and the ECJ in Deutsche Telekom).

More generally, the ‘as-efficient competitor’ principle is a valuable reminder that Article 102 TFEU is a device to protect the competitive process, not to engineer market outcomes and/or to decide how many and which firms should operate in the relevant market. The latter task is the natural province of sector-specific regulation, not of competition law.

Third, the Court has defined a number of factors that need to be considered when evaluating the actual or potential impact of a practice on competition. Post Damark II identified factors such as coverage and the extent of the dominant position. In addition, the features of the relevant market (including the regulatory context) played a central role in the assessment in that case (more in this below).

In Servizio Elettrico Nazionale the Court ruled, in line with the Guidance Paper, that evidence of actual effects (or the lack thereof) are to be considered (even if it is not conclusive in and of itself).

The remaining uncertainties

In spite of the abundant clarifications provided by the Court over the past (long) decade, there are, inevitably, some issues that need to be clarified (surprising as it may sound, the case law is still a work-in-progress).

One such issue is the probability threshold that applies when the analysis is prospective (that is, when the assessment concerns potential, as opposed to actual, effects). As I explain in the paper, this question is distinct from the definition of the standard of proof, even though both tend to be conflated very frequently.

The probability threshold is not just an academic diversion: it has major consequences for the definition of the scope of Article 102 TFEU. It is one thing to say that the threshold of potential effects is satisfied when the probability of harm is in the region of 10-15%, and another one to say that the likelihood of harm should be of at least 50% for Article 102 TFEU to apply.

As I discussed in the paper (and in previous pieces), the Court has not defined the probability threshold, but I agree with Advocate General Kokott, for whom the notion of potential effects presupposes a probability of harm of at least 50% (see her Opinion in Post Danmark II). It is the interpretation that best captures, in my view, what the Court has actually done.

A second issue that needs to be clarified relates to the assessment of the counterfactual. I have mentioned in the past that debates around this matter may seem surprising. Establishing a causal link between a practice and its effects demands, by definition, identifying a counterfactual. One could argue, therefore, that the Court has (if only implicitly) addressed this point.

What is more, the Court has already had the chance to clarify that the counterfactual is necessary in the context of Article 101 TFEU. I cannot think of a valid reason why the analytical framework would change depending on the applicable provision (it would amount to attaching different meanings to the same concepts based on whether one or the other is applied).

Third, it is not clear when and why departures from the ‘as-efficient competitor’ principle are deemed justified. In Post Danmark II, the Court ruled that the exclusion of a less efficient rival could be a concern insofar as the legal context made the emergence of an equally efficient one virtually impossible. In such a context, Article 102 TFEU protects the modicum of competition that sector-specific regulation allows. It remains to be seen whether, and why, other departures from the principle are possible

NEW PAPER | The (second) modernisation of Article 102 TFEU: reconciling effective enforcement, legal certainty and meaningful judicial review (I)

My new paper, devoted to the (second) modernisation of Article 102 TFEU is available on ssrn (see here).

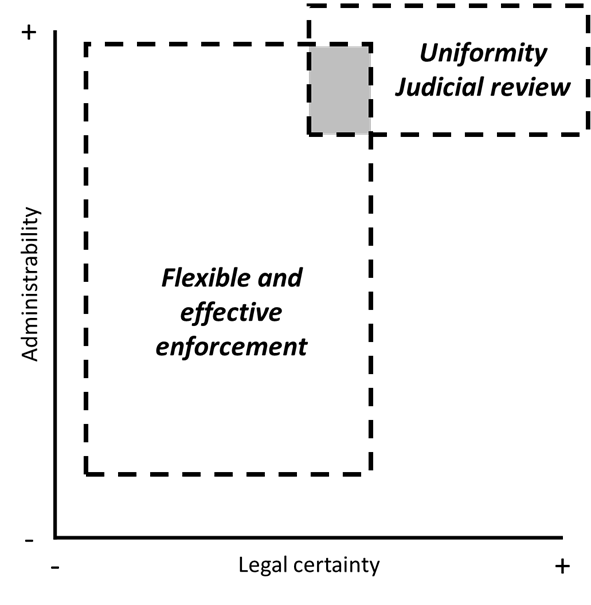

The point of the piece is, first, to provide the context behind the Commission’s ongoing initiative in relation to exclusionary abuses and, second, to discuss the way in which three central considerations (namely effective enforcement, meaningful judicial review and legal certainty) can be reconciled.

