Finding the appropriate legal test in EU competition law: on presumptions and remedies

There is not a single legal test in EU competition law.

Some practices are deemed prima facie lawful, and other practices prima facie unlawful irrespective of their effects. In between, there is conduct subject to a (standard) analysis of effects. As I explained recently on the blog, there is yet another category of practices; these are subject to an ‘enhanced effects’ analysis. By ‘enhanced’ I mean that it is necessary to provide, at the very least, evidence of indispensability before intervening.

I like to think of the applicable legal tests in EU competition law as discrete points along a spectrum.

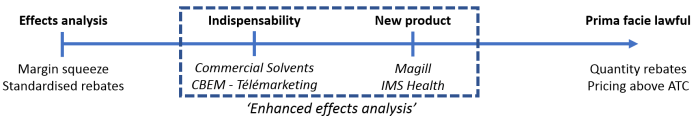

This is what the spectrum looks like under Article 102 TFEU:

It makes sense to zoom into the right end of the spectrum, which is a bit crowded. It looks like this:

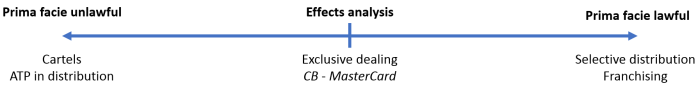

This is what the spectrum looks like under Article 101 TFEU (ATP stands for ‘absolute territorial protection’ in case you are wondering):

One question that keeps me busy (and which I discussed, inter alia, in Ithaca and Vilnius) is why and how the Court of Justice chooses the applicable legal test in individual cases. Why is some behaviour deemed prima facie lawful? Why is the enhanced effects analysis chosen for some practices but not for others?

The question is important, and the answer not immediately obvious. For instance, leveraging conduct is not subject to a single legal test under Article 102 TFEU. ‘Leveraging abuse’ is not a legal test. These words do not say anything about the conditions under which a given practice is deemed abusive.

In some instances (e.g. tying), leveraging is prima facie unlawful irrespective of its effects. In other instances (e.g. refusal to deal), it is subject to an enhanced effects analysis. What explains the disparate treatment of the various leveraging strategies?

I found the question interesting for other reasons. For instance, the Court has been criticised for applying different legal tests to refusals to deal, on the one hand, and ‘margin squeeze’ practices, on the other. The latter are subject to a standard effects analysis whereas the enhanced effects analysis applies to refusals to deal. Could it be that the Court has a point in spite of the criticisms? Spoiler alert: I believe it might.

***

Why are some practices prima facie unlawful under both Articles 101 and 102 TFEU?

The case law suggests that a practice is deemed prima facie unlawful irrespective of its effects – i.e. it is a by object infringement – where:

- It is presumed to serve no purpose other than the restriction of competition; and

- It is presumed to be capable of having restrictive effects on competition.

Intel (in the context of Article 102 TFEU) and Murphy (in the context of Article 101 TFEU) make it clear that firms can always provide evidence to rebut the presumption of capability.

Why are some practices prima facie lawful? I can identify two instances in this sense:

- Where the practice is objectively necessary to attain a pro-competitive aim (think of Metro I, Coty, Pronuptia and so on as clear examples); or

- Where the effects would not be attributable to the practice. For instance, the effects of above-cost price cuts are not attributable to the dominant firm, but to rivals’ inefficiency.

And finally: why is it that sometimes the Court of Justice has required an enhanced effects analysis? And why, for instance, is the enhanced effects analysis required in refusal to deal but not in ‘margin squeeze’ cases?

It all has to do, I believe, with the remedy. One needs to turn the analysis on its head and start by figuring out what intervention might entail in practice.

The standard effects analysis applies where the remedy is reactive in nature – a one-off obligation not to do something. These are instances in which a cease and desist order can effectively deal with the issue (no monitoring, no complexity with the implementation and/or with compliance).

