Archive for the ‘Antitrust Scholarship’ Category

Bork on Private Enforcement

A refreshing – and couterintuitive – quote from Judge Bork as the EU is heading towards increased private enforcement:

“Much of the improvement in antitrust policy over the past decade and a half has come not from the courts but from the enforcement agencies. If the courts abandon economic rigor, only those agencies can preserve the rationality of the law, and then only partially. Private plaintiffs and their lawyers have rather less interest in rational rules than they do in triple damages and contingency fees. Expert economic witnesses can be found to support any theory. Without firm judicial control, private actions make antitrust “policy” ad hoc, as trials become ad hominem. Much more could be said about the devastating unfairness and anticompetitive consequences of much private antitrust litigation, but that is outside the scope of this book. In antitrust, it is possible to think the European Community as has wisely not followed the american example but has instead centralized all enforcement in a single government agency” (The Antitrust Paradox, Epilogue p.439).

In brief, Bork accuses the US courts system of the state of theoretical confusion in which antitrust law was until the 1980s. And he says that agencies often promote better substantive standards (though they select those most advantageous to them) than courts who hear cases brought randomly by private parties with evolving business interests.

We surely can agree with Bork – as we have endlessly advocated on this blog – that with prospects of increased private enforcement in the EU it becomes compelling to (i) induce judges to delve more into economic analysis; (ii) require a very stringent system of judicial review.

Sunshine lawyering

Being a competition lawyer one cannot help but to be interested in the competitive dynamics of the very market in which we operate.

There are a few odd things to it, but I usually -although not on this blog- refer to one particular market failure in the market for EU competition law legal services: its lack of transparency (not price wise, but rather quality wise). My take on this (developed below) is that making certain legal submissions public would contribute to addressing this market failure. The report on accesibility of Court documents just issued by the European Parliament has given me an excuse not to comment on the Google commitments that I’ve been unable to read in full the push I needed to write about it.

It’s funny to observe that the cult of personality/firms prevalent in the EU competition world is, to a great extent, grounded on practically no available information. Firms and individuals are revered and ranked in various ways and tiers; they (we) are reviewed, reveive prices, etc, but, if you stop for a sec to think about it: how do you know that any of them/us is any good?

The maximum information that one can get about the quality of a firm’s or lawyer’s work merely relates to the cases in which a given firm/lawyers has worked. Interestingly, the outcome of those cases tends to matter little; what appears to matter is to have been involved in them. Many lawyers advertise the fact that they have acted on particular cases regardless of the result, and there’s no way of knowing whether they did excellent, good enough or poorly (at the extreme, I know a few cases of lawyers who show off for having represented clients in proceedings initiated as a result of poor legal advice in the first place). To be sure, although outcomes are, at times, a very good proxy, they are not a definitive criterion, for we often know little about the objectives pursued, about the details of a case, or about its a priori odds. Actually, telling whether an outcome is positive or not, as well as determining what a lawyer’s/economists’ contribution to this result was, is almost always unfeasible.

I’d argue that the only ones who can really have an informed idea about how good a firm or a lawyer is are the people working at the Commission and at the Courts who have shared cases with them/us; they are the sole ones who are able to measure their/our work against the background of all factors in play (when it comes to pleading, the Mlex guys who listen in at the hearings could have something to say too; I’ve said before that Lewis Crofts could make some extra money by publishing a litigators’ ranking..) but no one asks them (and even if they were asked, it’s arguable whether they should disclose favoritism in this regard either).

You could argue that in-house lawyers can be good comparative judges as well, but this is not always the case: in-house lawyers are often exposed to a very reduced subset of lawyers (sometimes retained due to political reasons outside their control). Moreover, many in-house lawyers may not be experts in the area for which they hire external lawyers (this is frequent in the competition world except when you deal with particularly large firms with specialized competition counsel), and very often the less risky thing to do is to pick people who others perceive as triple A, even if the reasons justifying the perception are ranking based unknown (the force of inertia and virtuous/vicious circles do the rest).

I’ve worked in various cases where I’ve seen well-known lawyers and firms produce documents that were not…worthy. I’ve also seen well regarded firms (sometimes even the sames as in my previous example) produce excellent work. And I’ve also seen work by less-known firms that was pretty good. The interesting thing is that in these cases the quality of the work tends to impact the result ot the case, but not the firm’s/lawyer’s reputation, for good or for bad, because no one can see and assess what was done.

