Case T-136/19, Bulgarian Energy Holding (Part I: Substance)

Last Wednesday the General Court annulled the Commission’s abuse of dominance decision and €77 million fine in BEH (Judgment available here). The GC’s Judgment is a rare instance of a full annulment of a Commission abuse of dominance position (prior instances include the 2022 Qualcomm GC judgment, which the Commission did not appeal, the 1979 CJ Hugin judgment, the CJ 1973 Continental Can judgment and the CJ 1975 General Motors judgment).

But beyond anecdotal stuff and case-specific circumstances (a complaint filed by a company that was until 2021 jointly controlled by Gazprom against a public Bulgarian company performing public service obligations in a country dependent on Russian/Gazprom gas during a period in which Gazprom was abusing its dominant position), the reason why this case matters is because of its relevant contribution to the assessment of causality and evidence in abuse of dominance cases.

Remarkably, the GC found that BEH had an exclusionary “modus operandi” for a certain period (see paras 949, 1079, 1083 and 1089), but concluded that the Commission’s decision nevertheless failed in numerous critical respects. The judgment presents a very thorough fact and evidence intensive assessment by a first-instance court.

Here are a few preliminary observations on the substance of the Judgment (skipping the section on market definition and dominance, as well all the various pleas examined in great detail but ultimately rejected by the GC as unfounded or ineffective). Since this is a lengthy and fact-intensive Judgment (I’ve had more entertaining flight reads; at one point I kind of regretted having read the Judgment over the alternative I was carrying…), we will summarize and simplify the debate a bit. We will cover procedural issues in a separate post:

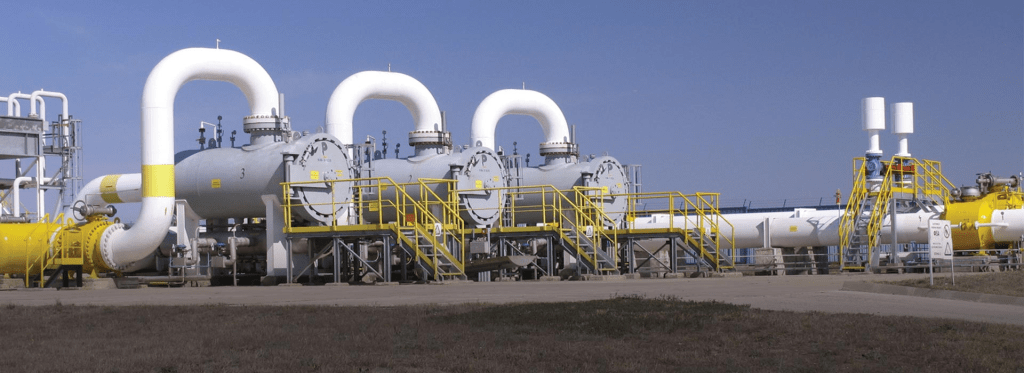

The conduct under examination. The conduct at issue was BEH’s (a vertically integrated state-owned energy company with a license to act as the sole public supplier of gas in Bulgaria) alleged attempt to block competing wholesalers’ access to key gas infrastructure in Bulgaria that it owned and operated (namely the gas transmission network, the only gas storage in Bulgaria, and the only import pipeline bringing gas into Bulgaria, which was fully booked by BEH). The Commission’s Decision found BEH dominant both in the gas infrastructure markets and in the gas supply markets in Bulgaria (a finding upheld by the GC), and concluded that it had engaged in a pattern of behavior aimed at preventing, restricting and delaying access to infrastructure.

Essential facilities doctrine – Bronner is alive (and so am I despite my recent, and not so recent, inactivity on this blog…) .The GC endorses the finding that the pipeline and the storage facilities at issue were essential facilities due to the lack of any alternative (as well as the finding that Bulgargaz was in a dominant position due to its control of the infrastructure even if it was not the owner of the facility). From para. 255 onwards (and in multiple recitals thereafter) the Judgment discusses the application of the Bronner conditions, highlighting the relevance of the indispensability conditions and the fact that the stricter Bronner test is justified because an obligation to conclude a contract “is especially detrimental to the freedom of contract and the right to property of the dominant undertaking” (para. 257, also 258, 282 and 451). The GC takes into account the fact that the facilities in question were built with public resources and the possible existence of a regulatory obligation to deal (e.g. paras 962 and 968-969). This is all fully in line with established case law.