The enhanced effects analysis applies where the remedy is proactive – that is, where it amounts, directly or indirectly, to imposing positive obligations on firms (a requirement to do something). These are instances in which the remedy comes with all sorts of potential difficulties (related either to the design, the implementation or the monitoring of the obligations).

The Microsoft I case (and, more precisely, the obligation to supply interoperability information on FRAND terms) is a good example of proactive enforcement. Determining the fair price of interoperability information is incredibly complex. So much so, in fact, that the Commission left it for the firm to figure out.

Against this background, one can understand why the Court may have deemed it justified to differentiate the legal treatment of refusals to deal and ‘margin squeeze’ practices.

A ‘margin squeeze’ can be effectively addressed through reactive intervention. Dealing with an abusive refusal to deal, on the other hand, is much more complex. One has to determine (directly or indirectly) a wholesale price, and then monitor compliance with the remedies on a lasting basis.

In cases like Commercial Solvents, Magill or IMS Health, the Court may have felt that the complexity of the remedy justified raising the substantive bar. The remedy, accordingly, is not an afterthought, but a key question that informs substantive analysis.

Ordering a company to resume supplies with a rival, to start licensing its intellectual property or to change the design of its products (as in the Internet Explorer case) can go wrong for several reasons – this is where I generally crack my joke about Richard Whish being probably the only person with a version of Windows without the Media Player.

If this is true (which it is), it makes sense to confine to exceptional circumstances the instances in which these remedies may apply.

I would say more: looking at the remedy to identify the appropriate legal test is a much more meaningful exercise than all other attempts to distinguish between categories of practices.

Instead of using more or less artificial labels and discussing whether one label is more appropriate than another, it makes sense to look at what remedial action may involve in practice, and infer the legal test from this exercise.

As ever, I look forward to your thoughts!

Prof Colomo, thank you for your very useful post. I generally agree that positive obligations should be justified by an ‘enhanced effects’ analysis.

Could one exception to your principle be where the intellectual property is already encumbered by a FRAND committment? I think that a case can be made that reneging on a FRAND prior commitment (Samsung, Motorola) could be prima facie unlawful (on exploitative grounds) or at least subject to normal effects analysis even though the remedy would be to require the firm to license on FRAND terms. (This is, of course, because the standardisation process arguably conferred the patent significant market power in exchange for the FRAND commitment).

Then again, this is probably not a true exception to your principle as the remedy there can be thought to be reactive as well, i.e. to desist from breaching the prior FRAND commitment.

Jrlow

2 November 2018 at 6:30 pm

Dear Pablo, as usual I find your concise post to provide more clarity than certain (many), much longer articles or speeches (though I know for sure your thoughts are the result of extensive researches and studies on long academic texts – and of a lot of listening). Nonetheless, I would like you to write less of these posts (yes – less not more) b/c I cannot refrain to immediately read them (and sometimes comment) even when I’m plenty of more urgent staff to do (just as now).

I very much agree with your point: it’s the required remedy that explains and creates the dividing lines between certain practices with regard to the legal test to be applied. Prohibiting a refusal to deal, for instance, also entails an obligation to deal or to enter into a contract, which is very exceptional in private contract law (and very controversial if not expressly provided for by law). On this prong, just let me add that a distinction should also be drawn (as it is by case-law, including by the CJEU) between refusal to continue an existing deal (e.g to supply a product to an existing customer) and refusal to deal something competely new and never conceded to anyone before. The second instance, of course, requires a super-enhanced analysis of effects (essential facility + elimination of all competition or new/enhanced product test, similar to what is required for IP rights); whilst the first instance may require mere “indispensability” for effective competition to continue being as effective (or for an effective competitor to continue be as effective? Not so

clear-cut to me), without being necessary to substantiate an essential facility. However, nowadays the concept of “fairness” in competition law may blur this distinction, particulalry when applied to the digital environment (platform dynamics), where e.g. in the Google and Android cases we see an essential-facility-type remedy without the Commission having deemed necessary to substantiate an essential facility (we will see what the CJEU wilm say about that). Indeed, strong networks effects in data intensive and sensitive sectors (almost all these days) may make the existance of “essential facilities” much less exceptional and unique within a specific industry as it used to be in the “analog” world.

