Counterfactual analysis and restrictions by object: myths and misconceptions

Alfonso’s post on the counterfactual (the best we have published so far this year) made me think of a crucial question that, I believe, it is still very much misunderstood. Often, I hear people say that the counterfactual analysis ‘does not apply’ to restrictions by object, or that it is not relevant in that context. The question is important, as it is crucial to make sense of some major pending issues. I am in fact looking forward to presenting a paper on the counterfactual at the Oxford Antitrust Symposium later this year.

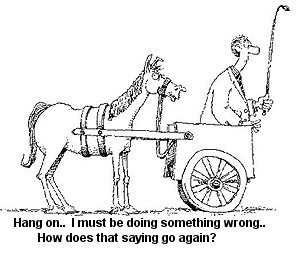

This (relatively widespread) view is, I believe, based on a fundamental misunderstanding about the notion of restriction by object, and about how to go about it in practice. Those who support this view seem to argue, in essence, that the conclusion of the analysis (ie the legal qualification of the agreement under Article 101(1) TFEU) comes before the analysis itself, and not vice versa. To put it graphically (and this is what explains the picture you see above), it is a bit like putting the cart before the horse.

More importantly, this view is contradicted by the case law of the Court of Justice, which makes it abundantly clear that the counterfactual should be considered irrespective of whether the analysis would lead to the conclusion that the agreement is restrictive by object or effect. In other words, what leads to the conclusion that the agreement is restrictive of competition is the evaluation of the counterfactual, and not the other way around.

Some examples

It makes sense to illustrate the idea by reference to some concrete examples that show that the counterfactual analysis is a step that comes before the legal qualification of the agreement as restrictive by object or effect. Here they are:

- Export prohibitions and Erauw-Jacquery: Typically, an agreement that provides for an export prohibition is restrictive by object. This is not always the case, however. Where the analysis of the counterfactual suggests that the agreement would not have been concluded in the absence of the export prohibition, it is not restrictive of competition, let alone by object. Erauw-Jacquery, which builds on Nungesser, is crystal clear in this regard.

- Joint tendering and objective necessity: Cyril Ritter, an academically-minded Commission official, has recently uploaded a very interesting paper on joint tendering (which he – rightly in my view – sees as a form of joint selling). It is wholly uncontroversial to say that joint tendering can in certain circumstances be restrictive by object (more debatable is whether such agreements are typically by object infringements).

What matters for the purposes of this post, in any event, is an important point that Cyril makes in the paper. Where the agreement is objectively necessary for the parties to take part in the tender, it does not restrict competition, whether by object or effect. As he puts it, ‘there is no competition to restrict’ in the first place, as the parties would not have taken part in the tender absent co-operation between them. - Price-fixing and collecting societies: The activities of collecting societies provide a wonderful example – if often forgotten – that a horizontal price-fixing agreement is not necessarily restrictive by object. Think about it: we are talking about an agreement whereby all the authors license their works jointly through a common platform. Is it a cartel? Certainly not. Price-fixing and all, this agreement falls outside the scope of Article 101(1) TFEU – and is thus not restrictive by object – where it is necessary for the collecting society to perform its function.

Competition under Article 101(1) TFEU means ‘competition that would otherwise have existed’

The Court clarified in Societe Technique Miniere that the word ‘competition’ in the context of Article 101(1) TFEU ‘must be understood within the actual context in which it would occur in the absence of the agreement in dispute’. In other words, ‘restriction of competition’ under Article 101(1) TFEU means ‘restriction of competition that would have existed in the absence of the agreement’ – as opposed to ‘restriction of competition that could exist in the abstract’.

There is nothing in Societe Technique Miniere, or in subsequent case law, that suggests that a difference must be made in this sense between restrictions by object and by effect. Such a distinction would in any event be artificial. The letter of the Treaty makes it clear that the notion of restriction of competition is a single one. And the Court has repeatedly held (AC Treuhand being a very good recent example) that no differences should be made where the Treaty itself makes no difference.

The object of an agreement cannot be understood without the counterfactual

If the analysis of the economic and legal context suggests that the agreement does not restrict competition that would have existed in its absence, it is very likely that its object is not anticompetitive. The rationale for the agreement (which is after all what the notion of ‘object’ is all about) is most probably a different one.

Allow me to come back to Cyril’s example: if the analysis of the counterfactual reveals that the parties would not have been able to submit tenders individually, the aim of the joint tender cannot be the restriction of competition. Most probably, such an agreement has a pro-competitive purpose, and it is certainly capable of making way for more effective competition (to come back to the expression used by the Court in Gottrup-Klim).

