Archive for October 2020

A symposium on ‘Big Tech & The Digital Economy’, by Nicolas Petit: Part II

As promised, here comes the second round of contributions to the symposium devoted to Nicolas Petit’s Big Tech & The Digital Economy, with yet another stellar line-up of scholars.

We very much hope you enjoy it as much as the first one. Today’s pieces are:

Competition Policy at the Crossroads: Similar Questions, Different Answers, by Andriani Kalintiri

Recalibrating Competition Law, by Giorgio Monti

Petit’s Cat: Uncertainty, Dynamic Competition, and Conglomerates, by Julian Nowag

A symposium on ‘Big Tech & The Digital Economy’, by Nicolas Petit: Part I

Nicolas Petit, founder of Chillin’ Competition, has recently published (with Oxford University Press) his long awaited volume, in which he discusses the ‘moligopoly scenario’ (see here).

Having read some earlier drafts, I can say that Nicolas, as a genuine academic entrepreneur, was not afraid to take risks: a lawyer by training, he ventures beyond his comfort zone and comes up with something of a hybrid for which there are no clear precedents.

Nicolas had the idea of organising a mini-symposium on his book. He has brought together an impressive group of European scholars, who have drafted their blog post-style reflections on the monograph.

Chillin’ Competition will be presenting these contributions in two instalments. This first features the following:

How do you solve a problem like Maria Big Tech?, by Pınar Akman

LaTeX Antitrust, by Thibault Schrepel

Big Tech and the Digital Economy: the muddled middle in a polarized debate?, by Anna Gerbrandy

Regulating digital platforms: the last dance of antitrust?, by Giuseppe Colangelo

Enjoy! More contributions next week.

The Old New Competition Tool ?

For around 10 years (between 2004 and roughly 2014) the competition community spent countless hours discussing how commitment decisions could pursue stretched theories of harm and obtain remedies that went well beyond what would have been possible in standard infringement decisions. By the way, I gave an overview of all this in this 2014 presentation (Lamadrid- Overview of competition decisions).

Commitment decisions (after Alrosa) probably made us all think that intervention under competition law could reach where it had not reached before. The Commission was able to intervene very effectively in many markets with forward-looking, far-reaching remedies agreed by the parties. This improved the functioning of many markets and arguably reduced clarity in the law. We became accustomed to remedies that were not necessarily proportionate to the concerns triggering investigations.

In the past few years, however, recourse to commitment decisions has become relatively rare. A positive aspect of the new enforcement trend was that infringement decisions and subsequent Court judgments would provide greater clarity on the law. Perhaps we did not anticipate that greater clarity as to where real boundaries lie might also lead to frustration which, in turn, would propel calls to replace the law and bypass Courts, but that is another story (or is it?)

Coincidentally, as the use of commitment decisions started to decline, the debate completely shifted. We suddenly discussed less about the far-reaching scope of competition law, and more about the alleged insufficiency of competition law. There may not be causality, but there is certainly some correlation. [Btw, it’s amazing how the world, incluiding competition law, has changed in these past 6 years].

One of the main reasons that made Art. 9 commitments less popular is that they could not lead to the imposition of fines, let alone huge fines. But, contrary to what used to be the case, proponents of more aggressive antitrust enforcement now argue that large fines are meaningless and don’t do the job, and that it’s only remedies that matter. From this perspective, at least, perhaps commitment decisions did the trick after all?

Others, including myself, were not necessarily in favor of commitment decisions becoming the standard enforcement tool because that would lead to all actors operating in the shadow of the law, not really knowing what the real law was. Commitment decisions, however, were case-specific, evidence-based, preliminary assessments, followed existing procedures and entailed a somewhat “participative” process, including negotiations with the affected companies and market tests). The Commission was also very smart in using commitment decisions while ensuring legal certainty in parallel infringement decisions (see e.g. the Samsung and Motorola decisions on SEPs, or the Visa and Mastercard decisions on MIFs). One could argue that commitment decisions already addressed some of the concerns voiced out against the new tool under consideration (a single instrument combining the NCT and the ex ante regulatory instrument).