As the picture above and the figure below suggest, the exercise is not an easy one. It requires skilfully threading the needle to bring on board all three considerations.

The concern with effective and flexible enforcement (inescapable if Article 102 TFEU is to fulfil its role) must be addressed in a way that ensures that the law is uniformly applied across the Union and that judicial review remains meaningful (or, if one prefers, consistent with the allocation of powers in the EU legal order).

The paper suggests that the exercise, while challenging, can be assisted by a number of guiding principles and approaches.

First, the law must be administrable. If it were not, it would stand in the way of effective policy-making. It is submitted, in this regard, that administrability can be preserved by relying on ‘bright lines’ as proxies.

The AKZO case law already relies on a bright line (a 50% market share) as a proxy for dominance. It is submitted that several of the factors identified by the Court when defining the notion of abuse (coverage, nature and purpose of the practice, extent of the dominance) lend themselves naturally to this technique. For instance, effects could be deemed unlikely where coverage lies below 30%.

The use of bright lines would favour administrability (it would ease the burden of establishing an infringement), all while preserving legal certainty and allowing for effective judicial review.

It is submitted, second, that structured legal tests (a fixed, cumulative set of conditions with well-defined boundaries) are preferable to liquid or unstructured ones (that is, tests that rely on factors that may or may not be relevant in a given case and which therefore depend on a ‘holistic’ assessment).

It is explained, in this regard, that unstructured tests make it more difficult to ensure that EU law is uniformly applied across the Union. These tests are, by their very nature, a recipe for legal fragmentation (and particularly so in a decentralised legal order). They leave it, in effect, for national authorities and national courts to decide, case-by-case, the criteria against which the legality of practices is assessed.

For the same reason, liquid tests are not obvious to reconcile with full judicial review.

The paper argues, third, that substantive tests must be capable of being disproved. In other words, a set of conditions that are fulfilled always and everywhere is a bad legal test. It is submitted, in particular, that the interpretation of Article 102 TFEU cannot turn the analysis of effects into a mere formality.

The case law of the past decade suggests that this assessment is meaningful and context-specific. In the same vein, it cannot rely on a probatio diabolica or on a threshold of effects that would lead to a finding of foreclosure in virtually every instance.

Finally, there should be little doubt that the system must be allowed the necessary flexibility to evolve over time and adjust to new realities. An analysis of the case law suggests that there are ways to ensure that innovation remains compatible with the Court’s marked preference for continuity and consistency.

I will elaborate on some of these points in subsequent posts. In the meantime, I would really appreciate your thoughts on the paper (I am really grateful, by the way, to those who have alerady shared their comments). As usual, I have nothing to disclose.

Case T‑172/21,Valve v Commission: a (seemingly) straightforward case with some open questions of major significance

Background

Earlier this week the General Court delivered its ruling in Valve (see here). It addressed some of the legal issues that the Court of Justice did not, and could not, tackle in Canal+ (and which I discussed here). Because the latter case was decided by means of a commitments decision, the ECJ could not ‘definitively’ rule on whether the contentious clauses restrict competition by object (see para 54 of Canal+).

Valve, like Canal+, is about restrictions to the cross-border provision of copyright-protected content within the EU. Both differ from plain vanilla market integration cases in two ways. First, intellectual property is exploited in an intangible manner (as opposed to incorporated in, say, a Hello Kitty t-shirt).

Second, they are not subject to the exhaustion doctrine. As a result (and as the Court held in Coditel I), a copyright holder (or its licensee) may rely on its exclusive rights to preclude the cross-border provision of content.

