The (second) modernisation of Article 102 TFEU: the acquis in the case law and the remaining uncertainties (II)

My paper on the (second) modernisation of Article 102 TFEU (see here) has been out on ssrn for around a week. I am really grateful to those who have already reached out with (their thoughtful and illuminating) comments, and would definitely welcome more.

A significant fraction of the paper is devoted to taking stock on the acquis on the notion of abuse and to identify the areas where some uncertainties remain. I thought the exercise made sense, given that the community is about to embark in a conversation about the codification of the case law.

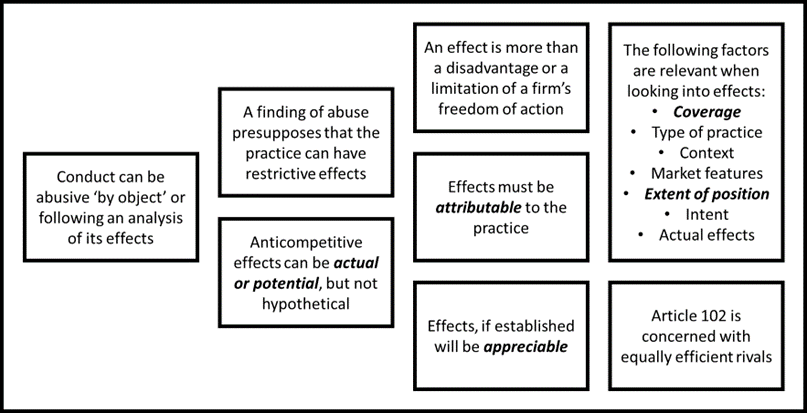

The acquis on the notion of abuse

The picture above, which you will also find in the paper, seeks to capture the contributions made in the long decade that has passed since the 2010 Deutsche Telekom. It easy to underestimate how much the case law has evolved during this period. One can now identify a number of principles guiding the interpretation of the notion of abuse, which are useful both in relation to old and new categories.

If I were to summarise the fundamental contributions made by the Court, I would emphasise the following developments.

First, it is now clear some practices are abusive only where they are a source of anticompetitive effects in the relevant economic and legal context. As a result, an authority or claimant will have to establish foreclosure to the requisite legal standard at least in some instances. This point may seem obvious now, but it was anything but straightforward in the aftermath of British Airways.

Second, anticompetitive effects must be attributable to the practice for Article 102 TFEU to apply. In other words, there must be a causal link between the practice and the actual or potential impact of the strategy.

The corollary of the second development is, third, that Article 102 TFEU is concerned, at least as a matter of principle, with equally efficient rivals. Where the exclusion of a rival is attributable to the fact that the said rival is less efficient and/or less attractive in terms of inter alia, prices, quality or innovation, Article 102 TFEU does not come into play.

The paper discusses two other key functions that the (much misunderstood) ‘as-efficient competitor’ principle has in the system.

This principle is also important from the perspective of legal certainty. As the Court emphasised in Deutsche Telekom, a dominant firm should have the means to assess whether or not its behaviour amounts to an abuse. For instance, one cannot expect a firm to adapt its conduct to the costs structure of a rival (which is the example given by both the GC and the ECJ in Deutsche Telekom).

More generally, the ‘as-efficient competitor’ principle is a valuable reminder that Article 102 TFEU is a device to protect the competitive process, not to engineer market outcomes and/or to decide how many and which firms should operate in the relevant market. The latter task is the natural province of sector-specific regulation, not of competition law.

Third, the Court has defined a number of factors that need to be considered when evaluating the actual or potential impact of a practice on competition. Post Damark II identified factors such as coverage and the extent of the dominant position. In addition, the features of the relevant market (including the regulatory context) played a central role in the assessment in that case (more in this below).

In Servizio Elettrico Nazionale the Court ruled, in line with the Guidance Paper, that evidence of actual effects (or the lack thereof) are to be considered (even if it is not conclusive in and of itself).

The remaining uncertainties

In spite of the abundant clarifications provided by the Court over the past (long) decade, there are, inevitably, some issues that need to be clarified (surprising as it may sound, the case law is still a work-in-progress).

One such issue is the probability threshold that applies when the analysis is prospective (that is, when the assessment concerns potential, as opposed to actual, effects). As I explain in the paper, this question is distinct from the definition of the standard of proof, even though both tend to be conflated very frequently.

The probability threshold is not just an academic diversion: it has major consequences for the definition of the scope of Article 102 TFEU. It is one thing to say that the threshold of potential effects is satisfied when the probability of harm is in the region of 10-15%, and another one to say that the likelihood of harm should be of at least 50% for Article 102 TFEU to apply.

As I discussed in the paper (and in previous pieces), the Court has not defined the probability threshold, but I agree with Advocate General Kokott, for whom the notion of potential effects presupposes a probability of harm of at least 50% (see her Opinion in Post Danmark II). It is the interpretation that best captures, in my view, what the Court has actually done.

A second issue that needs to be clarified relates to the assessment of the counterfactual. I have mentioned in the past that debates around this matter may seem surprising. Establishing a causal link between a practice and its effects demands, by definition, identifying a counterfactual. One could argue, therefore, that the Court has (if only implicitly) addressed this point.

What is more, the Court has already had the chance to clarify that the counterfactual is necessary in the context of Article 101 TFEU. I cannot think of a valid reason why the analytical framework would change depending on the applicable provision (it would amount to attaching different meanings to the same concepts based on whether one or the other is applied).

Third, it is not clear when and why departures from the ‘as-efficient competitor’ principle are deemed justified. In Post Danmark II, the Court ruled that the exclusion of a less efficient rival could be a concern insofar as the legal context made the emergence of an equally efficient one virtually impossible. In such a context, Article 102 TFEU protects the modicum of competition that sector-specific regulation allows. It remains to be seen whether, and why, other departures from the principle are possible

Thanks for doing this Pablo. It is a great resource for all of us.

Best,

Stephen

Stephen Kinsella

20 October 2023 at 11:21 pm