In sum, to a great extent, law firms and economic consultancies are credence goods.

If you ask me, the only way to get rid of many of the absurdities derived from this market failure, and to improve the quality of legal services at the same time, would be to increase the transparency of legal submisions. It has happened all too often that I read something (a document, a plea or an argument) and wonder whether it would have been billed for written had its authors known that it would be publicly available.

Nico and Miguel Rato wrote a few years ago about sunshine regulation; I would argue that sunshine lawyering would also be a good thing; why not follow the example of the U.S., where Court filings are considered to be public records? There are very good reasons why this should not be the case in administrative proceedings, but I see no impediment in the case of Court proceedings, and nor does the European Parliament’s report recommending that changes be adopted in order to facilitate access to Court files at the EU level.

Commission bashing (part II)

A few days ago Nico wrote a post about “Commission bashing” in which he acknowledged that, in reality, he’s not a Commission basher but rather appreciates the good things that Comp does [the fact that one of the three examples given -next to the Guidance Paper and the effects-based approach..- was Post Danmark -a Court Judgment- reveals that Nico struggled to find good deeds on the Commission’s part :)]

Until now, the most vocal Commission basher I knew of was Michael O’Leary, Ryanair’s CEO (check out his CV and the accompanying Commission disclaimer here.) We’ve previously referred to his comparison of Comp officials with Kim Il-Jung (sic) and with North Korean economists, but you may not have watched his equally… outspoken intervention at the EU Innovation Convention in 2011 (worth checking it out here)

But Mr. O’Leary now faces fierce competition. A blog called Venitism appears to overpass Ryanair’s chief’s tone; it has just published a post mildly titled: The stupid European Commission harassess the chip industry. Actually, the title is much softer than its content and than its pics. It’s so overdone that it’s worth taking a cursory look if you’ve a minute.

Aside from insulting the Commission, the post states that its authors have conducted a survey that reveals that 80% of economists would favor the abolition of antitrust rules. I’m told by my economist friends that this cannot be true, for, they say “the literature makes it clear that antitrust law promotes our welfare” 😉

Private Enforcement in Ireland

Hart has offered us a book in exchange of some advertisement on this blog.

So here we go: their latest competition law volume is a book by David McFadden entitled “The Private Enforcement of Competition Law in Ireland”.

Abstract: Competition is recognised as a key driver of growth and innovation. Competition ensures that businesses continually improve their goods and services whilst striving to reduce their costs. Anti-competitive conduct by businesses, such as price-fixing, causes harm to the economy, to other businesses and to consumers. It is small businesses and the consumer who ultimately pay the price for anti-competitive conduct. A coherent competition policy that is both effectively implemented and effectively enforced is essential in driving growth and innovation in a market economy. The importance of competition was recently emphasised when the EU/ECB/IMF ‘Troika’ included a number of competition specific conditions to the terms of Ireland’s bailout. Both Irish and Community law recognise the right for parties injured by anti-competitive conduct to sue for damages. This right to damages, in theory allows those that have suffered loss to recover that loss whilst helping to deter others from taking the illegal route to commercial success. However private actions for damages in Ireland are rare.

This book asks what the purpose of private competition litigation is and questions why there has been a dearth of this litigation in Ireland. The author makes a number of suggestions for reform of the law to enable and encourage private competition litigation. The author takes as his starting point the European Commission’s initiative on damages actions for breach of the EC antitrust rules and compares the position in Ireland to that currently found in the UK and US.

David McFadden is Legal Adviser and solicitor to the Irish Competition Authority and has published extensively on competition law and other regulatory issues in Ireland.

April 2013 302pp Hbk 9781849464130 RSP: £50 / €65 / US$100 / CDN $80

20% DISCOUNT PRICE: £40 / €65 / US$80 / CDN$80

Order Online in US

USA: http://www.hartpublishingusa.com/books/details.asp?ISBN=9781849464130

If you would like to place an order you can do so through the Hart Publishing website (link above). To receive the discount please type the reference ‘CCB’ in the special instructions field. Please note that the discount will not show up on your order confirmation but will be applied when your order is processed.