These two differences can be consequential in individual cases. Because the copyright holder (or its exclusive licensee) can exercise its rights in relation to every communication to the public, cross-border trade may be prevented by the intellectual property system itself (that is, irrespective of whether there is an agreement in place).

In other words (and to use the vocabulary employed in Generics), the intellectual property system may, in some circumstances, represent an ‘insurmountable barrier to entry’ preventing the cross-border provision of services.

We know from the case law (think of Toshiba and E.On Ruhrgas) that, where the absence of (inter or intra-brand) competition is attributable to the regulatory context (as opposed to firms’ behaviour), the agreement under consideration does not restrict competition, whether by object or effect (this case law is elegantly summarised in Advocate General Kokott’s Opinion in Generics).

The (seemingly) straightforward

These precedents suggest that the key question to raise in Valve is whether there were ‘insurmountable barriers’ to the cross-border offer of video games via the Steam platform.

While the outcome of individual cases is never the focus of my analysis, I will note that, as far as I could gather from the public version of the decision (many crucial bits of which were confidential), Valve had received a worldwide non-exclusive licence to distribute the relevant video games via its platform (and therefore, it would appear, the right to distribute the said video games across the whole of the EU).

In such circumstances, it seems very likely (this is at least what the public version of the decision suggests) that any restrictions to cross-border trade would be attributable to the agreements, not to the copyright regime. For the same reason, the qualification of the said agreements as restrictive of competition by object seems in principle inescapable.

Assuming that the agreements (as opposed the copyright regime) are what preclude the cross-border provision of content, there would be no plausible rationale for the restraints other than the limitation of passive sales. This is, almost word for word, what the Commission argued in the case (para 211).

Summing up, the case seems, on the surface, straightforward. Some of the points made about the relationship between competition law and intellectual property, moreover, are wholly uncontroversial (such as the fact that the non-exhaustion of the rights does not preclude, as held in Coditel II, the application of Article 101(1) TFEU).

The open questions: a new relationship with intellectual property?

Other points, however, appear to go further than exisiting case law. They may perhaps be irrelevant in the context of the case, but they are definitely worth discussing. In para 203 of the judgment, the General Court suggests that a restriction of passive selling would be restrictive by object unless and until a national court declares that such passive selling amounts to a copyright infringement:

‘203. […] as is apparent from recitals 305 to 309 and 352 to 354 of the contested decision, the question whether or not […] passive sales by the publishers’ distributors could be the subject of legal proceedings before the competent national courts is not decisive for the purposes of the application of Article 101 TFEU […]’.

In other words, competition law, according to Valve, does not defer to the intellectual property system for as long as an infringement has not been expressly declared. In the same vein, the General Court appears to imply that licensees in different territories are presumed to be potential competitors before a copyright violation is formally established.

If the logic of the General Court were applied in an agreement like the one in Coditel II, the absolute territorial protection granted by virtue of the exclusive licence would be treated as a restriction by object pending a final declaration of an infringement.

It is difficult to overestimate the consequences of this interpretation of Article 101 TFEU. The presumptive validity of intellectual property titles (and, more precisely, the question of whether they raise ‘insurmountable barriers’ within the meaning of Generics) would bear no relevance in competition law analysis. These titles would only come into the picture once a breach has been proved.

The General Court’s arguments draw from the Commission decision in Valve. The latter, in turn, appears to be based on a reading of Generics that turns the specifics of the case into a general rule. Paras 49 and 50 in Generics deal with a very particular factual scenario, namely one where the primary patent had expired and where the relevant process patent did not and could not preclude potential competition.

The Generics case, in other words, was about an instance in which a presumptively valid intellectual property right was not an insurmountable barrier to entry.

The General Court judgment in Valve (just like the Commission decision) suggests the conclusions drawn in paras 49 and 50 of Generics are relevant in a different context, that is, one in which a presumptively valid intellectual property right would constitute such an insurmountable barrier. By doing so, Valve fundamentally changes, in passing, the relationship between competition law and intellectual property.

