Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

#ChillinCompetitionFineArt (V)

Remember when I’ll said I would stop posting memes and find the time for something substantive? Well, this is Round 5… Click here for Round 1 , Round 2 , Round 3 and Round 4.

41.”Commission asks company to be open-minded in compliance negotiations”

42. “When you learn that your client was first in line for leniency”

43. “When you learn that your client was not first in line for leniency”

44. “When opposing counsel tries to attack my credibility“

45. “Cartel”

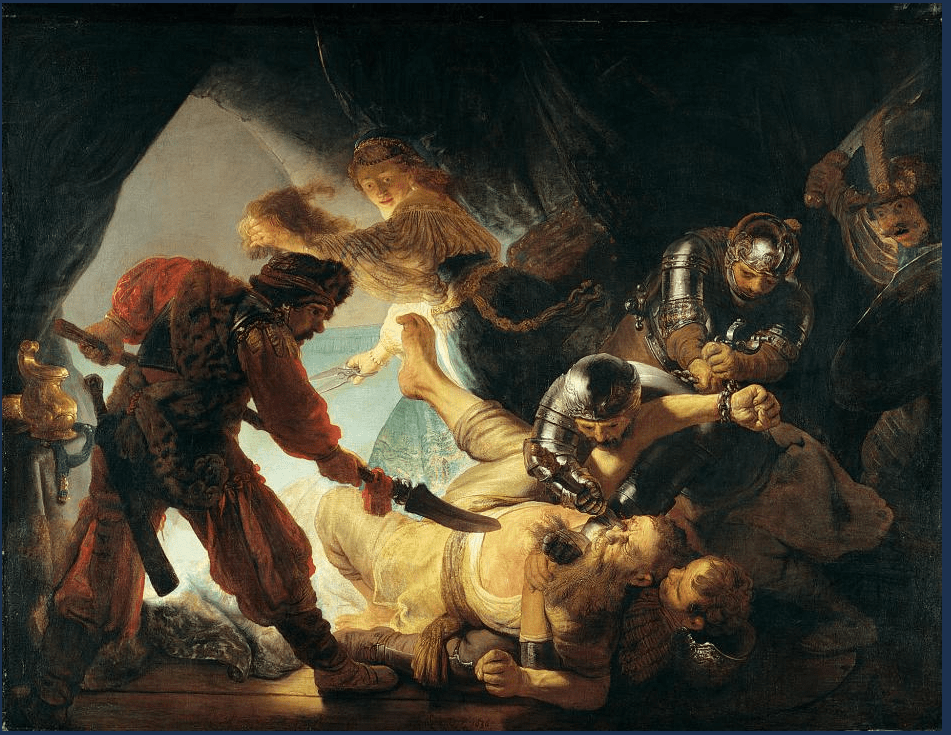

46. “Commission punishing a cartellist, with the whistleblower in the background”

47. “Reviewing Excel Sheets Prior to Merger Filing”

48. “The Chief Alchemist”

49. “When you learn what your partner makes”

50. “Body language while I listen to my opposing counsel in Court“.

51. “When I am deep in concentration and I don’t want people interrupting in my office”

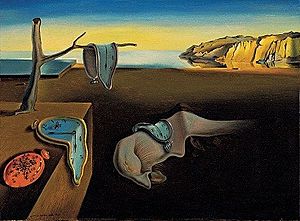

52. “Leniency Statement“.

53. “Co-conspirator takes the stand as your star witness”

54. “When the Judge says come see me in chambers”

On the CMA’s Ping case: objective justification and object restrictions under Article 101(1) TFEU

The Ping case was decided last year by the CMA. It has made the headlines again following the challenge brought against the decision. I (well, the two of us) have followed the case with a lot of interest and it is perhaps the time to say a word about it. Alfonso will address the procedural issues in the coming days.

On the face of it, the case may look straightforward from a substantive standpoint. It is about an absolute ban on online sales in the context of a selective distribution agreement. Following Pierre Fabre such a ban is in principle (that is, unless objectively justified) restrictive by object .

In Ping, the CMA concluded that the ban amounted to a ‘by object’ infringement that was indeed not objectively justified.