Order Online in the UK, EU and Rest of World

UK, EU and ROW: http://www.hartpub.co.uk/BookDetails.aspx?ISBN=9781849464130

If you would like to place an order you can do so through the Hart Publishing website (link above). To receive the discount please type the reference ‘CCB’ in the voucher code field and click ‘apply’.

Hart Publishing Ltd, 16C Worcester Place, Oxford, OX1 2JW

Telephone Number: 01865 517 530

Fax Number: 01865 510 710

Website: http://www.hartpub.co.uk

Auto-critique + Mixed bag of thoughts

I’ll tell you a secret. I’ve lately been quite frustrated with regard to my latest contribution to this blog. In the past few weeks there have been very interesting substantive developments that we could’ve covered, but I’m having increasing trouble to find the time to write here. That’s a problem, for it makes little sense to write for a (now) large audience unless you’ve something meaningful to say. So I thought, either I quit, either I make an enhanced effort to post some -arguably decently- interesting stuff. Risking sleep deprivation I’ve chosen option 2.

But, as with all important commitments, I’ll start next week 🙂 For the time being, I’ll leave you with some brief thoughts on some of the different issues that we’d like to cover more in depth in posts to come:

1) On Google’s proposed commitments: Some basic elements of Google’s proposed commitments were leaked to the press (see the Financial Times’ piece on this). Rumor has it that the text to be market tested next week will be a bit dense, which has given us an idea for our very own commitment: we commit to explaining its content as objectively as we can in order to make Chillin’Competition a forum of discussion on this topic.

Some preliminary comments: (i) DG Comp appears not to object to Universal search itself; the basic description of the commitments reveals that the Commission has sensibly engaged in a balancing exercise which aims at creating more room for competition without disrupting too severely Google’s successful and innovative business model; (ii) apparently the commitments in relation to search mainly concern changes in Google’s user interface (UI). I would be curious to know who within COMP took responsibility for assessing what changes needed to be effected on something as important to Google as their UI (some say that the Commissioner himself had a significant intervention on this point!). We’ll come back to this as soon as there’s more info available.

2) On the reactions of Google’s complainants to the commitments: A few weeks ago –while teaching a 6 hour course on procedure at the BSC in the middle of easter (my gf appreciated that we had to break our holidays for this…) I had to talk about, among others, commitment decisions and I used the Google case to illustrate some points. I realized then that many people don’t know that when the Commission adopts an Art. 9 decision in a case in which it has received complaints, it also has to adopt specific decisions rejecting each complaint. Now, if complainants were really sure that their theory of harm fits within current legal standards and that the commitments are insufficient, they would appeal the decisions rejecting the complaints, right? I’m not sure they will (even if it would be interesting to read for once how this case can be framed in legal terms).

Also, some complainants are there to address a specific business concern that they have concerning Google’s practices; others seem to be there just to put some sticks on Google’s wheels no matter what. I’m intrigued as to whether these two categories of interested parties will adopt the same approach from now onwards or not…

3) On Nico’s yesterday post on the Expedia Judgment: Readers of this blog will not be surprised at the fact that Nico and I disagree on something 😉 I told him yesterday that I didn’t share his reading of the Expedia Judgment. In fact, when it came out I thought about writing a post on it, but when I read it I thought it was so common-sensical that there was little to be said.

However, and whereas I still like the overall Judgment, I now get Nico’s point, and I understand that para. 37 of the Judgment might sound equivocal. I also see the point in the comments made by Bagnole and Asimo to that post. My take on it: the criterion of “appreciability” of restrictions of competition has a qualitative and quantitative dimension; restrictions by object are qualitative appreciable by definition; the quantitative appreciability criterion should be assessed separately. In this case the Court appears to assume that, to the extent that trade between Member States is affected the quantitative requirement is fulfilled, which could be understandable, but it’s also very arguable. Effects on inter-State trade may be an acceptable proxy as Bagnole and Asimo say, but I’d rather regard this as a different jurisdictional element not necessarily related to the quantitative significance of the restriction. True that in practice the Völk Judgment mixes them, and true that Expedia does too, but strictly speaking they’re different things.