Some might also argue that commitment decisions were also too slow. But were they? It would be interesting to explore the reasons why some cases dragged on for longer, and whether that may have been related to external factors and third-party strategies.

It might also make sense to spend some time negotiating remedies in advance, rather than impose impractical remedies that might then need to be continuously reviewed and updated. As the Commission itself explained, “due to the more consensual mode of concluding the case, the commitment path may result in more efficient proceedings and more effective remedies; it allows for a more fine-tuned tailoring of the commitments and swifter implementation”. In a way, this was participatory antitrust avant la lettre.

Be that as it may, the welcome revival of interim measures should dispel or alleviate timing concerns. The recent Broadcom case is the perfect example.

The history of EU enforcement under Article 9 is, from the authority’s standpoint, an unquestionable story of success. It allowed for rapid, strong and far-reaching intervention subject to fewer constraints than in standard cases. By the Commission’s own admission, having companies give their views in the process also ensured that remedies were workable and reduced the risk of disproportionate / undesired outcomes. Perhaps commitments were not entirely satisfactory for anyone (authorities and rivals could want more, affected companies would want less) but that is probably why the tool resulted in an equilibrium that worked well. Commitment decisions did require the Commission to show that it could build a prima facie credible case (credible enough, at least, to force a company to make concessions to avoid the risks and harms that come with prolonged investigations), but that was not a problem, rather a safeguard to mitigate discretion.

Take a look again at the theories of harm pursued in Art. 9 cases and at the remedies that the Commission was able to obtain (summarized in slides 6-7 of the 2014 presentation). Does it feel like there was an enforcement gap? There also does not seem to be any dissatisfaction as to the outcomes that were secured by virtue of commitment decisions.

The Commission’s successful intervention in the Broadcom case shows that commitment decisions (combined with interim measures in the face of genuine risks of irreparable harm) could actually be the old new competition tool that many were looking for. I guess sometimes we want new things, perhaps forgetting that what we already have might be even better.

[Disclosure: I have no professional interests in, and no detailed knowledge of, the Broadcom case. I do have clients that could be affected by the new digital enforcement tool under consideration (full disclosures are available in my posts on those, see notably here). Like practically all competition practitioners, I also have a very large number of clients that could be potential addresses of commitment and/or interim measures decisions].

Remedies in Google Shopping: a JECLAP symposium with Marsden and Graf & Mostyn

It is remarkable that the remedies in Google Shopping, a case that was decided more than three years ago, are still being discussed. As you certainly remember, the Commission chose a ‘principles-based’ approach that did not specify a particular way to comply with the decision.

Complainants argue, to this day, that Google’s implementation of the neutrality obligation mandated by the Commission does not respect the principles outlined in the decision.

It is against this background that the Journal of Competition Law & Economics is proud to feature a mini-symposium on the matter.

One of the papers – ‘Google Shopping for the Empress’s New Clothes –When a Remedy Isn’t a Remedy (and How to Fix it)’ – was prepared by Philip Marsden. As disclosed by Philip, the piece is a spin-off of some research he undertook for one of the complainants in Google Shopping.

The second paper – ‘Do We Need to Regulate Equal Treatment? The Google Shopping Case and the Implications of its Equal Treatment Principle for New Legislative Initiatives’ – was prepared by Thomas Graf and Henry Mostyn, who represent Google in the case (as is well known and disclosed).

The two papers are currently behind a paywall but we are looking, at JECLAP, to making them available free of charge soon.

If you ask me, the key takeaway about this debate is the very fact that it is taking place and that the remedy is still in a limbo over three years since the adoption of the decision.

Contrary to what has sometimes been suggested, this state of limbo is not a bug. It is an integral feature of proactive intervention in digital markets. Redesigning products and altering business models is complex, prone to errors, and does not have an obvious end in sight (once down this road: where to stop?).