I find the route through which the CMA reached its conclusion problematic. If I do not take issue with the conclusion as such, I believe the legal analysis conducted by the authority departs from the principles laid down in the case law.

When establishing whether an agreement is restrictive by object, the bar set by the CMA is too high and (more importantly) unprecedented. The relevant judgments suggest that the legal test applied by the Court of Justice to draw the line between object and effect restrictions differs from the one applied in Ping.

Pierre Fabre and restrictions by object

The Court held the following in para 39 of Pierre Fabre:

‘As regards agreements constituting a selective distribution system, the Court has already stated that such agreements necessarily affect competition in the common market (Case 107/82 AEG‑Telefunken v Commission [1983] ECR 3151, paragraph 33). Such agreements are to be considered, in the absence of objective justification, as “restrictions by object”‘.

What does the Court mean by the above? As I have written many times before, this paragraph makes a very sensible point. In my view, it is just a way of expressing what the Court has traditionally done to distinguish between object and effect restrictions.

Readers of this blog are already familiar with the case law that captures the Court’s approach to the object/effect divide. The more explicit rulings about this approach include Metro I, Pronuptia, Delimitis, Asnef-Equifax and Cartes Bancaires.

In all of these cases, the inquiry is crystal clear: every time, the judgment starts by ascertaining whether a given clause serves a legitimate aim (that is, whether it is a plausible means to attain a pro-competitive objective).

The plausible bit is the important one. It means that the bar in the case law is low. Nowhere does the Court suggest or imply that the inquiry is an in-depth one.

In particular, nowhere does the Court suggest or hold that an agreement is restrictive by object if there are less restrictive means to attain the legitimate aim sought by the parties.

If you take a look at the above cases you will realise that the Court has never examined whether there were, in fact, other ways to attain the legitimate aims sought by the parties. This question appears to be irrelevant when establishing whether an agreement is restrictive by object.

- In paras 10-12 of Delimitis, for instance, the Court identifies the legitimate aims served by an exclusive dealing agreement. Are there less restrictive means to achieve the same objectives? Well, we know that rebate schemes can serve the same purposes, and they are certainly less restrictive than an outright exclusivity obligation. But the Court, when examining whether such an obligation is restrictive by object, did not find it relevant or necessary to consider whether the aims ought by the parties could be achieved through other, less restrictive, means.

- Consider nowPronuptia. In paras 15-17 of the judgment, the Court identifies the legitimate aims pursued by franchisors. Can one think of less restrictive means to attain the same objectives? Sure. Selective distribution is one example that comes to mind immediately. Again, the question of whether the franchisor could have protected its know-how and reputation through less restrictive means was deemed irrelevant when identifying the object of the agreement.

The mismatch between the legal question and the legal test in Ping

The test set out in Ping is different. According to the CMA, a clause is objectively justified (and thus escapes the qualification as a ‘by object’ infringement) if it can be shown that there are no less restrictive means to attain the legitimate aim.

The CMA applies, in other words, a necessity test, as opposed to the plausibility test endorsed by the Court in Luxembourg. In case you were wondering: there is nothing in Pierre Fabre that suggests this question should be subject to a less-restrictive-means test. The CMA derives it from domestic case law.

The impression I get from the decision is that the CMA conflates two separate questions: that of whether a clause is objectively necessary and that of whether it is restrictive by object.

As a result of this conflation, there is a mismatch between the legal question considered in Ping (is the ban restrictive by object?) and the legal test applied (is the ban necessary?).

The objective necessity test laid down by the CMA plays an important role in Article 101(1) TFEU. But its role is not to determine whether a clause is restrictive by object.

If it appears that a clause is objectively necessary, the said clause is not restrictive at all, whether by object or effect. It is prima facie lawful. When the (stricter) objective necessity test is met, the clause falls outside the scope of Article 101(1) TFEU altogether, and it is not even necessary to establish its effects.

The CMA conflated the two tests, I believe, because selective distribution systems are presumptively lawful if certain conditions (defined in para 41 of Pierre Fabre) are fulfilled. When these (i.e. the Metro I criteria) are met, the clauses are deemed objectively necessary and are not caught by Article 101(1) TFEU at all.

