Archive for the ‘Antitrust Scholarship’ Category

More on antitrust and politics: Interview with CPI

As some of you may remember, a few months ago I wrote a post here on “Antitrust and Political Stupidity“. Competition Policy International asked me to develop the post for a special issue of the Antitrust Chronicle, which I did one-handedly during my extended Christmas break (the paper is available here). I was then asked to do a follow-up interview with CPI; the interview was published today (click here for the version in CPI’s web).

Asked about whether I was being too optmistic in the paper, I started my response saying that “my paper was written during the Christmas break, and it is not much more than a Christmas tale, a superficial exercise of wishful thinking” (see below for the complete answer). Little did I know that the mailing that was sent today to some thousands of people would summarize the interview saying that: “Lamadrid says his paper is ‘a superficial exercise of wishful thinking,’ and he tells CPI why“. So, here I am, promoting my work by saying that it’s really not any good (between us: it’s not a masterpice, but it’s somehow original and maybe not as crappy as my own quote suggests…). Man do I really need to work on my self-selling skills…. 😉

If anyone’s interested, you can click here to read the full interview:

Post Danmark – More than just One Case

Our friend Christian Bergqvist has offered us a most interesting post on the national sequel of the CJEU judgment in Post Danmark. Christian is an associated professor at the University of Copenhagen/Faculty of Law. He holds a PhD in competition law and has specialized in particular on dominant firm conduct and the interplay of Article 102 TFEU and sector specific regulation. For more, see here.

PS: for a good reminder of the ruling and of its implications for future competition policy, I advise the reading of the excellent piece of E. Rousseva and M. Marquis (which suggests (in my view rightly) that the Court eventually embraced the Commission’s approach set forth in the Guidance paper).

About a week ago, on Friday 15 February, the Danish Supreme Court delivered its ruling in Post Danmark vs Konkurrenceraadet. This judgment settles the national case behind the (fabulous) 2012 CJEU ruling Post Danmark (C-209/10). Given the strong pronouncements made by the CJEU it does not come as a surprise that the Danish Supreme Court eventually decided to quash the challenged (national) decision on grounds of an incorrect material test. Rather than concluding that discriminatory conduct was per se able to exclude a competitor, the Danish Competition and Consumer Authority, should have conducted an “equally efficient competitor test”, or something close (the latter being my interpretation). Absent this, nothing conclusive could be decided on the existence of an abuse.

The ruling of the Supreme Court leaves little space for ambiguity. Yet, the final word might not have been said on the matter. First, the Danish Competition and Consumer Authority can at least theoretically reopen the case and conduct a proper analysis. This, however, looks quite unlikely. Second, back in 2009, the alleged “victim” of the exclusionary behavior (Forbruger-Kontakt) had successfully filed an action for damages, and was subsequentely awarded DKK 75 million (app. EUR 10 million). Unsurprisingly, Post Danmark has appealed this decision to the Danish Supreme Court, which is yet to decide on the matter.

This short post seeks to offer some thoughts on this issue. Prior to this, I provide some background information on the initial EU case.

Data protection and antitrust law

Regretably I couldn’t attend Concurrence’s New Frontiers of Antitrust conference held last Friday in Paris in spite of Nicolas Charbit’s kind invitation. I hear that the conference was once again most interesting, so congrats again to Nicolas and the rest of the team at Concurrences.

Perhaps the most prominent topic in this year’s program related to the interface between data protection and antitrust law. I’m sorry to have missed the discussions over this issue, for perhaps they would have enabled me to see where’s the substantive beef that justifies all the recent noise. Whereas I understand the practical reasons why this issue has conveniently become a hot one in certain academic circles, I confess my inability to see the specific features that make this debate so deserving of special attention.

The way I see it, personal data are increasingly a necessary input to provide certain online services, notably in two-sided markets. So far so good. But this means that personal data are an input, like any other one in any other industry, with the only additional element that the recompilationa and use of such input is subject to an ad hoc legal regime -data protection rules-.