I certainly do not see this case as a one-off or an aberration, but a sign of the challenges to come under the new competition law. As I mentioned at a conference a few weeks ago: in digital markets finding an infringement is not the end, it is just the end of the beginning.

Enjoy the papers!

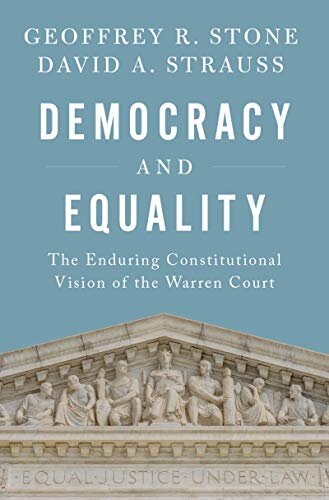

Democracy and Equality: on the US Supreme Court and the role of judges

The US Supreme Court has been all over the news recently. Unfortunately, this was so because of the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a most remarkable figure whose reputation and achievements were admired outside the legal world and whose legacy will inspire many.

If it precisely because of legal minds like Ruth Bader Ginsburg that the US Supreme Court is, and has always been, a fascinating institution. As I was reflecting on her passing and the implications, I was immediately drawn to a book published earlier this year and which I read during the worst of the lockdown.

The book is called Democracy and Equality and is published by two renowned US constitutional law scholars. I very much recommend it if you feel like venturing outside competition law: it is particularly well written and accessible; more importantly, it is a thoughtful reflection of the role of courts in a democracy.

Democracy and Equality provides an overview of the landmark opinions of the so-called Warren Court (1953-1969), which advanced civil rights and liberties, as well as equality, probably like no other in the history of the US Supreme Court.

This is the Court that delivered Brown v Board of Education (on the segregation of public schools), Miranda v Arizona (on the right of suspects to remain silent and to be advised by an attorney), Reynolds v Sims (where it upheld the ‘one person, one vote’ principle) and NYT v Sullivan (on freedom of speech and my personal favourite in what it achieved in holding power to account and effectively ending segregation).

The book is particularly valuable, in any event, in that it uncovers the single, unifying vision of the Warren Court and its role in the institutional structure of which it is a part.

The authors convincingly explain, and the cases discussed show, that the members of the Warren Court understood that their role was to correct the inevitable flaws and inequities that come from majoritarian institutions. In the same vein, they interpreted the US Constitution as a device that provided protection for minorities against the proverbial tyranny of the majority.

Thus, if the Warren Court was ‘activist’ (a favourite word of its critics), it was so in a very precise way and for a purpose that was more noble than simply contributing to the growing polarisation surrounding us.

I know we are all busy, but enjoy the book if you can (it reads in an afternoon). And if it leaves you hungry for more, The Nine is another exceptional book that covers another crucial period of the Court.

IEB Competition Law Course (24th edition)- Now online!

The 24th (!) edition of the competition law course that I co-direct at the IEB in Madrid will take place online. The course (taught partly in Spanish and partly in English) will run from January to March 2021. All lectures take place in the afternoon (16h to 20h) in order to help make it compatible with other professional or academic activities.

As always, it will feature a great line-up of international lecturers that include Judges, officials from the European Commission and other national competition authorities as well as top-notch academics, in-house lawyers and practitioners. This includes Pablo, who will coordinate two modules and take care of the introductory session. Students are tipically officials from competition authorities, in-house counsel wishing to get a deeper understanding of competition law as well as young lawyers/economists. The course is designed to cater to all levels.

While the pandemic will not allow us to travel to Madrid, the online format will enable us to access a wider pool of interested professionals. The full course has a cost of 2,000 euros, and it is also possible to register for individual modules or seminars.