What if a clause is not objectively necessary?

Even if you agree with the above, you may still have a couple of reasonable questions: what does the third condition of Metro I (proportionality) mean? In the same vein, you may ask what happens when a clause does not meet the objective necessity test.

If you read beyond Pierre Fabre (if you read, in particular, the 1980 Perfumes judgments, including Lancôme, and Pronuptia) you will be able to get the answer to the two questions.

The proportionality assessment in Metro I (and Pronuptia) is essentially about whether there is a link between a given clause and the legitimate aim that is being considered. If no such link exists, the clause will be deemed to go beyond what is necessary to attain the aim in question. As a result, it would also fail the objective necessity test.

In Pronuptia, for instance, the Court took the view that there is no link between the legitimate aims sought by franchising agreements (protection of the know-how and reputation/uniformity of the system) and territorial restrictions protecting individual franchisees.

In the context of selective distribution, the Court ruled early on that there is no link between quantitative restrictions and the aims sought by this business model.

Importantly, the fact that a clause does not satisfy the objective necessity test does not mean that it is restrictive by object.

Paras 21-24 of Lancôme illustrate this point very well. A clause may fail the objective necessity test in relation to one legitimate aim, but may be a plausible means to attain another one (and thus may be subject to an analysis of effects). In fact, Lancôme refers explicitly to Société Technique Minière and to the need to consider the effects of clauses that do not meet the Metro I conditions.

Ping suggests that there no shades of grey in the context of Article 101(1) TFEU. A clause is either restrictive by object or necessary and thus lawful.

This understanding of the provision is at odds with the case law. Contrary to what the decision suggests (and this is perhaps its main weakness), a clause that fails the objective necessity test is not always (or not necessarily) restrictive by object. If the clause in question is a plausible means to attain a legitimate aim, it will be subject to an effects analysis.

Just think of Delimitis: the Court never suggested that exclusive dealing is objectively necessary. However, it ruled that it is not restrictive by object. Cartes Bancaires is another wonderful example.

Judicial review and Article 102 TFEU: undue deference to the Commission? Not so fast

One of the most popular mantras in the EU competition law community is the idea that the Commission ‘always wins’ Article 102 TFEU cases, and that it is all but impossible to see an abuse decision annulled before the EU courts.

I have spent quite a bit of time examining this question (and related ones) lately. I have concluded that there is perhaps a grain of truth in this mantra. As often happens, however, the grain of truth has been distorted so much that it is barely recognisable. Even worse, most claims these days are made without much evidence to back them up.

What do the figures tell us when we look at them?

If you look at the figures about which most people care (challenges brought against Article 102 TFEU decisions and rate of annulment of these decisions) you are likely to be surprised.

You will realise that seeing a Commission decision annulled was actually quite commonplace in the early years (that is, until the late 1980s); much more so, in fact, than conventional wisdom would suggest.

Then, something happened when the General Court was created. It is true that the annulment of Commission decisions became significantly less frequent at the time. This is certainly the origin of the mantra, and the underlying (and possibly only) grain of truth of some narratives.

However, these figures do not mean, in and of themselves, that the EU courts became unduly deferential to the Commission, or that its attitude to judicial review of abuse cases changed. This is the point at which we enter the realm of speculation.

What do the figures fail to tell us?

I keep insisting on this point, but I do not think I can emphasise it enough: the annulment of a Commission decision may be a popular proxy for curial deference, but it is actually a very poor one. The fact that a decision is annulled, or fails to be annulled, does not say anything about the intensity of judicial review.

Why is it that annulments fell when the General Court was created?

The undue deference story is only one possible explanation of the phenomenon. The observed shift in the rate of annulments is also consistent a scenario in which the authority became increasingly risk averse and its decisions became subject to tight scrutiny by the review courts – I am not saying this is what happened, it is just that it is also perfectly plausible.

In fact, if the early years were marked by frequent annulments in Article 102 TFEU cases, it would be reasonable for the Commission to become more risk averse over time, and to pursue only the cases that it is certain to win. With risk aversion, annulments inevitably become less frequent, even if judicial scrutiny is as intense as it can get.