In my view, competition rules apply to the acquisition and use of personal data exactly in the same way that they apply to any other input, and then there’s a specific layer of protection. I therefore understand that data protection experts have an interest in finding out about the basics of antitrust law to realize about how it may affect their discipline, but I fail to see the reasons why competition law experts and academics should devote their time to an issue which, in my personal view, raises no particularly significant challenges. [The only specificity may be that data protection practices may constitute a relevant non-priceparameter of competition, for companies may compete on how they protect consumer data]. I would argue that this is a serious matter, but one for consumer protection laws to deal with, and in which competition policy may at most play a marginal role (I understand this was also the view expressed by Commissioner Almunia in a recent speech).

To compensate for my absence at Concurrence’s conference, on Saturday morning I read some interesting “preliminary thoughts” published last week by Damien Geradin and Monika Kuschewsky: Competition Law and Personal Data: Preliminary Thoughts on a Complex Issue. The piece provides a contrarian view to the one I just expressed. Since I might very well be wrong (that’s at least what my girlfriend’s default assumption in practically all situations…) I would suggest that you take the time to read it in order to make up your own mind. It won’t take you long, but since behavioral economics (and the clickthrough rates to the links we show) tells us that many of you are of the lazy type, in the interest of a balanced debate here’s a brief account of its content; my comments appear in brackets:

(Click here if you’re interested in reading more)

Competition Policy and Happiness

Many of you have probably had a chance to read various texts on the goals of competition law (the one in Giorgio Monti’s book is particularly good; more recently, I also liked Kevin Coates’ approach).

For an original approach to this discussion, check out Maurice Stucke’s recent paper “Should Competition Policy Promote Happiness?” As noted in the abstract, the paper builds on recent academic literature on happiness and goes on to argue that “competition policy in a post-industrial wealthy country would get more bang (in terms of increased well-being) in promoting economic, social and democratic values, rather than simply promoting a narrowly-defined consumer welfare objective“,

Many thanks to Wouter Wils for the pointer!

P.S. And speaking of papers, Pablo Ibañez, Hans Zenger and myself could use some additional votes for Concurrence’s Antitrust Writing Awards 😉

What I really meant (on recourse to commitment decisions)

As I was exiting a plane on Friday night I received a bunch of email notifications about the comments that were being written to one of our posts (probably the most interesting public discussion over allegations of “scraping” so far; not the post, but the comments to it) in which “Bagnol” made a couple of attempts to clarify what it was that I really meant on my post and in a later comment thereto. At the same time, I read a post written by Nico that started with an idea that I must have thrown out at a conference on why the Commission resorts to commitment decisions, but with which I don’t feel identified (most likely it’s my fault for not having expressed it well). Funnily enough, I couldn’t write any comments on what I really thought because I had committed to take a break from my blackberry (like certain companies I also break my commitments: I had to check my email hidden in an airport’s restroom; yeah, it was very glamorous..).

Anyway, let’s cut to the chase, and let me clarify my (not at all original) views on the increasing resort to negotiated solutions (for previous posts on this see, among others, here, here or here).

I have mixed feelings about the use of Article 9 decisions. On the one hand, I understand the Commission’s tendency to resort to them. Commitments enable authorities with limited resources to swiftly and effectively address certain practices (particularly in rapidly evolving markets, where a level-playing feel is needed, or when a fine does not appear to be adequate). On the other hand, given my whining-lawyer nature (and because of the little academic wannabe that some of us have inside) I sometimes also regret the lack of discussion and precedent inherent to such decisions. Now, is this new commitment-based enforcement paradigm positive or negative? There’s no clear answer. I guess that it all comes down to the role one atributes to the Commission: is it to put and end to anticompetitive conduct and to restore competition immediately through direct intervention, indirectly through precedent setting, or through a careful balance of both?

Revolving doors (a contrarian view)

Nico and I have come up with a way of duplicating posts out of one piece of news; one of us writes something and then the other disagrees 😉

Last Tuesday Nico wrote a post titled “Revolving doors” in which he expresses the concern that “the cumulative effect of appointing previous Commission officials as judges, plus the very many référendaires who have spent some time in the EU administration may give rise to a pro-Commission bias at the Court“.

[I was actually in Luxembourg for a Court hearing when Nico wrote it, but I’ll tell you about that some other time].

Without entering into the debate on whether there is or there isn’t too much of a pro-Commission bias at the Court (in my view, there is the same deference towards the public authority that we find in any European administrative system – in the US, on the contrary, that deference is less visible-), I don’t at all share Nico’s concern.

