Archive for March 2010

Lateral Hires

A very short post to congrat our friend Andrés Font Galarza for his nice move to Gibson Dunn & Crutcher LLP.

TV Appearance

The European Parliament’s (EP) resolution on competition policy adopted a week ago has gone largely unnoticed (it is an answer to the Commission’s Annual Report for 2008). Shortly after the Lisbon Treaty, of which the EP is the big winner (source, P. CRAIG), this resolution signals the EP’s intention to be more vocal on antitrust issues. The resolution contains a great number of proposals, such as a: (i) call for introducing individual sanctions for competition law infringements; (ii) a greater focus on small and medium enterprises; and (iii) requests for the opening of sector inquiries. My gut feeling: I am skeptical as to what the Commission should do with this. This resolution may further politicize competition matters, and I therefore dislike it.

The good thing though: I was interviewed on Canal Z channel. The link to the interview can be found here (around 2.10).

Thanks to E. Provost for the pointer.

Guidelines

The upcoming guidelines on horizontal cooperation agreements will fill long lasting gaps. They will include some wording on standardization and information exchange agreements. I paste hereafter the words of the new DG COMP Director General in his first speech (three days ago):

The review of the horizontal guidelines is a good opportunity to clarify what is expected from standard setting organisations as regards disclosure obligations on both pending and granted patents if their standardisation agreements are to comply with the provisions of Article 101. It is also a good opportunity to include some guidance on the meaning of what are fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (“FRAND”) terms for companies licensing technology. One possibility would be to include a mention of the benchmarks that could be used to assess whether the licensing terms are actually fair and reasonable.

On information exchange, the new guidelines are a good opportunity to provide legal and economic guidance to companies. Our intention is for the guidelines to specify what is considered to be a clear-cut restriction of competition or for example what are the market characteristics that may lead to an exchange of information having a collusive outcome. The guidelines should also give guidance on economic efficiencies that can be created by an exchange of information such as solving problems of asymmetric information or seeking a more efficient way of meeting of demand. It is also the intention that the guidelines will contain many examples as illustration, which will help companies in their assessment. Here again, more legal certainty will be conducive to a better competitive environment.

Misc.

I’ll keep it short for today.

A reminder: next week the GCLC will have its next lunch talk on the Commission’s proposed best practices in antitrust proceedings.

An info: the slides of the IEJE conference on the Lisbon Treaty are available here.

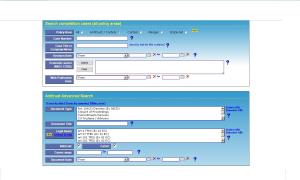

Search engine

This is not a post about Google.

I had not noticed this earlier, but DG COMP has a new search engine for antitrust, merger and State aid cases. It looks very user friendly and will be undeniably of great help to most competition law practitioners and academics. A welcome initiative.

Outcome discrimination

A Microsoft-related post to compensate for the disappearance of the post uploaded earlier.

Recital 13 of Regulation 1/2003 provides that:

“Commitment decisions are not appropriate in cases where the Commission intends to impose a fine“. The ratio of this rule has to do with the fact that commitments only have corrective effects for the future. Unlike fines, they fail entirely to punish past anticompetitive conduct – behavior that has actually caused harmful effects – and are thus inappropriate in case of lasting competition law infringement.

Think of Microsoft II where the Commission accepted commitments. Take a breath. Now think of Microsoft I: same type of alleged anticompetitive conduct, same company, but in this case a staggering 497 million € fine (for two infringements though). My question: can in such situations the Commission’s discretion over the outcome of a case be challenged on grounds of unlawful discrimination? Although I doubt it, I find the point quite interesting (I allude to it in my last concurrences paper).

Windows

This is not a post on Microsoft.

In a move to make their films available early through various channels (DVD, VoD, etc.), movie distributors – big fishes like Disney – have sought to reduce the x-months exclusivity enjoyed by theatres over the first release of movies (the so called theatrical “window”).

Historically, movie distributors had been reluctant to do this, because the release of movies on a wide number of physical (DVDs) or digital (Internet) formats rang the opening hour of piracy. Moreover, the theatres’ temporal monopoly over the distribution of movies led to fat prices for consumers, and thus appreciable margins for the movie distributors (which normally receive a % on each ticket sold).

Movie distributors are manifestly changing their minds. A plausible explanation of this is that distributors increasingly perceive the theatrical window’s lenghty exclusivity as a key explanation for movie piracy. In addition, in times of crisis, consumers may prefer to stay home to watch movies, so the revenue generated by theatrical distribution decreases as compared to other formats. Think, for a second, to the situation of a budget-constrained family man. To him, watching a movie home is akin to a fixed cost. It is incurred once (renting the DVD) and can be spread over the various members of the family. By constrast, watching a movie in a cinema is a variable cost, which increases with the number of family members brought to the theatre.