It remains to be seen whether this expansive interpretation of Generics will be embraced by the Court of Justice (either in Valve or a different case).

What can be said for the time being is that Valve is a manifestation of a wider trend in competition policy. The discipline is becoming less deferential, over time, to intellectual property. I have been tracing this evolution in forthcoming work of mine, which I look forward to sharing with the wider world. In the meantime, I would very much welcome your thoughts.

IEB Postgraduate Competition Law Course (27th edition) (in Madrid and online)

We are now opening up registrations for the 27th edition of the competition law program at the IEB in Madrid, which will run from January to March 2024. The course will follow a hybrid format (attendees can participate either in person or online). It is taught partly in English and partly in Spanish. Lectures take place in the afternoon (16h to 20h CET) to facilitate the participation of students joining from Latin America and the U.S.

We are proud to have, once again, an impressive panel of international lecturers, including Judges from EU and national courts, officials from the European Commission, the Spanish CNMC and other national competition authorities, as well as top-level academics, in-house lawyers and practitioners.

In addition to the possibility of registering for the full course, it is also possible to register for individual modules or seminars. The modules and seminars in this upcoming edition will be the following:

–Introductory session (12 January- afternoon).

–Module I – Agreements and Restrictive Practices: Vertical and Horizontal Agreements (15-17 January-afternoon). Coordinator: Carmen Cerdá Martínez-Pujalte (CNMC)

–Module II – Cartels and Procedures (22-24 January- afternoon). Coordinator: Isabel López Gálvez (CNMC)

–Seminar 1- Recent Developments in EU Competition Law (2 February- afternoon). Coordinators: Fernando Castillo de la Torre (Legal Service, European Commission) and Eric Gippini-Fournier (Hearing Officer, European Commission)

–Module III- Abuse of Dominance (5-7 February- afternoon). Coordinator: Konstantin Jörgens (Garrigues)

–Module IV – Merger Control (12-14 February- afternoon). Coordinator: Jerónimo Maillo (USP-CEU)

–Seminar 2 – Private Enforcement of the Competition Rules- New Challenges. (23 February- afternoon). Coordinator: Mercedes Pedraz (Magistrada, Audiencia Nacional)

–Module V- Sector Regulation and Competition (26 February-28 February). Coordinator: Pablo Ibáñez Colomo (LSE, College of Europe)

–Module VI – Public Competition Law: State Aid and Public undertakings (4-6 March- afternoon). Coordinators: José Luis Buendía (Legal Service, European Commission) and Jorge Piernas (Jean Monnet Chair, University of Murcia)

–Seminar 3 – The Digital Markets Act in Practice (15 March- afternoon). Coordinator: Alfonso Lamadrid (Garrigues, College of Europe).

We will also be holding three practical workshops dealing with inspections, distribution agreements and merger control.

Like every year, we are very grateful to the course’s sponsors, namely Araoz y Rueda, Clifford Chance, Compass Lexecon, Cuatrecasas, Garrigues, Gómez Acebo & Pombo, KPMG, Latham & Watkins, MLAB, NERA, Pérez-Llorca and Uría Menéndez.

For additional information, please contact competencia@ieb.es

The hidden gem in AG Rantos Opinion in Case C-331/21, AdC v EDP (and how it clarifies the case law)

Over the summer, I discussed Advocate General Rantos’ Opinion in in Case C‑331/21, AdC v EDP (see here for my post). I focused primarily on the notion of restriction by object. The case wonderfully illustrates why formalism fails when identifying ‘by object’ infringements.

While it may be tempting to claim that every market-sharing (or price-fixing) agreement between competitors is caught by Article 101(1) TFEU by its very nature, the case law abundantly shows (most recently in Super Bock) that it is not true. AdC v EDP will add to this body of case law when it comes out.