Conversely (and equally importantly), the frequent annulment of Commission decisions is not evidence, in and of itself, that judicial review is intense. Many of the biggest victories for the authority originated in decisions that were annulled.

Just think of Kali & Salz: the individual decision may well have been annulled, but the Commission won on a major issue of principle (what matters for a repeat player): collective dominance was found to fall under the scope of the Merger Regulation.

Bottom-line

The bottom-line of the above is clear: examining the substance of individual decisions is inevitable if one wants to come to meaningful conclusions about whether the annulment (or the absence thereof) is a reliable proxy for deference to the analysis of the Commission.

In particular, it is necessary to develop a way of checking whether the Commission is risk-prone or risk-averse when adopting Article 102 TFEU decisions. This is one question that has kept me nicely busy. Answers? Soon! But I can say that the truth, as far as I can tell, is (surprise, surprise) complex and does not quite fit one particular story or narrative.

The pace of the law

I was thinking, while drafting this post, that some of those who claim that the EU courts are unduly deferential are just impossibly impatient people. These people would like to see the complete overhaul of the EU competition law system from one day to another.

This is not how the law works, and for good reasons. The pace of the law is – and can only be – slow and incremental. It is a mistake to think that courts are deferential simply because their attitude towards legal change takes into account factors beyond the specific case at hand. Predictability and stability also matter.

Legal change may seem slow; eppur si muove: just think of Intel.

And as I write this, I am reminded of the excellent Rebecca Haw Allensworth, who has written (much more) eloquently about these questions. You may want to take a look, for instance, at this paper.

22 May Brussels combo: 100th (!) GCLC Lunch Talk and ASCOLA/ACE/UCL event on sponsored research

The Global Competition Law Centre will hit a significant milestone on 22 May: 100 (!) lunch talks. And for some of us it feels like yesterday when the first one was announced…

To mark the occasion, the event, devoted to Brexit and its implications for EU Competition, will be a tad longer than usual. It will feature an opening address by Luis Romero Requena (Director General of the Legal Service at the Commission), a keynote speech by Margaritis Schinas (Chief Spokesperson at the European Commission) and some closing remaks by Judge Ian Forrester QC (General Court).

I am honoured to have been invited to take part in the second panel, which will address the tricky issue of State aid control post-Brexit

More info on the event (to take place at The Hotel), and on how to register, can be found here.

The GCLC lunch talk will be over at around 4pm. An hour later, at the Solvay Brussels School Economics & Management, an event on corporate (and other) sponsorship of academic research will kick off. It is organised by Ioannis Lianos, who has been working on a code of conduct for the members of the Academic Society of Competition Law (ASCOLA).

The event, which is great news for the EU competition law community, is jointly hosted by ASCOLA, the Association of Competition Economists and UCL. In addition to Ioannis Lianos and yours truly, confirmed speakers include Damien Geradin, Penelope Papandropoulos, Alexis Walckiers and Wouter Wils.

More info here.

5 Reasons to Register To…. (clickbait)

5 reasons why you should register to the upcoming module on EU Competition Procedure at the Brussels School of Competition. Click here for more info and to register.

1. Unless you are a student at the College of Europe (in which case I’m sorry that you also had to suffer through my guest lectures and the case study featuring Pablo and his tax returns), there is no other place where you can discuss in detail every aspect of competition procedure. This is the stuff that very often determines the outcomes of cases and, if you come, you will realize it is fun too.

2. What else would you rather be doing on the afternoons of Friday 18 May, 25 May and 1 June?

3. In 3 intensive 5-hour sessions you will be privy to the inner-workings of competition cases, to case-winning ideas and to a formidable syllabus that you will never have time to read.