What explains the perpetuation of some myths and misconceptions?

Even though the case law is clear, the view that the analysis of the counterfactual does not apply to restrictions by object is still popular. Why? Because, I think, many people believe that the notion of restriction by object is something that it is not.

For many people, a restriction by object can be established in the abstract, that is, without examining the objective purpose behind the agreement and without considering the economic and legal context. According to this perspective, a price-fixing or market sharing agreement would always be by object infringements. This view is also misguided, and this is something that the Court has repeatedly held. It is true that, as pointed out in Toshiba, the analysis of the abovementioned factors may not be equally detailed in all cases, but this does not mean that the analysis can ever be established in the abstract.

Dear Pablo, inspiring thoughts, as always! I would say that it depends on what one understands by “counterfactual analysis”. What you point out here are certainly “counterfactuals”. But it is not the kind of fully-fledged effects-based analysis most people (or at least myself) would think of in terms of the counterfactual concept as commonly used. It is a difference to ask if there would have been competition between the parties (at all) in the absence of the agreement in question, or to ask what effects that competition would have had on the market.

Moritz Am Ende

21 March 2017 at 11:54 am

Thanks for a thought-provoking post. I agree with the above comment: the question is, what is a counterfactual analysis? If what you are saying is that a similar exercise needs to be done as in effects and merger cases (i.e. selecting a single hypothetical scenario, which is the most likely scenario to emerge absent the agreement/merger), then I’m not sure that would be appropriate for ‘by object’ cases.

The case law you describe seems to apply in particular to two separate concepts: legal and economic context and objective necessity. The analysis of the legal and economic context helps us determine whether absent the agreement, the parties to the agreement would have exerted competitive pressure on each other. That is not a full-on counterfactual analysis in the mergers/effects sense. In the analysis of the legal and economic context, it is not necessary to select the most likely counterfactual, but rather to determine whether or not a competitive relationship would have existed. The parties need not be actual competitors for this to be the case. Take for example the Power Transformers case, where the question was whether the Japanese and European competitors could have competed with each other, not if they would have competed.

So while there is indeed a need for analysing the competitive relationship that could have existed absent the agreement (because if one does not understand this, then how can one say it is restricted?), that analysis is not the same as a counterfactual analysis in an effects- or merger context, which has the aim of determining the scenario that is most likely to occur absent the agreement/merger. Such a determination is not necessary in an object case. For example, in a blatant price-fixing cartel that spanned five years, it is not necessary to do a detailed analysis of how competition would have developed absent the price-fixing agreement, it is only necessary to determine that the context is such that absent that agreement the parties exerted competitive pressure on each other (as actual or potential competitors), and that therefore absent the agreement prices would be set under competitive pressure.

The second point is objective necessity. Here, the authority only needs to prove other plausible ways of implementing the main operation without the restriction; it does not need to prove the single most likely counterfactual scenario that would have emerged out of the possible alternative scenarios. See recently the ASDA/MasterCard case in the UK, which defined an ‘ancillary restraint counterfactual’: “The ancillary restraint counterfactual can be one which might arise in the absence of the restraint, although it must be realistic” and “Thus the test for choosing the counterfactual for the purposes of the ancillary restraint doctrine provides a lower threshold for the regulator or other person complaining of a restraint than the test for choosing the counterfactual for the purposes of establishing a restriction of competition [by effect] within the prohibition of Article 101(1).”

SH

21 March 2017 at 3:03 pm

Thanks to both for your comments!

I do not believe we disagree. Applying the counterfactual to figure out the object of an agreement is not the same as establishing its effects. These are two different exercises (which I think SH summarises really well). By the same token, the fact that the evaluation of the effects of a practice also requires an analysis of the counterfactual does not mean that the nature and purpose of the exercise is the same at each stage.

SH: you identify the sort of counterfactual analysis that is required to make sense of the object of an agreement (objective necessity, ‘real concrete possibilities’). I guess my only question is whether, and why, you would object to it being called counterfactual. Is the objective necessity test not about figuring out what would have happened in the absence of the practice? The purpose at each stage is different, but this does not make it any less of a counterfactual. I fully agree, by the way, that, at the by object stage, a plausibility test applies. Again, you present it very effectively.

