The Italian Competition Authority in Enel v Google: will Bronner and Magill survive common carrier antitrust?

Earlier this month, the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM) adopted a remarkable decision, which deserves close attention, in a dispute involving Enel (the Italian incumbent in the electricity sector) and Google. You will find the decision here (in Italian) and a press release (in English) here.

The decision stands out from others in the digital sphere in that it is expressly framed as an outright refusal to deal. While in other cases it is genuinely open to question whether the ‘exceptional circumstances’ tests laid down in Magill and Bronner are applicable, there is no doubt on this point in Enel v Google. The complainant requested access to Android Auto and the authority applies the case law on refusals to deal.

That Magill and Bronner provide the relevant tests is also clear in light of Slovak Telekom. Intervention in Enel v Google amounts to requiring the defendant to redesign its product. On this point, the decision goes beyond an obligation to negotiate access with a would-be rival, which is the typical remedy in a refusal to deal case. The Italian authority has asked Google to release a version that can accommodate the functionalities of Enel’s product.

What is the case about? Android Auto and Enel’s JuicePass

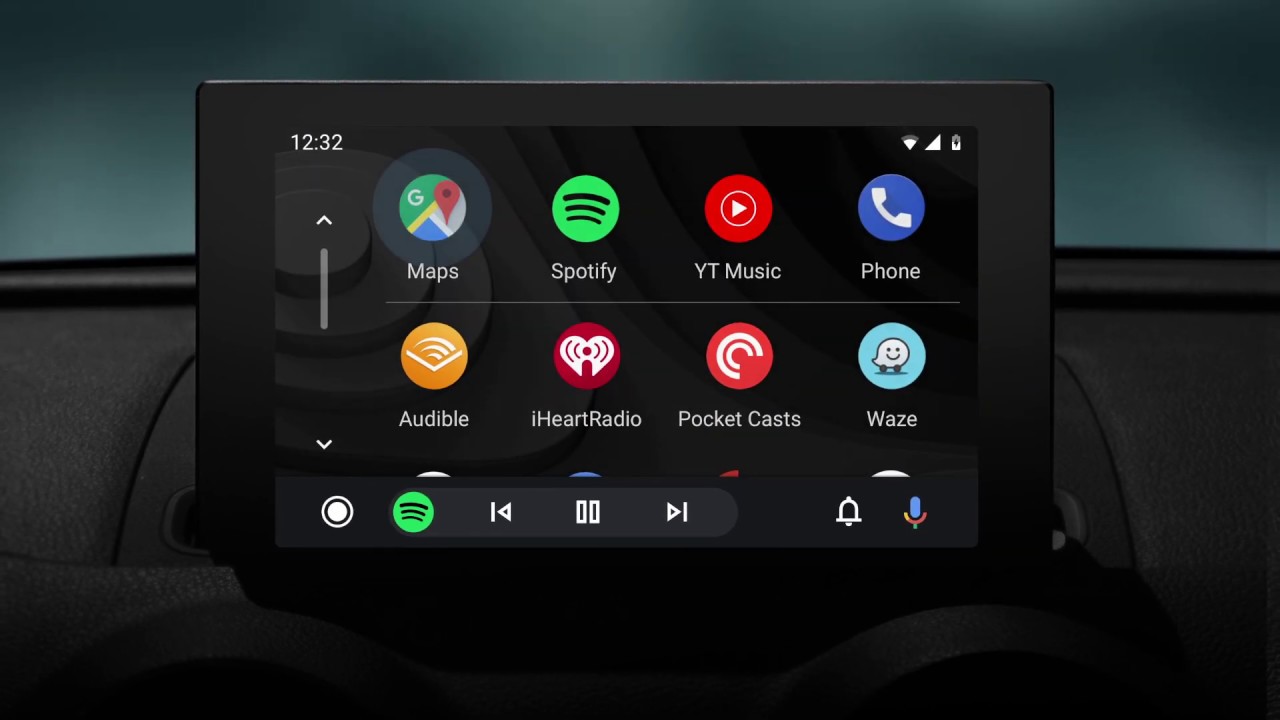

The case is about Android Auto, which is an application that gives access to some of Android’s features on a car’s dashboard. Thus, instead of accessing these features (say, Google Maps) via the smartphone, they can be accessed, more conveniently, via the car’s own display.

Enel’s complaint concerned Google’s refusal to allow one of its applications (JuicePass) to feature on Android Auto. JuicePass provides assistance to drivers of hybrid and electric vehicles: more precisely, the application allows car users to search for charging stations, book charging slots and pay for the electricity.

According to the complaint, Google’s refusal to allow JuicePass into the Android Auto ecosystem amounts to an abuse of a dominant position. The claim raises a number of interesting issues. I will only focus on two of them: whether Android Auto can be said to be indispensable and whether the refusal would result in the elimination of all competition on the adjacent market. These are the two key conditions that are common to Bronner and Magill (and which are notoriously difficult to establish in practice).

Establishing the indispensability in the case would involve showing that it is not possible to compete on an adjacent market without featuring in Android Auto and that there are not any economically viable alternatives to the said application. The elimination of all competition condition, as the law stands, demands evidence of the certainty, or quasi-certainty, of anticompetitive effects absent access.

The reasoning in the decision is interesting in two major respects. First, the adjacent market is never defined by the authority. It identifies a ‘competitive space’ (‘spazio competitivo‘) instead. Second, the interpretation of the indispensability condition is not obvious to square with the definition provided in the case law (in particular IMS Health, which is the most explicit on the point).