This is the general* program

(*There will be detailed individual programs for every module and seminar, each of which will feature a variety of experts)

Introductory session (15 January- afternoon). Cani Fernández (President, CNMC) and Pablo Ibañez Colomo (LSE, CoE)

Module I – Cartels and procedure (18-20 January-afternoon). Coordinator: Isabel López Gálvez (CNMC)

Module II – Other agreements and restrictive practices: vertical and horizontal agreements (25-27 January- afternoon). Coordinator: Carmen Cerdá Martínez-Pujalte (CNMC)

Seminar 1- Recent Developments in EU Competition Law (5 February 2021). Coordinators: Fernando Castillo de la Torre and Eric Gippini-Fournier (Legal Service, European Commission)

Module III- Abuse of dominant positions (8-10 February- afternoon). Coordinator: Pablo Ibáñez Colomo (LSE, CoE)

Module IV – Merger Control (15-17 February- afternoon). Coordinator: Jerónimo Maillo (USP-CEU)

Seminar 2 – Competition Law in Hi-Tech Markets (26 February). Coordinator: Nicholas Banasevic (DG Comp, European Commission)

Module V- Sector Regulation and Competition (1-3 March-afternoon). Coordinator: Pablo Ibáñez Colomo (LSE, CoE)

Module VI – Public competition law: State aid and Public undertakings (8-10 March 2021- afternoon). Coordinators José Luis Buendía (Garrigues) and Jorger Piernas (University of Murcia)

Seminar 3 – Private enforcement of the competition rules (19 March 2021). Coordinator: Mercedes Pedraz (Magistrada, Audiencia Nacional)

We will also be holding three practical workshops dealing with inspections, distribution agreements and mergers.

If you want to know more, please drop us a line at competencia@ieb.es

To Comment or not to Comment on the Ex Ante Rules for Gatekeepers (+ 9 Other Questions on the Draft Proposals)

Until today, I had avoided commenting publicly on the ex ante regulatory instrument that the Commission is considering for “platforms acting as gatekeepers”. There were three reasons for this. First, unlike the New Competition Tool, I did not see this initiative as a threat to competition law as we know it. Second, I do understand that there is a certain public anxiety about digital markets (to some degree justified, to some degree exaggerated by interested stakeholders), and a margin for regulation to legitimately address that anxiety and improve things. Third, my opinions could be legitimately criticized as biased because an important part of my work is to advise and represent companies targeted by this initiative. My thinking was that there were already enough people with professional interests making noise in all directions for me to contribute to the cacophony.

Alas, my reasoning on those three fronts has changed after reading the bold leaked drafts that circulate widely since last week. First, I now see a risk that the ex ante rules might have a much greater impact on competition law than I had anticipated. Second, it seems that the current plans might not always be addressed at the issues causing public anxiety, but to a large extent target issues at the core of pending competition cases. Third, I will not falsely pretend my opinions are neutral, but I hope they might add some value to the debate. Experts working against my clients have also authored some of the influential reports that the leaked documents cite as evidence supporting the need for intervention and, to be sure, I don’t think their views should be disqualified. In addition, given that the rules appear to be crafted to affect only a remarkably limited number of services, it is likely that a majority of stakeholders will feel relieved and/or might not have incentives to voice out concerns, so you might not be exposed to many contrarian views. And even if you are, a lot of the commentary out there seems somewhat radical.

As in other matters, there is excessive polarization here, and even a tendency to look at things through myopic and binary (progressive vs conservative) lenses. Some partisans of regulation invoke “progressive” attitudes as a reason to favor these initiatives. Others claim that they oppose them in line with “conservative” principles. In reality, though, this debate has very little to do with politics. There are media companies who support Trump, Brexit and deny climate change that also support these initiatives (provided they only target their rivals, of course). There are also conservatives who want more regulation and antitrust intervention (even if arguably not always for the right reasons; e.g. at a recent antitrust hearing a Republican Congressman claim Google should be regulated because it favours WHO health advice over Trump’s…). And then there is a vast majority of other perfectly reasonable companies or stakeholders who have legitimate commercial/professional interests in these initiatives passing, or not passing, regardless of politics.