Pablo Ibanez Colomo

21 March 2017 at 4:54 pm

Thanks Pablo. I guess I don’t have a particular problem with calling it ‘counterfactual’, as long as it’s clear that this does not imply the same type of analysis/test as an effects case or merger (which we agree on)! My experience is that as soon as the word ‘counterfactual’ is used, people think this means an agency (or a claimant in a damages action) has to basically go through an effects-type analysis. As long as it’s clear that this is not the case, then I have no direct problem with using ‘counterfactual’. What’s in a name, right?

SH

21 March 2017 at 5:51 pm

I never really thought about it that way, but I guess yes, the ancillary restraints doctrine (and in particular the objective necessity part) is a sort of counterfactual analyis.

Moritz Am Ende

21 March 2017 at 7:12 pm

Hi Pablo,

Excellent post, as always. I agree with you fully. But I would be curious to read your views about the following scenario. Economists and lawyers do not always agree on this one:

Two pharmaceutical companies sell a drug to treat a particular illness. These are the only two suppliers available and each holds half of the market.

Both are investing significant R&D in a second generation drug that would be vastly superior to and fully replace the existing first generation.

The probability that either firm succeeds is 50% and independent of the success of its rival. Consequently there is ¼ probability that both simultaneously succeed.

However, if both firms succeed, future competition between them will wipe out expected profits (i.e. the ex ante R&D costs are greater than the future expected revenues). But if one firm succeeds and the other fails then the succeeding firm can charge a monopoly price and make a healthy profit. Let’s assume that expected value of investing is marginally positive. Hence a risk neutral firm would decide to invest and take its chances that the other fails. However, let’s assume a risk averse firm would place more weigth on the possibility of failure and would choose not to invest.

The two firms enter into an agreement to fix a floor on prices for the future drugs (say a price below the monopoly price but above the duopoly price). This agreement restricts competition between them but they advance a “counterfactual “ defense. Namely, they claim that they are both risk averse and in the absence of such agreement neither of them would invest and hence no 2nd generation drug would be developed.

Each firm hires economists demonstrate it is risk averse (note risk aversion is an objective and measurable economic concept).

Is the counterfactual defence valid in this case? Would it be in accordance with the case law if this price-fixing agreement falls outside of 101(1)? Can such determination depend on a hard to assess, yet objective variable, such a firm’s tolerance for risk? Should instead the authority presume that all firms are risk neutral?

Consider also this extension that helps to illustrate the difference (but also the inextricable link) between a counterfactual defense (i.e. agreements does not fall under 101(1)) and a 101(3) defense:

Note price fixing ensures that both firms, even if risk averse, will continue to invest in developing the new drug, but not that one or both will succeed (this is still 75%): But assume further that part of the knowledge acquired by one firm spills over and hence increases the probability that the other firm succeeds from ½ to 2/3. Now the chance that at least one firm succeeds increases to 89%. Hence, indirectly, price fixing increases the chance that society benefits from the successful development of the new drug, by at least one firm, if not both. What do you think? Is this a “counterfactual” defense or an efficiency defense?

Relative to a possible scenario in which no firm succeeds this could be considered as the former. However, I am more inclined to consider it an efficiency defense since the possibility of the drug being developed in the absence of the agreement already exists – the agreement just makes it more likely, because it ensures that even risk averse firms would take their chance and invest. But clearly what view one takes matters a great deal because the conditions under 101(3) are pretty onerous – though I believe could be met in this case.

—

and a bonus teaser: Imagine, as is often the case that the only buyer is the national health service? Should this make any difference in the determination of whether the price fixing is a restriction of competition and/or whether, if so, it is an object restriction? I suspect many legal scholars would argue it should not since even a monopsonist facing two suppliers will have to pay a higher price if the suppliers fix the future price

However, note that this example is very similar to a monopsonist buyer committing to purchase the second generation drug at a fixed price above the duopoly price, in order to give an incentive to both to continue to invest*. Presented in this “context” it becomes clear that the buyer stands to benefit and prefers to pay a higher future price to increase the chance that there is a second generation drug in the market. This now seems less objectionable. But the way the problem is framed leads to opposing intuitions. This is problematic if one follows these intuitions and wants to ensure legal certainty, which depends on consistency of enforcement in closely related situations.

*(one notable difference is the enforceability of the monopsonist’s commitment relative to the enforceability of the price-fixing agreement – but if enforceability is not a problem both scenarios are largely identical).

miguel dlm

27 March 2017 at 5:35 pm