A “refusal” to provide access and the issue of potential competition. One of the Commission’s allegations was that capacity hoarding on the essential pipeline constituted a refusal to supply. The GC finds that in order to prove that BEH’s conduct was liable to eliminate all competition in a neighbouring market on the part of the person requesting the service, there needs to be “proof that the potential competitor has, at the very least, a sufficiently advanced project to enter the market in question within such a period of time as would impose competitive pressure on the operators already present”, as otherwise the alleged effects would be purely hypothetical (para. 281, citing Generics and Lundbeck, also 447-452 which set a higher bar by requiring the Commission to establish rivals’ “firm determination”, “capacity”, “preparatory steps” and “sufficiently tangible project” to enter those markets). The GC concluded that in the case at issue these requirements were not met. In other (AG Kokott’s) words in Generics, there can be no restriction absent potential competition. In other (my) words, the question of whether a given conduct restricts competition needs to be established by reference to the degree of competition that would likely have existed in its absence because otherwise effects would be merely hypothetical. This, in my mind, is very sensible. The question of how far the Commission must go to establish what would have been a realistic/ likely counterfactual is a separate and case specific one.

Interestingly, the GC explains that, because of the serious interference on the freedom to contract derived from obligations to provide access, the dominant company must “be in a position to assess whether it is required to respond to it, failing which it might be exposed to the risk of an abusive refusal of access. However, a purely exploratory approach on the part of a third party to the dominant undertaking controlling access to the infrastructure in question cannot constitute a request for access, to which the dominant undertaking would be required to respond” (para. 282, also 450). The GC finds that the Decision did not show that BEH’s rivals had made a clear request for access to the pipeline to enter the Bulgarian gas supply market, that merely exploratory questions are not sufficient to show a sufficiently advanced intention to enter the market (para. 285, also 459 et seq.), and that requests made to another party (Transgaz) were not communicated to BEH (e.g. paras. 292-294 and 325-333).

Given its position in other cases and the upcoming Article 102 Guidelines, it will be interesting to see whether the Commission agrees with (or can live with) this idea that obligations to supply require an explicit request and an explicit refusal. For background, this is something that arguably does not feature in previous Commission decisions or in the case law, but that did feature in the GC Google Shopping Judgment (note that the President of Chamber and the reporting judge in that case are among the 5 judges signing this case too). I recently explained my view on this question before the Court of Justice, so I will avoid doing that here.

The GC also found that the Decision failed to show unreasonably stalling behaviour by BEH following a detailed analysis of the evidence and of the parties’ written communications which rather revealed a “constructive attitude” (e.g. paras. 359, 364, 395-396 and 442-443).

State action defense and protection of the dominant firm’s interests. Part of the Judgment (paras. 483- 687) is devoted to upholding the argument that some of the relevant conduct was imputable to Bulgaria and Romania negotiation of an agreement in a context characterized by Bulgaria’s dependence on Russian/Gazprom gas (which could only be transported through the controverted pipeline), which also explained BEH’s public service obligations aimed at ensuring security of gas supply in Bulgaria. This context appears to have weighted heavily on the GC, which underlines (i) that the State action defence makes it possible to exempt undertakings from their liability for conduct required by national legislation (paras. 548, 572, 616), and (ii) the legitimacy of dominant firms taking proportionate steps to protect their commercial interests (547, 616, 625). The GC finds that it was legitimate and reasonable for BEH’s subsidiary to take measures to guarantee a minimum capacity reflecting its needs as a public supplier. The GC did not make these findings under an “objective justification” analysis, nor did it examine “less restrictive alternatives”. Query whether the reasoning and outcome on this point would have been the same in a case involving a non-public company or in a situation where dependence on Russian gas were not relevant.

Causality/ Attributability. The assessment of causality /attributability of effects to the impugned conduct is one of the main issues at stake in pending Article 102 cases. It is also one of the topics that the Commission is expected to deal with in future Article 102 Guidelines. The case law requires that anticompetitive effects be attributable to the impugned conduct, and the Commission takes the view that “requiring a nexus of full causality between the conduct and the anticompetitive effects” would “render enforcement unduly burdensome or impossible” (EC Policy Brief, p. 4). In my view, this Judgment is mainly relevant because of its contribution to that debate.