Assuming that there was such bias, I would argue that it has nothing to do with former Commission officials becoming members of the Court:

Only two current Judges at the GC have previously worked at the Commission: Marc van der Woude (who was also a private practitioner, which should offset any bias; ask anyone in the business their opinion on him and you won’t hear a single negative one), and Guido Berardis (also an excellent and objective Judge).

This is 2 out of 27 (3 if the Committee gives the green light to Kreuschitz, which it undoubtedly should) does not appear to be an unreasonable proportion. Furthermore, all three of them were part of the Legal Service, which means that an important aspect of their work -aside from pleading- consisted in identifying flaws in the Commission’s work.

If you ask me (and part of my job is to beat the Commission in Court), the problem lies not in Judge’s previous professional experience, but rather in Judges being appointed for political reasons other than their knowledge of the law (see here). And people who know about EU law are generally -there are a few exceptions- either academics (most of whom also have defined pro or anti Commission biases), practitioners (we may have the opposite bias, plus we’re too competition law oriented), and Commission officials.

In sum, I would argue that we need Judges that know their stuff inside out, no matter their nationality or whether they are national judges, academics, ex-Commission officials or former practitioners.

Antitrust Writing Awards- The campaign begins

(Since this post is about awards, we thought a pic form last night’s grammys ceremony would be appropriate. I randomly came accross this one, but it risked being inappropriate, so we’ve decided to go for a more politically correct one).

You may remember that last year we ran a campaign (see here) for Nicolas to win one of Concurrence’s Antitrust Writing Awards, which he did for his paper on Credit Rating Agencies.

This year the Editorial Committee at Concurrences has shortlisted 3 pieces written by people who have contributed to this blog, so we thought we’d ask you to please take a minute to give them your 5-star vote 😉

The nominees are:

– On the category for Academic paper on Anticompetitive Practices: Pablo Ibañez Colomo (LSE), for Market Failures, Transaction Costs and Article 101(1) TFEU Case Law, You can read it and vote for it at: http://awards.concurrences.com/academic-articles-awards/article/market-failures-transaction-costs By the way, Pablo gave a lecture on this topic at the IEB in Madrid a few days ago; the slides are available here: Making sense of Article 101 TFEU

– On the category for Academic papers on Economics: Hans Zenger (CRA) for Loyalty Rebates and the Competitive Process : You can read it and vote for it at: http://awards.concurrences.com/academic-articles-awards/article/loyalty-rebates-and-the

– On the category for Business papers on Economics, myself, for Economics in competition law, You can read it and vote for it at (no need to read this one, you can skip it provided that you vote for it): http://awards.concurrences.com/business-articles-awards/article/economics-in-competition-law (actually, the nominated post does not rank among the ones I’m proudest of, but I’m nevertheless grateful for the nomination).

– We are told that Chillin’Competition has also been shortlisted as one of the top 30 professional publications that will be reviewed by Concurrence’s editorial board, which will then come up with a ranking (for more info, click here). You cannot vote for us here, but we’d be thankful if you could please exert any sort of coercion on the jury

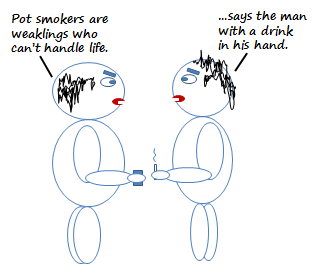

The ‘Tu Quoque’ Fallacy – Some more thoughts on Commission v Google

Heard at today’s GCLC lunch talk, seemingly in defense of Google’s search manipulation tactics: Bing is also linking preferentially to its own related services (maps, etc.). So the complainants, and Microsoft in the first place, should take a pass.

On further thoughts, this is a pretty weak argument.

First, the idea underpinning this argument seems to be that Google’s strategy is standard industry practice. And the upshot would be that Google’s conduct has a rational business justification. But the fact that a course of conduct is frequent within an industry, and that it has been replicated by rivals, does not make it presumably lawful. Many drivers breach the law by speeding everyday, yet this is no reason to hold their conduct lawful. Similarly, the fact that conduct is rational is not a cause of antitrust immunity. Collusion is often rational, yet it is strictly forbidden.