The Opinion hides a valuable gem that is equally crucial to make sense of the case law, that clarifies some perceived inconsistencies and that, as far as I have been able to see, has not been discussed elsewhere. It is a tricky point that lends itself to confusion and deserves to be addressed in some detail.

Advocate General Rantos is a case study on how restrictions by object are identified in theory and practice. It elaborates on every single key aspect. The anaytical sequence can be summarised around the following points:

- First, the clause is typically the relevant unit of analysis of restrictions by object.

- Second, whether or not the clause in question is restrictive by object is considered in light of the relevant economic and legal context, which certainly includes (if there was any doubt) the analysis of the agreement.

- Third (and this is where the Opinion kicks in), once the contextual analysis reveals that the clause is restrictive by object, it is no longer relevant that other clauses within the agreement are not (following the second step, in other words, there is no second bite of the cherry).

This clarification was particularly relevant in the context of the case. The question raised by the national court concerned specifically a market-sharing clause. We know that even restraints that, at first glance, come across as problematic (including price-fixing and market-sharing itself), are not necessarily restrictive by object.

As already discussed at length in the preceding post, the case law and administrative practice provide many examples showing that the agreement is a key aspect of the evaluation of the relevant economic and legal context. It often sheds light on the object of individual clauses. It may show that such clauses are not anticompetitive and/or that they do not restrict competition at all.

As explained by the Commission in its 2014 Guidance on restrictions by object, a price-fixing clause in an agreement between competitors may not be a ‘by object’ infringement when it is introduced in the context of a (pro-competitive) joint production agreement. In Erauw-Jacquery the contextual analysis led the Court to conclude that the export prohibition in the case (in principle a no-no) was not caught by Article 101(1) TFEU because of the role it fulfilled in the overall agreement.

Sometimes, the analysis of the clause in light of the agreement reveals that it is ancillary to the latter. In Pronuptia, for instance, the Court distinguished between the restraints that were integral to the operation of the franchising agreement (and thus fell outside the scope of Article 101(1) TFEU altogether) and those that were not (such as territorial exclusivity).

However (and this is where Advocate General Rantos’ contribution is particularly valuable), once the analysis of the clause in its economic and legal context reveals that its object is anticompetitive, it does not matter whether other clauses in the agreement are not restrictive by their very nature.

In other words: the agreement informs the contextual assessment of the object of the clause. Once the object is figured out (and it turns out that it is restrictive by its very nature), whether or not other clauses are pro-competitive is no longer relevant.

To some extent, this point is obvious. The parties to an agreement can try and disguise a cartel arrangement in an agreement that has a broader scope and set of aims. The fact that the rest of the agreement would be beyond reproach would not allow them to escape the prohibition (and the fines that come with it).

In other respects, however, it is a point that is worth making. For the sake of simplification, we often refer to the agreement, not the clauses (for very good reasons).

More to the point, Advocate General Rantos’ analysis is helpful because it helps us make sense of what might seem a tension in the case law but that, upon closer inspection, is not.

Thanks to the judgments delivered over the past five years, the picture on restrictions by object is as clear as it has ever been. Landmarks such as Generics and Budapest Bank make it clear that, where a restraint is a plausible source of pro-competitive gains, it is not restrictive by object (see here for an analytical framework I prepared when the second of these judgments came out).

Reasonably, someone may be tempted to reply to the above by asking: has the Court not held, in ANSEAU-NAVEWA and BIDS, that an agreement (or clause) may restrict competitio by object even if it has other, pro-competitive aims? Would this fact not show that the above interpretation is incorrect?

Advocate General Rantos gives us part of the answer to that question and shows that there is no tension between the two lines of case law.

It may well be that an agreement, taken as a whole, has other pro-competitive aims. As explained in the Opinion, however, this point is irrelevant once it has been established that a particular clause is restrictive by object (that is, once it is shown that it has no plausible objective purpose other than an anticompetitive one in light of the relevant economic and legal context).

New JECLAP Issue: In Memoriam Valentine Korah

Issue 5 of this year’s volume of the Journal of European Competition Law & Practice came out a few days ago. It is dedicated to the memory of Professor Valentine Korah.