Instead of simply shouting “this is great” or “this is rubbish”, I’ll try to reason my concerns through. Confronting (hopefully) reasonable views should (hopefully) contribute to progress. The public debate should not belong only to those shouting the most (and you should see my Twitter feed…). I said before that we can do better, and I will try to play my part by being assertive, but as constructive as possible. It is not easy to decide where to start, but here are some questions:

1-.Why The Focus on 4 Key Services? The current drafts indicate that the broader options have already been discarded, and that the plan is to focus only on 4 companies “key services”, namely “online intermediation services (market places, app stores and social networks), (ii) online search engines, (iii) operating systems and (iv) cloud services”. Queries: What were the criteria to concentrate on these? Can other “information society services” be excluded from the potential scope of application of the rules, even in the presence of “gatekeeping” features? Are these the services of the economy where consumers are getting the worst deal in terms of price/innovation/quality/R&D investment? Are these the services with the greatest risk of consumer lock-in or with the highest switching costs? Are these services that have escaped competition law scrutiny? Or are these the intermediary services that have succeeded in creating greater opportunities for third party business users?

2-. Unavoidable = Indispensable = Market Power? Perhaps the questions above are irrelevant, because the drafts show that the concern is that some services may be “de facto unavoidable for business users”. That does not necessarily mean the initiative is less legitimate, but it raises questions worth asking. Queries:

· The assessment of market power depends on the competitive constraints faced by the company under examination. Under this alternative standard, however, “gatekeepers” subject to these rules would be identified judging solely from the perspective of whether (all? some? how many?) business partners have (other? equally convenient?) alternatives, regardless of the possible exercise of market power. Should that be the right approach? Should we adapt our thinking about identifying market power, or should we only make a carve-out for these 4 services? And if the concern is not market power but the “economic dependency” of certain users, can the proposed remedies go beyond that and constrain, for instance, product design decisions?

· Does “de facto unavoidable” mean the same as indispensable within the meaning of EU Law, also beyond competition? Consider, for example, paragraph 55 of the recent CJEU Airbnb ruling. Would accomodation intermediaries, for example, be covered by these ex ante rules in spite of the Court’s observations?

. Rather than simply identifying “key services” and designating them as “gatekeepers” (which could arguably risk looking like reverse-engineering), would it make sense to craft some sort of normative or objective criteria to decide whether a given service might have “gatekeeper status” (e.g. on the basis of market shares, shares of traffic or other objective parameters)? What would be the process to identify the services with gatekeeper status? Would companies have opportunities to make their views known? Should there be consultations like in telecom? How often would this status be reviewed?

3-.A Gap in Competition Law or An Overlap With Competition Law? I had the impression that the ex ante rules would cover matters falling outside the scope of competition law, and that this is what could lend legitimacy to the initiative (competition law is not everything after all). I was wrong. The list of “black” and “grey” practices in the leaked documents cover three categories: (i) data practices; (ii) self-preferencing; and (iii) tying and bundling. The practices in the list pretty much coincide with the same very practices that the Commission and NCAs have recently investigated, or are currently investigating, in cases concerning mainly Amazon, Apple, Booking, Facebook, Google and Microsoft.

This means that (unless the EU Courts rule otherwise), this is all conduct that currently falls within the scope of the competition rules. Some of the practices in the draft lists in fact contain the actual wording of some of the examples included in Art. 102; others reproduce the wording and terminology used in recent decisions. Queries: To the extent that the rules would apply to practices falling within the scope of the competition rules, and only to companies that the Commission believes are dominant, then would this initiative fill a gap? Or would it rather replace case-by-case evidence-based assessments by outright bans when it comes to a handful of companies? Given the clear overlaps, wouldn’t it make sense for the enforcement of these rules to sit with DG Comp in order to ensure consistency with existing enforcement tools and with a possible NCT?