So much for the theory. Why a post on this issue? On the occasion of the release of “Alice in Wonderland“, cinema chains have tried to undermine the distributors’ attempts to shrink the theatrical exclusivity window. To this end, they have engaged into the most brazen form of anticompetitive conduct: boycott. In the UK, it has for instance been reported that the three big cinema chains – Odeon, Vue and Cineworld – initially threatened to boycott Alice in Wonderland. The same has also happened, and may still be happening, in a number of European countries (Belgium, the Netherlands).

Under EU competition law standards, such boycott practices may be challenged on two possible grounds. First, they constitute a refusal to purchase movie distributors’ services (or they entail the termination of long lasting commercial relationships) and may thus be tantamount to an unlawful abuse pursuant to Article 102 TFEU (or its national equivalent). Assuming – I sound like an economist – that the theatres hold a dominant position (individual or collective), the interesting issue lies in the fact that theatres do not try to harm competition on a secondary upstream market as in classical “essential facility” cases (where upstream, or downstream, foreclosure is the concern). As a result, the Magill/IMS/Microsoft case-law which requires the elimination of competition on a secondary market should thus not apply to cinema chains practices. Yet, I am tempted to argue that there could nonetheless an abuse pursuant to Article 102 TFUE. In coercing distributors to maintain the current release windows through boycott, theatres artificially forestall the early entry of alternative viewing modes on the market. This in turn is prejudicial to “consumer welfare” in the meaning of competition law since it limits consumer choice and impedes the development of new markets. The increased emphasis of “consumer welfare” under Article 102 TFUE brings support to this interpretation.

Second, such practices may be tantamount to an infringement of Article 101 TFUE (or the national equivalent), provided the cinema chains have jointly decided to boycott movie distributors – again I sound like an economist. EU competition law has a strong enforcement record against collective boycotts. Back in 1974, the Commission held in Papiers peints de Belgique that “collective boycott is amongst the most egregious violations of competition rules”.

Apologies for the long post, but I find the issue fascinating. Thanks to T. Hennen for the pointer.

(Image possibly subject to copyrights: source here)

43rd Lunch Talk of the GCLC – 18 March

The 43rd Lunch Talk of the GCLC will be devoted to The Commission’s Proposed Best Practices in Antitrust Proceedings. We are delighted to have Luiz Ortiz Blanco (Garrigues) and Carles Esteva Mosso (DG COMP), to discuss the Commission’s text. The lunch talk will take place on 18 March at the Hilton Hotel in Brussels (38 Boulevard de Waterloo).

See hereafter for registration form.

Competition Law and Sport (II) – Football: State aids and salary caps

Last Wednesday UEFA published an interesting report which provides thorough and useful information about the financial status of European football clubs. A quick look at the report reveals at least a couple of issues that bear a strong relationship with competition law:

Firstly, UEFA’s report advocates the need for “financial fair play” (in essence: more transparency and financial responsibility) in order to address a problem highlighted in Platini’s foreword: “[t]he many clubs across Europe that continue to operate on a sustainable basis (…) are finding it increasingly hard to coexist and compete with clubs that incur costs and transfer fees beyond their means and report losses year-after-year”.

According to the report, most European football clubs face recurrent losses. The most important leagues, both on the sporting level and economically wise, are the ones with the greater aggregated debt: Premier League Clubs have a net debt of approximately 4000 million euros, followed by Spanish First Division Clubs with a debt of nearly 1000 million.

The inevitable question is: how do clubs operate in spite of such losses? In many instances shareholder’s contributions do the job, but in many other situations clubs subsist thanks to public intervention, which in some cases could qualify as State aid. In the sports sector, as in any other, State aid can appear under multiple guises (e.g. direct subsidization; sponsorship under non-market conditions; non-collection of tax or social security debts; aid for the construction of sports infrastructure; etc). One would expect the European Commission to intervene increasingly more in this sector or, alternatively, to lay down specific rules for the assessment of State aid in the world of sports.

Secondly, the report insists on the fact that the financial perspectives of European clubs presage an even worse future. The report seems to blame the constant increase in player’s salaries, which amount to more than 60% of clubs’ expenses, a proportion that is steadily rising. It is on the basis of this and similar data that UEFA has for some time been proposing to establish a salary cap in European football. The compatibility of a salary cap with EU competition law is unclear. In fact, it was listed as one of the “main pending and undecided issues” in Annex I to the White Paper on Sport: sport and EU competition rules.

All the above seems to confirm something I mentioned on a previous post: the world of sports will be an important and growing source of interesting and complex competition-related issues in the very near future.