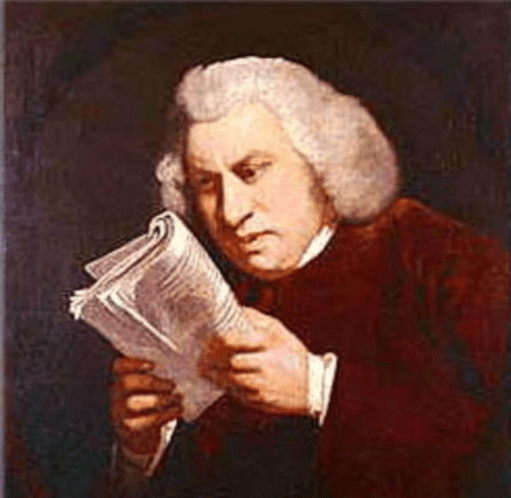

4. You will receive a lecture from the handsome man depicted above. And he may perhaps invite you to a round of beers afterwards* (*Disclaimer: Offer Conditional on Evaluation Form).

5. The upcoming module at the Brussels School of Competition has recently been awarded the Chillin’Competition prize as the “Best Module on Procedure at the Brussels School of Competition“. My co-lecturers Nicholas Khan QC (EC Legal Service) and Konstantin Jörgens (Garrigues) are also respectively ranked as the “Best Public Official Teaching in the Procedural Module” and as the “Top-German Lawyer Teaching in the Procedural Module“. I myself have been listed as “Leading Under 36 Above 34 Lecturer on Procedure” and “Lecturer to watch” 😉

P.S. The description above should probably receive a Chillin’Competition Writing Award for “Best Description of a Competition Law Module on Procedure at the BSC“.

#ChillinCompetitionFineArt (IV)

And to finish off this is Round 4. Click here for Round 1 , Round 2 and Round 3. If you have any favorites, please let us know in the comments to this post.

A confession: this was initially conceived as a way to maintain my contribution to the blog during weeks when I didn’t have time to write anything serious. The success in terms of visits and contributions (sorry that we didn’t publish them all) suggests that I should abandon writing altogether and come up with more memes instead…

31. “Before and after commitments”

32.”Look son, we will notify in Zimbabwe”

33.”Hipster Antitrust”

34.”Searching for Market definition in Google Shopping”

35. “Cute, they think rules provide legal certainty” (inspired by Pablo’s post from yesterday)

36. “Fairness as a legal standard”

37. “When the Commission reads out the incriminating evidence against your client”

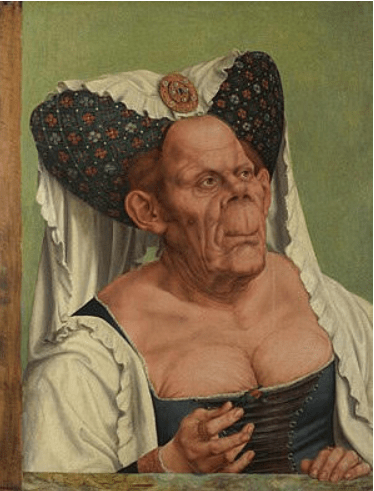

39. “Reading how the Decision summarized his arguments”

40.”And then the economist said: “If you look closely, he wasn’t as efficient”

Why rules do not always give legal certainty – and why they are not necessarily administrable

Rules are very popular in competition law these days. We need them, many like to claim, because we need clarity and legal certainty. At the end of the day, stakeholders should know where they stand, and nothing can beat a rule that states that X is allowed or prohibited full stop – no effects analysis, no balancing and no further questions asked.

Sometimes these claims are sweet. Occasionally they are made as if the rest of the world had been missing the obvious all along. The truth is that we are all aware of the advantages of rules. What is more, I am yet to meet someone who is against clarity, legal certainty and administrability – I, for one, am a great fan of all three. It is just that, as it often happens, things are a bit more complicated.

The point of this post is not so much to explain why rules (as opposed to standards) are not always desirable, or ideal, in competition law.

My idea is to challenge the belief that rules necessarily provide legal certainty and are administrable. Sometimes, rules can be opaque and all but impossible to apply and anticipate in practice. In fact, the case law and the administrative practice of the Commission provide several valuable examples in this sense.

When people claim that rules are clear and administrable, they typically focus on the outcome of the rule. The rule determines ex ante whether a given practice is authorised or prohibited. There is no need to show, ex post or on a case-by-case basis, whether the practice has an effect on competition.