This said (to what I’d like to read/listen any feedback from you), I was caught by the point where you state that where the (restrictive) effects cannot be attributed to the practice, the condict should be held per Prima facie lawful (which means that the couterfactual would show the same effect). I wonder: how can you properly establish the counterfactual without analysong effects? Is first-glance analysis ever sufficient to this end? Or rather in most cases one still needs at least a standard effecy analysis to this purpose?

Thanks for sharing and best regards!

Enzo

enzomarasa

2 November 2018 at 6:47 pm

Thanks for a very interesting blog post!

I am wondering, if what you are saying – that the remedy determines the legal test – is correct, what impact does that finding have on the Commission in its enforcement practice (both with regards to procedures chosen and the reasoning in decisions)? How, in your opinion, does or should the Commission adjust its enforcement policy with a view of ensuring it does not get its decisions quashed by the Court?

Katharina

5 November 2018 at 2:56 pm

Thanks for an interesting blog post! I would however argue that the difference between a margin squeeze and a refusal to deal lies not in the complexity in crafting effective remedies but in that it is much more intrusive for a competition authority to meddle with the freedom to choose ones trading partner (refusal to deal) than to alter the terms on which one trades (margin squeeze).

Pamela

5 November 2018 at 3:13 pm

Richard Whish only has a copy of Windows without the media player because Microsoft gave him one!

Richard Whish

5 November 2018 at 10:49 pm

Haha, which would only prove my point!

Pablo Ibanez Colomo

6 November 2018 at 8:43 am

Thanks everybody for your thoughtful replies!

Jrlow mentions FRAND and IP licensing: I would say the enhanced effects analysis applies by definition in these cases. After all, they are about standard-essential patents. Intervention will thus need to meet a threshold of indispensability.

Enzo asks whether the counterfactual can be established without an analysis of effects. Certainly! Experience and economic analysis can get you a long way. Pronuptia and Remia, for instance, are based on the counterfactual, and there is not a hint of an effects analysis in these cases. E.On Ruhrgas is there to tell you that, by looking at the regulatory framework, you can get a pretty good sense of the counterfactual: if regulation makes it impossible to enter the market, you can safely conclude that no competition would have existed in the absence of the agreement.

Katharina: your question is fairly complex, and — this is not shameless self-promo — tried to give some answers in my book. As you see, I observe that the Commission has used a variety of strategies!

Pamela: I believe we agree. Yours is just a different way of advancing the same idea. More intrusive intervention inevitably leads to more intrusive — proactive — remedial action.

Pablo Ibanez Colomo

6 November 2018 at 8:56 am

Thanks, Pablo! Totally agree that the counterfactual doesn’t require analysis of effects when the regulatory framework is sufficient to establish it.

All the best,

Enzo

enzomarasa

6 November 2018 at 9:13 am

Very interesting post. Of course, it ties in well with standard law and economics literature. Stigler’s Crime and Punishment already takes account of the costs of intervention, and a complex remedy increases those costs (both public and private). And coincidentally, it works very neatly with the points you made regarding Google Android – where, as you predicted , the remedy leads to very real private costs.

HK47

15 November 2018 at 9:37 am

Thanks for your blog, I enjoyed reading it! If you are passionate about legal tests, you may like my article in ECLR (Vol 39, Iss 10). My approach is a bit different: I try to develop a test for what a ‘competition restriction’ should imply. I think I share your wish to grasp, as I interpret it, what the decisive trigger is/should be for rendering conduct unlawful cf. competition law. Anyway, looking forward to your next post. Kind regards, Mart Kneepkens,

Mart Kneepkens

23 November 2018 at 11:38 am