We pay tribute to her life and achievements in an editorial, which is available for free here. As we point out, every issue of JECLAP (with its blend of academic scholarship and practical application of the law to specific problems) is in a way a celebration of Professor Korah’s approach to EU competition law.

NEW PAPER | Form and substance in EU competition law

As one would expect from a proper rentree, I have just uploaded on ssrn (see here) a new paper, entitled ‘Form and substance in EU competition law’.

The piece deals with the unlikely comeback of formalism in competition law discussions. Formalism may be back, but the tone and substance of the debates are different from those of yore. During the 1980s and 1990s, formalism was criticised by those that championed the ‘effects-based approach’ and favoured restraint in the enforcement of competition law provisions.

In the past couple of years, formalism has been questioned for the opposite reason. Some leading commentators and practitioners see formalism as an obstacle to effective policy-making. From this perspective, the use of structured legal tests (such as the three Magill conditions or the ‘five criteria’ introduced by the Court in Intel) would hinder authorities’ ability to deal with anticompetitive conduct.

Against this background, the paper seeks to clarify what we mean by formalism (or form-based approach). It seems to me that people refer to different realities when they use the term.

The term was originally used to refer to an approach whereby the (i) categorisation and (ii) lawfulness of practices depend on their form (and their form alone). The meaning changed over time. For some, the ‘by object’ treatment of conduct is synonymous with formalism. For others, the use of structured legal tests (as opposed to unstructured or ‘liquid’ approaches), is also a manifestation of the phenomenon.

One of the conclusions of the paper is that it would be incorrect to conflate ‘by object’ and formalism. The analysis of the restrictive nature of an agreement is not necessarily formalistic. It can also rely on a substance-based approach. In the same vein, the paper explains that the use of legal categories is not inherently (and not always) formalistic. As pointed out by Wouter Wils in his instant classic on Intel, categories are a necessity in any legal order.

Another conclusion is that the Court of Justice has consistently placed substance above form both when it comes to assessing the object of agreements and when defining legal categories. There are two salient (and relatively recent) examples in this regard.

Super Bock confirmed that the form of an agreement does not and cannot determine, alone, whether it is restrictive of competition by object. The so-called ‘object box’ is elegant, intuitively appealing and incredibly useful as a first approximation to the issue, but does not reflect how the Court really goes about it.

After Super Bock (which implicitly overrules Binon), the last remaining pocket of formalism has fallen: resale price maintenance can no longer be said to amount, in the abstract, to a ‘by object’ infringement. The need to consider the ‘economic and legal context’ knows no exceptions.

Slovak Telekom, in turn, illustrates the substance-based approach that the Court follows vis-a-vis the definition of legal categories. According to the judgment, the applicablity of the Bronner test does not depend on formal criteria, but on substantive factors, namely whether requiring a dominant firm to deal with third parties would interfere with its right to property and its freedom of contract.

It would be really wonderful to get your thoughts on the paper. Do not hesitate to contact me. And, as ever, I am delighted to clarify that I have nothing to disclose.

Valentine Korah (1928-2023)

Valentine Korah left us a few days ago. It has been very moving to hear and read the tributes of those who worked with and were close to her. When I entered the competition law world, Professor Korah was no longer as active as she used to. However, her mark and contributions to the discipline were impossible to miss. She had greatly contributed to shaping the law and institutions I was discovering in the mid-2000s.

Professor Korah’s work on, inter alia, vertical restraints and technology transfer agreements was so foundational that there was simply no way around it. To this day, I still find interesting stuff in her articles. It is not unusual that I realise that something that I believed was a novel insight was already there, black on white, eloquently put.

If there is something I would highlight about Professor Korah’s legacy, is that how passionate she was about research in general and competition law in particular. The first memory that comes to mind is that of her sitting in the first row of a seminar room at UCL, well into her 80s, willing to learn from younger scholars, and keen to improve their work. May she rest in peace.