As far as the above is concerned, those in favour of rules are right. The problem is that the discussion misses the other component of the rule. When we ask the question of whether a rule provides clarity and administrability, we need to pay attention not only to the outcome but also to the scope of the rule (or trigger, to use Schlag’s expression).

In other words: even if the outcome of the rule is clear by design, we need to ask whether the scope of the rule is clear too, or whether there is uncertainty about how broad it is and about the range of conduct that is subject to it.

Legal uncertainty is inevitable when we do not know for sure the behaviour that is subject to the rule (in other words, when the trigger is ‘soft’, as Schlag would put it). In such circumstances, the much-touted advantages of rules are wholly absent.

Let me give you a couple of examples.

In Hoffmann-La Roche, the Court defined a prohibition rule with a clear scope: rebates conditional upon exclusivity or quasi-exclusivity. It was, in other words, a rule with a hard trigger.

As the case law evolved, the trigger softened, and the rule became progressively much less clear and predictable. The scope of the rule first expanded in Michelin I. After that case, it covered rebates having the same effects as those conditional on exclusivity or quasi-exclusivity. Something reasonable, may I point out.

With Michelin II, the rule expanded further. This is the point at which it softened beyond recognition. In Michelin II, the Commission successfully pushed the boundaries of the prohibition rule to cover all rebates with a ‘loyalty-inducing’ effect.

Take a look at that case, and British Airways. The ‘all the circumstances’ test laid down in them is impossible to administer. How long is a long reference period? Are all retroactive rebates prohibited in reality? What if the rebate is transparent and communicated in writing to customers? What if the rebate is standardised? What if the coverage is limited? Good luck figuring out how these factors are balanced against one another.

No wonder the Commission reviewed its approach to the enforcement of Article 102 TFEU after Michelin II.

The AKZO test laid down by the Court has a clear scope. It is based on a well-crafted, hard trigger: if a dominant firm prices below average variable costs, it infringes Article 102 TFEU. The same is true if prices fall below average total costs and there is evidence of an anticompetitive strategy.

What people forget is that the Commission, in the original AKZO decision, defended a rule with a much softer trigger. So soft, in fact, that it was impossible to administer. The Commission argued that a cost-based test was not necessary to establish the abusive nature of predatory pricing.

According to the decision, aggressive pricing by dominant firms would be prohibited full stop (the outcome, in other words, was clear).

However, the question of whether a practice amounts to aggressive or predatory pricing (i.e. the scope of the rule) in a concrete case would be evaluated, pursuant to this test, in light of a range of factors that may or may not be relevant in others. Take a look at the factors in the decision: impossible to anticipate whether a dominant firm is in breach of Article 102 TFEU, right?

As it often happens, the Court understood the implications of the rule laid down by the Commission in AKZO and hardened the trigger. This is perhaps the reason why the rule has not been altered fundamentally in the Guidance – and why the test has proved to be so popular.

Is there a moral in this story? I can think of the following:

- First, the debate about the design of legal tests in competition law should move beyond cliches and slogans. It is untrue that rules are always clear and administrable (if they are well designed, they are, to be sure). It is also untrue that standards (i.e. a case-by-case effects analysis) are necessarily opaque, convoluted and econometricky.

- Second (and on a related point), when some people defend the use of prohibition rules, they are being disingenuous. Some support rules not because of clarity and administrability, but because it is a powerful trick to shift the burden of proof.

E-commerce after Coty: my presentation at the ULB

I was really pleased that Denis Waelbroeck invited me to speak in the context of the legendary mardis du droit de la concurrence. I was there last week. It was a wonderful occasion to share my thoughts on Coty, the future of selective distribution and, more generally, of enforcement in the area of e-commerce.

Chaired by Denis himself and by Jean-François Bellis, the seminar was great. You can find my slides here (they are in English, don’t feel intimidated by the French used in the series!).

I felt it is the right time to discuss the online aspects of selective distribution. On the one hand, a consensus seems to be emerging about what was held in Coty. On the other hand, there are still some open issues that will have to be addressed (and will no doubt give rise to further legal frictions).

The consensus around Coty (and the recent Commission brief)

The issue of online selective distribution was, understandably, controversial before Coty. There is now a core set of principles around which a consensus seems to have emerged:

- The protection of the luxury image of a product can justify the setting up of a selective distribution system that complies with the principles set out in Metro I.