(I hope this is clear despite the abstraction; I’m writing while on a plane next to someone who’s snoring [(-_-)zzz] and trying that my diet coke doesn’t spill on me, so I’ve trouble concentrating…)

Pay also attention to the fact that para 11 of the de minimis notice solely states that the threshold in the Notice are not applicable to hardcore restrictions, but it does not exclude the possibility that a hardcore restriction could be considered of minor importance when the combined market power of the parties is significantly below those thresholds.

4) On the CISAC Judgments: Last Friday the General Court issued its Judgments in the Cisac case. We haven’t commented on them because the case is quite complex, and having only skimmed through it I would risk saying some stupidity missing something. We’ll come back to it. A couple of non-substantive interesting things in the meanwhile: (i) There have been various outcomes to the case for different parties: some did not appeal –apparently because they liked the new scenario-; others (the Spanish applicant) missed the deadline to lodge the appeal (I’ve nightmares about this ever happening to me), and others appealed everything but the point on concerted practices, which is the one that has been quashed. At the end of the day, however, the result may matter little in practical terms, for collecting societies could always unilaterally decide to do adopt any licensing policy, including the same one challenged by the decision (only on the grounds that it had been collectively agreed upon). In any case, I’m told that market circumstances may have changed, and that some collecting societies are now interested in the “liberalization” (in terms of multi-territorial licenses) that the decision sought to promote. (ii) It’s funny to read the Court saying that the Commission failed to explain some stuff; these cases required more than 100 hours of hearings (as our readers may know, the hearings had to be repeated for procedural reasons); Fernando Castillo, the lead Commission agent in the series, is well known for speaking extremely fast; surely he must have explained quite a few things in the course of so many hours !

5) Remember the debate on exhaustion of copyrights in the case of computer programs and the most interesting Usedsoft/Oracle Judgment? The Spanish Competition Commission just issued a decision concerning Microsoft’s policies in this regard. It’s not yet published, but we’ll give you our views on it as soon as it is. [If you prefer not to wait for the free comments that we’ll publish here, I can always offer a premium version at hourly rates 😉 ]

6) More on Microsoft. Some of you may have read that Microsoft is the target of a complaint lodged by Spanish users of Linux. I have no knowledge of this case other than what has appeared on the press (which sounds a bit odd, since it was reported that the complaint was lodged at the Commission’s delegation in Madrid and that it refers to Arts 81 and 82…). Reports say that the complaint alleges that the secure boot system in Windows 8 forces developers to conform to Microsoft’s requirements, thus extending the latter’s dominance in the OS market. Apparently, the new firmware supports authentication with digital certificates of the installed OS and their loader; in order for OEMs to get a “Designed for Windows 8″ label they must comply with Microsoft’s requirements, among which is the one (applicable to ARM equipment) of only booting Microsoft-certified software. Whereas I can’t comment on whether there’s any actual legal basis for this complaint, I’ve come across an interesting technical piece that explains what’s the factual background thereto: see Arstechnica’s piece here.

Law Firms = Cartels

From Judge Bork himself:

“The typical law partnership provides perhaps the most familiar example [of agreement on prices and markets]. A law firm is composed of lawyers who could compete with one another, but who have instead eliminated rivalry and integrated their activities in the interest of more effective operation. Not only are partners and associates frequently forbidden to take legal business on their own …, but the law firm operates on the basis of both price-fixing and market-division agreements. The partners agree upon the fees to be charged for each member’s and associate’s servicse (which is price fixing) and usually operate on a tacit, if not explicit, understanding about fields of specialization and primary responsibility for particular clients (both of which are instances of market division)” The Antitrust Paradox, 1978, p.265.

Bork used this example to criticize the blanket per se prohibition of price-fixing and market division schemes. Cartels formed amongst lawyers yield redeeming efficiencies (the combination of complementary skills, notably) + there are many law firms and all compete fiercely. Hence, output restriction is not a tenable hypothesis.