This approach, which departs from that followed in Magill and Bronner, seems to mark the comeback of a doctrine of ‘convenient facilities’ (as opposed to essential). If one pays attention to the remedy, on the other hand, it becomes apparent that the decision is unprecedented in another fundamental respect: the duties imposed on Google go beyond an access obligation. These questions are examined in turn.

Indispensability in Enel v Google: towards tailored access to ‘convenient facilities’?

A look at the facts in Enel v Google suggests that access to Android Auto is not indispensable within the meaning of Magill and Bronner. After all, the application (JuicePass) can be readily downloaded and used (and has been readily downloaded and used since it was launched) on smartphones (via both Play and AppStore). Insofar as there are alternatives around Android Auto, a plain reading of the case law would reveal that the indispensability condition is not met.

The Italian authority hints at a different interpretation of the condition. According to the decision, the indispensability element of the test is met because access to JuicePass via smartphone is not comparable to access via Android Auto. This is so, according to the authority, for safety and/or convenience reasons (using JuicePass on the smartphone is said not to be as safe as using the car’s dashboard; and stopping the car to use the application would not be convenient).

It is difficult to square this understanding of the notion of indispensability with Bronner, which makes it explicit that the condition is not met where there are alternatives around an infrastructure, irrespective of whether they are ‘less advantageous’. The decision, in this sense, is indicative of the return of a ‘convenient facilities’ doctrine that would substantially lower the threshold for intervention in refusal to deal cases. Indispensability, under this new approach, means the ability to use apps in an ‘easy and safe way’ (‘in maniera facile e sicura‘).

The passage addressing the remedies suggests that the indispensability condition is also expanded in a different direction: Google has been required to ensure that JuicePass has access on the terms and conditions that Enel deems indispensable. From this perspective, the decision marks a move from an objective understanding of the notion to a subjective interpretation: what is indispensable depends on what each specific firm demands and deems necessary.

Will Bronner and Magill survive common carrier antitrust?

Many disputes in digital markets concern the terms and conditions of access to an input or platform. Therefore, it was only a matter of time before the Bronner and Magill case law would be directly challenged in an outright refusal to deal case: it is not a secret that indispensability is very difficult to establish in practice and thus acts as a limit to how much digital ecosystems can be refashioned by competition authorities.

Given the obvious and substantial tension between the Italian authority’s decision and the relevant case law, there is a chance that the issue is eventually brought before the Court of Justice, which has recently reaffirmed the principles of Bronner and Magill (including the importance of preserving firms’ incentives to invest and innovate) in Slovak Telekom.

It remains to be seen whether the case law, including Magill and Bronner, survives common carrier antitrust. In this regard, it is interesting to note that Enel v Google applies, avant la lettre, some of the concepts underpinning recent legislative proposals (and in particular the notion of gatekeeper). Future law, rather than existing law, appears to drive and shape enforcement. Fascinating times indeed.

As usual, I have nothing to disclose.

Thanks for the post. I read that the AGCM argues that indispensability means the ability to use apps in an ‘easy and safe way’ (‘in maniera facile e sicura’).

Did the AGCM provide this interpretation in explaining what the Court meant by “indispensability” in Bronner and Magill?

WW

28 May 2021 at 9:23 am

You may want to take a look at paras 376-382, where the AGCM advances this interpretation of the indispensability condition and refers to the relevant ECJ case law. Thanks for the comment!

Pablo Ibanez Colomo

28 May 2021 at 10:08 am

Hope a similar development from India may be of interest to you.

Recently, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) has also taken a very similar approach in an interim order passed against a dominant hotel aggregation platform, Make My Trip (MMT). MMT had entered into an exclusive agreement with a hotel franshise called OYO and as a consequence of the exclusive agreement, de-listed OYO’s competitors from its platform. CCI directed that in the interim, MMT must relist the hotel franchises until the investigation is concluded.

The CCI, without really analysing the whether MMT’s platform is ‘indispensable’ in terms of Bronner and Magill, found that the de-listed competitors were suffering due to non-access to MMT’s platform. The fact that the loss of revenues were largely on account of the covid-19 induced lockdowns (and change in customer behaviour) was not considered by the CCI. Most importantly, it failed to appreciate that the de-listed hotel franchises had their own applications that could be downloaded from the App Stores, just like MMT’s applications, so MMT’s infrastructure was really not that essential!

Again, as you mentioned, there seems to be an implied rationale in the order, that these platforms are gatekeepers and require intervention / regulation. However, there is no law as of yet in India on these aspects neither are there any legislative proposals to that effect! Regulating a platform like MMT also seems like an overkill as it is not really BigTech. Competition authorities really seem to be getting ahead of themselves in their overzealousness in the digital market.

Desi Competiiton Lawyer

5 June 2021 at 7:49 am

[…] vom Blog Chilling‘ Competition haben dazu vor einiger Zeit einmal die Kritik geäußert, dass mit diesem Ansatz der Zugang zu einer unerlässlichen Einrichtung zu einem Zugang zu einer bequ…. So hätte in diesem Fall das nachfragende Unternehmen weiterhin die Möglichkeit, außerhalb von […]

Zugang zu Android Auto für alternativen Karten-App-Betreiber - Sebastian Louven

30 August 2021 at 10:01 am

Thhis is awesome

Jimmy

6 October 2021 at 5:36 pm

[…] of the doctrine in digital markets an also marked a tendency of the Authority towards a convenient facility doctrine. This controversial argument regarding alternatives may not be necessary under Section 19a ARC, as […]

Google's Automotive Services under the Scope of Section 19a ARC - Kluwer Competition Law Blog

10 August 2023 at 12:42 pm