- Accordingly, a selective distribution system that aims at protecting the luxury image of a product is, under certain conditions, presumptively lawful under Article 101(1) TFEU.

- In Coty, a ban on the use of online marketplaces was deemed to be appropriate and proportionate within the meaning of Metro I.

- An online marketplace ban is not a ‘hardcore restraint’ within the meaning of Article 4 of the Vertical Block Exemption Regulation. According to the Court, such a ban does not restrict the territory into which, or the customers to which, retailers may sell their products.

- As a logical consequence of the above, an online marketplace ban can benefit from the Block Exemption Regulation irrespective of the nature of the product (luxury or non-luxury). The Commission has unambiguously endorsed the consensus on this point in a recent brief specifically devoted to Coty.

E-commerce after Coty: what to expect?

Brand image beyond luxury

An important pending issue, which I addressed at length during the seminar, concerns the legal treatment of selective distribution systems that are aimed at protecting the brand image of a non-luxury product. Are such systems restrictive of competition by object?

I do not think they are, for the simple reason that the object – the purpose, the rationale – of such systems is identical to the object of distribution networks relating to luxury products. In other words: the preservation of an aura of luxury is not the only reason why a manufacturer may be interested in preserving its brand image.

It is reasonable to say that Asics or Mizuno shoes are not luxury products. This fact does not mean that brand image is not important for a manufacturer of running shoes. Amateur athletes are keen to buy products that are safe, reliable and – above all – that prevent injury. How can one argue that a system that seeks to convey this information to end-users has as its object the restriction of competition?

It is useful also to think of Apple products – I often use the example of Apple premium resellers in class.

Apple’s immense success (and the resulting benefit for consumers and competition) is to a large extent due to its ability to ensure that end-users associate its brand with reliability, innovation and user-friendliness. Can one reasonably argue that a distribution system aimed at ensuring that this image is preserved is restrictive by object?

I emphasised in the seminar that none of the above is new. In fact, the Court of Justice has long understood the importance of preserving intangible property in the context of Article 101(1) TFEU. In Pronuptia, the Court held that clauses aimed at preserving the reputation and uniformity of a distribution network are not contrary to Article 101(1) TFEU. I fail to see how it can come to a different conclusion in relation to selective distribution.

In this regard, I also provided an economic perspective – it sometimes helps!

Many miss the fundamental point in this regard: by restricting the use of online marketplaces, manufacturers do something that looks prima facie irrational.

Why would a supplier reduce the exposure of its resellers and thus the possibility of selling more? Experience shows that, whenever we see a firm doing something that appears to go against its interests, the practice most probably has a pro-competitive object. Selective distribution is not different in this sense. As in other areas, the Court’s intuitions are aligned with mainstream economics.

Next steps

The developments that have followed Coty suggest that, again, a divide has emerged between Germany and other Member States. While courts in France and the Netherlands have embraced consensus positions in relation to the judgment and its implications, German courts (and the Bundeskartellamt) are clearly less inclined to read anything in Coty that goes beyond its narrow factual circumstances.

Ongoing disagreements relate, inter alia, to two points: one relates to the application of Coty beyond luxury products, already discussed, and the second to the treatment of other clauses having a similar object and effect – such as a ban on the use of price comparison websites. I explained that the disagreement may very well reach the Court again.

Keeping perspective

There is something fascinating about the application of competition law in online markets. I often have the impression that, for some reason, principles that have been with us for decades tend to be forgotten when things ‘get digital’. As I said, we keep ‘rediscovering mediterraneans’ these days.

I ended my lecture identifying a few guiding principles when thinking about competition law in the online world:

- Price is not the only important parameter of competition. A practice may significantly limit price competition and still be presumptively legal under Article 101(1) TFEU. This principle has been with us since the late 1970s. The Court made it explicit in Metro I and Metro II (in particular the latter). Competition in many digital and high-tech markets is not about prices anymore – think again about Apple’s immense success!