This later point ties in well with C‑226/11 Expedia Inc. v. Autorité de la concurrence, a judgment poised to earn a “worst antitrust development Oscar”. Bork’s example casts a bright light on the judgment non-sense: in this case, the Court held at §37 that conduct with marginal market coverage (<10%) ought to be deemed to have appreciable anticompetitive effects as long as it can be categorized as a restriction by object:

“It must therefore be held that an agreement that may affect trade between Member States and that has an anti-competitive object constitutes, by its nature and independently of any concrete effect that it may have, an appreciable restriction on competition“

In other words, a price-fixing scheme that covers 5% of the market is per se illegal under Article 101(1) TFEU. Again, a dispairing judgment…

Speaking slots for sale

.jpg)

I landed in Brussels this morning at 7 am after an intense week of cocktails antitrust events at the ABA’s antitrust spring meeting in DC. I’m knackered (I also have to recover from the sight of 2,700 antitrust lawyers under the same roof) and have lots of catching up to do, so let’s keep it simple today:

Nicolas’ Friday post criticized several pricing practices in the conference market, namely excessive pricing and lack of pricing discrimination in favor of academics and students.

This is not a new topic; some of you might remember that many posts ago I proposed an algorithm for competition conferences, positing that “the likelihood of getting to listen to new and interesting stuff is inversely proportional to the combination of three cumulative variables: the price of the event, the number of attendees, and the number and lenght of slide decks. It’s generally not a good sign if an event is pricy and crowded. The ones with a greater chance of not being interesting at all are those for which you have to pay in order to be a spayeaker (yes, there are plenty of those!)”.

I discussed Nico’s post with a few sensible people over the w-e, and the discussion quickly came down to one sole issue: the ‘funny’ (not as in haha, but as in questionable) but prevalent practice of paying for speaking slots, which I had only touched upon in passing in my previous post.

I would argue that paying to speak is essentially a marketing trick based on misleading the audience. Let me prove my point: how many spaykers do you think would want to appear at a conference if the audience had transparent information about who’s paying for the slot and who’s not?

If you’ve something interesting to say, you should get paid for it (not so difficult, even Sarah Palin gets paid to speak) or at least be invited to speak for free. Note also that people who pay to speak would not normally (there are of course exceptions) give objective overviews of the topic at issue; their presentation would tend to be a more or less obvious sales pitch. I’ve nothing against lawyers advertising themselves, but, as in other contexts (some might think of search engines), it’s generally good to be able to tell what’s advertising and what’s not.

The most obvious way to address this “market failure” and push for a merit-based allocation of speaking slots would be to have lawyers stop paying (smart, uh?), but since self-regulation is unlikely to work, I would suggest, for a start, that public officials refuse to appear in conferences where people pay just to sit with them.

What’s your take?

ECJ’s ruling on France Telecom’s State aid case (Joined Cases C-399/10 P and C-401/10 P)

Note by Alfonso: As some you may have noticed, I’ve taken an unusually long blogging break from which I’m now back. As every time I’m out of combat, Pablo Ibañez Colomo (who, by the way, has recently been fast-track tenured -major review- at LSE and has just received a major review teaching prize; congrats!) comes up with a replacement post that’s better of what I would’ve written (we have a luxury bench at Chilin’Competition…). A few days ago Pablo sent us this post on France Telecom that we(I)’ve been slow to publish due to the easter holidaus and to to the frenchy’s posting frenzy 😉 We leave you with Pablo:

Some readers wll remember that during my short-lived tenure as a substitute blogger a few months ago, I wrote about a pending State aid case involving France Telecom. I guess that at least a fraction on those readers will be interested in knowing that the Court of Justice delivered its Judgment in the case on 19 March.

Unsurprisingly, the judgment is in line with AG Mengozzi’s (very sensible) opinion. The General court annuled the Commission’s decision on grounds that the Commission had not identified a clear link between the advantage deriving from a shareholder loan offer in favour of France Telecom and the State resources allegedly involved by virtue of the measure. As I argued in my previous post, the Court of Justice takes the view that the General Court’s interpretation of Article 107(1) TFEU would leave outside the scope of the provision measures suh as guarantees departing from market conditions (see paras 107-111). Such measures do not immediately place a burden on the budget of the State, but a ‘sufficiently concrete risk of imposing an additional burden on the State in the future‘. According to the Court, it is sufficient to identfy such a ‘sufficiently concrete risk‘ for State aid rules to come into play.

The broader picture is aguably more interesting than the outcome of this case. As I mentioned in the previous post, the Court of Justice has sided with the Commmission (thereby departing from the analysis of the General Court and the theses advanced y Mmember States) in some key cases revolving around the notion of selectivity. France Telecom, arguably the single most important case of the past years on the notion of State resources, seems to confirm this trend. The old principles of Article 107(1) TFEU case law, if anything, seem more solid following these high-profile disputes

The Shadow Procedure Rises

Today, Prof. I. Govaere kindly invited me to give a Jean Monnet lecture at the University of Ghent.