4-. Why Now? The Commission has spent years building cases, presumably challenging what it considers to be the most egregious instances of “black-listed” conduct. It is perfectly reasonable for the Commission to build its legislative proposal on “evidence derived from competition enforcement practice” as the drafts seek to do. But shouldn’t we then wait until those cases are over? The Commission has often said that what lends legitimacy to the fact-finding and enforcement process is judicial review. And EU Courts have now been called to render Judgments assessing the effects of some of these practices on the basis of actual evidence. Queries: Would upcoming Judgments concerning practices in the black list be rendered irrelevant before they are decided? Would that be that an unintended consequence? Would that be good thing? Would we accept this process in all areas of the law, or should we have an exception for matters that affect only a few companies? Would regulation be better or worse if it were also informed by the findings of the Courts in relation to the cases brought by the Commission?

5-. Harmonization as the Goal? According to the leaked documents, “the objective of the intervention is to harmonise rules in Member States relating to unfair behaviour in gatekeeper platforms”. Query: To the extent that competition laws, unfair competition laws, the P2B Regulation, and other initiatives at the national or EU level would remain in place, would the ex ante rules harmonize national legislation or would they rather be adding one more tool to the toolkit?

6-.What About the NCT? If these rules were to enter into force, an NCT would arguably not add much value with respect to these 4 “key services”. Most people thought, however, that these were precisely the services that an NCT would target. Query: Does this mean that the NCT will be deployed mostly in relation to other services?

7- The “black list”. The list is “based on CNET/GROW” evidence gathering. The legitimacy of the initiative would arguably be enhanced if that evidence were identified and made public. As explained above, it would appear that most of the practices in the black list target conduct at the core of recent or pending cases. It is commonly accepted that many of those practices (e.g. MFNs) are competitively ambiguous; they might have pro- or anti-competitive implications depending on the circumstances. Not even complainants in “self-preferencing” cases argued that self-preferencing should be prohibited in all circumstances. The drafts recognize that this practice is widespread and states that “in offline situations, such behaviour is not generally considered anticompetitive”. Queries: Should practices like self-preferencing be treated differently in offline vs online situations? Are practices included in the black list because (a) there is evidence that procompetitive aspects disappear, or are always outweighed, (only) in relation to these 4 key services/companies?; or (b) we can’t be bothered to assess this question in relation to the 4 key services/ companies?

8-. The added value of the “grey list”? The grey list contains a list of practices “where intervention by the competent regulator is required”. Query: Would intervention in these cases take place through standard procedures (e.g. a competition investigation?) subject to established standards? The merit of a grey list may arguably streamline and accelerate the process and could provide some sort of ex ante guidance, but then again, which would be the competent regulator? Given the clear overlaps with possible competition cases (and the need for coordination with national authorities), wouldn’t it be preferable for DG Comp to be in charge of enforcing the rules? That would also enable the Commission to coordinate with national authorities through tested channels like the ECN.

9-. Are you trying to say that there is nothing to do and that we should never regulate? Not at all. There is probably merit in the idea of having some sort of ex ante rules. The digital economy, like any sector of the economy, needs rules. Like in any sector of the economy, rules should be objective, not subjective, and a result of careful evidence-based reflection. Rules do not need to be only (or mostly) about efficiency, there are certainly other higher values. Rules can and should change, they can be creative; they can go against precedents and even be harsh when needed. But they should ideally be sensible, they should benefit the most (not the few), and they should be crafted to pursue their goals while minimizing the risk of undesirable outcomes. Leaving room for nuance and flexibility is often wise, particularly in the case of forward-looking rules. It would be a mistake to craft these rule to target only specific practices seen so far, because these will also be the applicable rules for future platforms. As Pablo explained in a previous post, building on the experience acquired in telecoms, a business-neutral, principles-based regime and the possibility of case-by-case assessments would seem much more flexible, adaptable and sensible than the alternative “black list” approach.