Second, this argument actually works in favour of Microsoft’s allegations. It is precisely because preferential placement of links on search engines has the ability to steal competitors’ market share – and in turn to foreclose – that Microsoft uses this strategy. But Microsoft does this to penetrate the market and/or avoid market marginalisation. And there’s no cause for concern here: given Bing’s very low market share, the preferential placement of links at best yields minor foreclosure effects. You may call this procompetitive foreclosure. In contrast, Google has a paramount market position. Hence its conduct is likely to exert anticompetitive foreclosure effects.

On the link between the magnitude of dominance and the intensity of anticompetitive effects, see §20 of the Guidance paper:

“in general, the higher the percentage of total sales in the relevant market affected by the conduct, the longer its duration, and the more regularly it has been applied, the greater is the likely foreclosure effect”

And on the fact that not all foreclure is unlawful, see §22 of the CJEU ruling in Post Danmark:

“not every exclusionary effect is necessarily detrimental to competition”

Finally, the argument surmises that competition law should treat market players equally. But in this industry, Google is seems dominant, Bing not. Those two firms are thus in distinct situations, and the argument again does not fly. It is indeed well settled that pursuant to Article 102 TFEU, dominant firms are subject to a “special responsibility” (whatever this means) possibly for the reason set out in my second point. Like it or not, competition law imposes higher constraints on dominant firms than on non-dominant firms.

The sole possible way to make sense of this argument boils down to a moral issue, best expressed in the maxim: “nemo auditur propriam turpitudinem allegans”. But it is well known that this argument has no traction in competition law, which has no moral content, a point forcefully made by Bork – a late pro-Google advocate – in his early Antitrust Paradox. And this, in any case, would not bar the Commission from taking over the investigation on its own motion.

Overall, by trying to counter argue that Bing also manipulates search results, Google is falling into the well-known Tu Quoque fallacy.

PS: the Lunch Talk was great. We heard two economists, Anne Perrot and Cedric Argenton, speaking very clearly to lawyers. We also watched a lawyer, Alfonso, morphing into a complete hi-tech geek. The introduction of his presentation was simply hilarious. I rarely laughed so much at a conference. The slides will appear on the blog very soon.

PS2: link to the above pic here.

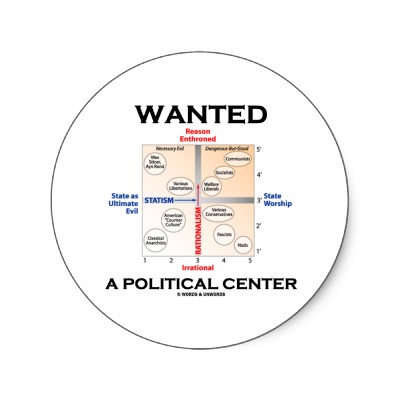

Antitrust and the political center

A few weeks ago I published a post called “Antitrust and political imbecility“. The raw ideas in it had been in my mind for a while, but conscious that I would likely not take the time to refine them, I chose to publish them on this blog with the hope that they would benefit from public discussion. I wasn’t particularly proud of this post, but Lindsay Mcsweeney (Competition Policy International) thought it was original and asked me to develop it for a special issue of CPI’s Antitrust Chronicle to be published right after Christmas. I accepted thinking that it would only take a few hours of my holidays; little did I know that I would break my arm and go through some pains to finish it! (btw, I’m back on track as of today). In any event, and thanks to Lindays’s pressure encouragement, it’s done.

Those interested in reading my take on why antitrust law can be regarded as sensible centrist economic policy can do so here. Non-CPI suscribers can read it here (courtersy of CPI): Antitrust and the political center-

Any critical feedback would be most welcome!

New paper

I just posted a new paper on ssrn. It is entitled “New Challenges for 21st Century Competition Authorities“. It is a short and modest paper, which builds on my presentation in Hong Kong a few months ago. Hereafter, the abstract:

This paper discusses challenges for competition authorities in the 21st century. Those challenges were identified on the basis of a statistical review of the articles published since January 2011 in five major antitrust law journals. The assumption underlying this literature review is that the topics that statistically attract the most the attention from contemporary antitrust scholars are those that will likely constitute the main challenges for 21st century competition authorities.