The subject was “Public and Private Enforcement of EU Competition Law”. My slides can be found below.

The main point of my presentation was the following: a textual reading of Regulation 1/2003 suggests the existence of a single procedural framework for competition enforcement.

However, my impression is that altogether, several recent legal innovations are giving rise to a “shadow enforcement procedure“.

Under this procedure, the Commission can achieve more in terms of remedial outcomes, with less in terms of evidence.

And if, up to this point, the Commission has (wisely) not yet exploited the full potential of this procedure, it may one day be able to extort even more intrusive remedies from parties without ever having to prove an infringement of Article 101 and/or 102 TFEU. A bleak prediction indeed.

I just wish I have the time to write a full-blown paper on this.

Lecture Gent – 29 March 2013 – Public and Private Enforcement of Competition Law (N Petit)

Lost in Translation

[Please read this post with caution] Heard from a seasoned German-speaking Member of the Court of justice of the EU.

The fuzz about the object-effect dichotomy that has kept generations of EU competition lawyers busy would be a moot issue. We dumd: last year, at the GCLC, we devoted a full conference and book to this issue.

This is because this distinction arguably does not exist [following Hans, Petra and Rainer’s clarifications, I suspect this eminent person meant is “not really relevant”] in the German-language version of the Treaties. Hence the Court’s reluctance to consider effects in antitrust cases.

Puzzled by this assertion, I ran my investigation. At this juncture, I must mention that I am a complete German illiterate.

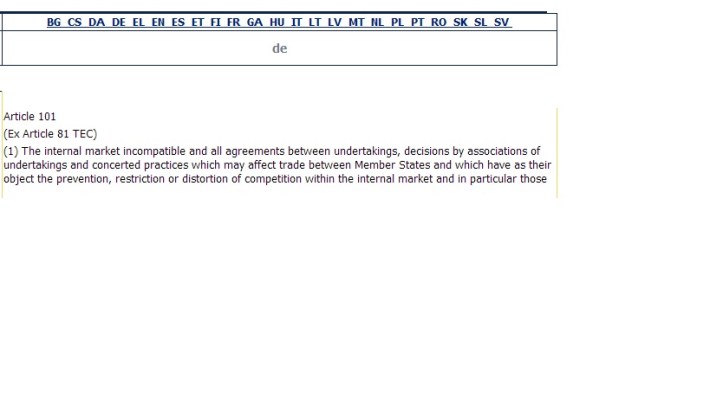

So here we go: I first consulted the wording of Article 101(1) of the Treaty in German:

“(1) Mit dem Binnenmarkt unvereinbar und verboten sind alle Vereinbarungen zwischen Unternehmen, Beschlüsse von Unternehmensvereinigungen und aufeinander abgestimmte Verhaltensweisen, welche den Handel zwischen Mitgliedstaaten zu beeinträchtigen geeignet sind und eine Verhinderung, Einschränkung oder Verfälschung des Wettbewerbs innerhalb des Binnenmarkts bezwecken oder bewirken, insbesondere”

Then I asked Google to translate this text to English:

“(1) The internal market incompatible and all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market and in particular those”

No trace of the word “effect“.

I did the same in French:

“(1) Le marché intérieur incompatibles et interdits tous accords entre entreprises, toutes décisions d’associations d’entreprises et toutes pratiques concertées qui sont susceptibles d’affecter le commerce entre États membres et qui ont pour objet d’empêcher, restreindre ou de fausser la concurrence au sein du marché intérieur et en particulier ceux”

Again, no trace of the word “effect“.

A weird finding. All the more so given that the official Treaty translation explicitly talks of “effect“.

So here I am, pondering whether I am making this up or if, as this distinguished Court Member hinted, there is a linguistic reason for the absence of serious effects analysis in the Court’s case-law.

Now, if the other language versions of the Treaty talk of “effect“, which version of the Treaty is the right one?

Gee, me completely lost in translation.

PS1: On this, I’d advise Google to manipulate its translation service, and reintroduce the “effect” word in all Treaty translations.

See below for more evidence (a print of my screen).