As explained above, in this case the GC finds that an alleged refusal to deal cannot be likely to eliminate all effective competition in a downstream market where there is no evidence that the rivals requested access, or where there is no evidence that they had the firm intention to enter that market. This, in my mind, reflects a clear counterfactual thinking, an approach to causality not unlike the substantive reasoning in the Qualcomm judgment. As also explained above, the GC also found that part of the impugned conduct could be attributable to Member States or derived from BEH’s legitimate protection of its interests in light of its public service mission and obligations (see above).

In addition, and perhaps even more interestingly, the GC explains that even if BEH adopted an anticompetitive modus operandi that hindered rivals’ access to the transmission network and storage facilities and failed to comply with its regulatory obligations during a certain period (paras. 949-950, 953 and 1089-1100), this was incapable of restricting competition. This is because rivals lacked access to the only pipeline available to transport gas from Russia into those facilities “for reasons which are not attributable to proven abusive conduct” (para. 951; in my view, likely to be the most quoted paragraph of the Judgment in the future). In other words, the GC concludes that there is no restriction of competition (para. 953-954) because absent the impugned practices rivals would not have been able to compete anyway.

Another (Article 101) Commission decision in the same sector was already annulled on similar grounds (absence of potential competition) in EON/Ruhrgas. The peculiar regulatory framework applicable in these markets arguably makes things more complex for the Commission but, for that very reason, it contributes to triggering corrections and results in lessons that might be relevant across the board.

To be continued…

“The GC’s Judgment is a rare instance of a full annulment of a Commission abuse of dominance position (the 2022 Qualcomm GC judgment, which the Commission did not appeal, the 1979 CJ Hugin judgment, and the CJ 1973 Continental Can judgment being the only other examples).”

Apologies for the pedantry, but Case C-26/75 General Motors Continental NV is also an example

Spaniel

1 November 2023 at 12:39 pm

No need to apologize, particularly when you’re right. Editing the post accordingly. Thanks!

Alfonso Lamadrid

2 November 2023 at 11:12 am

Welcome back! Everyone was wondering…

This is a complex judgment, that requires more than one reading to properly understand it, in my view. I understand your temptation to read into the judgment something about causation, but I have the impression that this is mixing issues of (lack of) potential competition, proof and attributability of the conduct, and causation. First, the expression causation or causal link is nowhere to be seen in the judgment. Second, the judgment does refer to “attributabity” in some paragraphs but more often to point out that the lack (or delay) of access was not attributable to the dominant undertaking, in particular because there was no request for access, because it was not the dominant company who denied access, or because delays in access were not unjustified or were not attributable to the dominant undertaking. Logically, if an infringement is found to consist in denying or unduly delaying access (or entry), one must examine whether the dominant undertaking actually did that. This is about proof of conduct and its attributability to the undertaking.

Paragraph 951 cross-refers to 291-293 and 325-33 which discuss whether there was any denial of access to the pipeline by the applicants (and the GC concludes that the applicants did not deny access, i.e. lack of access to pipeline was not attributable to applicants, but to someone/something else). They do not discuss causality. The point in 951 appears to be that the conduct regarding the transmission network could not ultimately restrict competition since there was no potential competition to be restricted in the first place (also applying Generics and Lundbeck earlier in the judgment) since the operator in question did not (and could not) have access to the pipeline (so effects were too hypothetical). That ground appears to be conceptually different from lack of causation between the (proven) conduct and the effects (unless one sees a discussion on causation in every case where the lack of potential competition is discussed). I fail to see any similarity with other “pending cases”, but probably you have more info on pending cases. This does not mean some lawyers may not try to rely on paragraph 951 in the future, though, to the extent that they do not find anything else supporting their case on causation in any other judgment so far.

Pedro

3 November 2023 at 9:47 am

This blog post provides a detailed analysis of the General Court’s annulment of the European Commission’s abuse of dominance decision and fine in the Bulgarian Energy Holding (BEH) case. The author highlights the case’s significance in contributing to the assessment of causality and evidence in abuse of dominance cases. Key points include the essential facilities doctrine, the issue of potential competition, state action defense, and causality/attributability. The blog suggests that the court’s clear counterfactual thinking and examination of causality make the judgment noteworthy in ongoing Article 102 cases. Additionally, the post mentions that a Court Reporter covered the case in detail.

Court Reporter

28 December 2023 at 11:11 am

This is a great comment. Quality of comments increasing every week.

Tar

2 January 2024 at 12:00 am