- These are the best of times for intra-brand competition: when we read about online distribution, we sometimes get the impression that it is in crisis, or in need of a boost. The reality is that independent retailers have never had it so good.

- Competition policy should be consistent: I struggle to see how a competition authority can simultaneously warn against the power of online platforms and at the same time develop policies subsidising these same platforms (such as a policy favouring the use of online marketplaces). Consistency, and thinking about the unintended consequences of some measures, could take us a long way.

#ChillinCompetitionFineArt (III)

And this is round 3! Click here for Round 1 and here for Round 2.

***

23.”When your boss makes a terrible joke but you want a promotion” *

(Authored by a soon-to-be-former Garrigues associate after seeing one of my memes)

24.”Definitely the final deadline!”

25.”Commission RFI generates 100,000 responses”

26.”On the way to the oral hearing”

27.”On the way back from the oral hearing”

28.”Entering the office after a Court victory”

29.”A dawn raid?? To the shredders!!!“

30.”Horizontal Overlap”

Case C-525/16, Meo – Serviços de Comunicações e Multimédia: a major contribution to Article 102 TFEU case law

Love them or hate them, the EU competition law community should be grateful to collecting societies. Their activities have ensured a steady supply of preliminary references since the very early days. It looks like things are unlikely to change soon.

Yesterday’s judgment in Meo is the latest – but will certainly not be the last – of these preliminary rulings. The case concerned a relatively narrow issue: the interpretation of Article 102(c) TFEU in the context of exploitative discrimination.

You certainly remember that Article 102(c) TFEU concerns the application of ‘dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions’ by dominant firms. According to the letter of the Treaty, the prohibition applies only insofar as it places some firms ‘at a competitive disadvantage’.

Reasonably – and as expected – the Court has held in Meo that the ‘competitive disadvantage’ cannot simply be assumed, or taken as a self-evident consequence of the behaviour of the dominant firm. Effects in this sense will have to be established on a case-by-case basis.

In any event, the contribution of Meo to the case law goes well beyond the legal status of exploitative discrimination. The Court has clarified some fundamental questions about which we lack meaningful guidance.

Not every disadvantage amounts to an anticompetitive effect: In para 26 of the judgment, the Court holds that ‘the mere presence of an immediate disadvantage affecting operators who were charged more, compared with the tariffs applied to their competitors for an equivalent service, does not, however, mean that competition is distorted or is capable of being distorted’.

Simply put: the Court clarifies that not every disadvantage resulting from the behaviour of a dominant firm amounts to an anticompetitive effect within the meaning of Article 102 TFEU. This clarification is no less than crucial, both in the context of exclusionary and exploitative practices.

The Court has put to rest, for good, the idea that practices (any practice) by a dominant firm cannot fail to have anticompetitive effects. According to this interpretation, anything that makes rivals’ or customers’ life more difficult would be abusive. Post Danmark I already dismissed this interpretation of Article 102 TFEU; Meo is the last nail in the coffin.

This is a point that Alfonso and I already emphasised in our piece on the notion of restriction of competition. A restrictive effect cannot be everything, it only exists when a practice harms firms’ ability and incentive to compete.

There is no de minimis threshold under Article 102 TFEU, true. However, not every practice has an effect: In Post Danmark II, the Court held that there is no such thing as a de minimis threshold below which anticompetitive effects can be excluded under Article 102 TFEU.

Some people interpreted this point as meaning that, since there is no de minimis in Article 102 TFEU, any practice has an anticompetitive effect. The Court dismisses this view. What Post Danmark II means, Meo explains, is that, because we are dealing with a dominant firm, exclusionary effects cannot be ruled out ex ante. However, these effects will still need to be established in concreto.

As the Court puts it in para 29 of the judgment: ‘[…] in order for it to be capable of creating a competitive disadvantage, the price discrimination referred to in subparagraph (c) of the second paragraph of Article 102 TFEU must affect the interests of the operator which was charged higher tariffs compared with its competitors’.

Final thoughts: The case law makes more sense after Meo. The analysis of effects is a meaningful one under Article 102 TFEU, as it is under Article 101 TFEU and merger control. Crucially, some of the issues it addresses will, before too long, be addressed by the EU courts.